In-Depth: Philippe Dufour Grande Sonnerie Pocket Watch No. 1

The most significant?

A quartet representing the entirety of Philippe Dufour’s repertoire went under the hammer last year, with the Grande Sonnerie wristwatch no. 1 setting the record for any Dufour sold publicly when it achieved the equivalent of US$5.2 million including fees.

Sold at the same auction, but for substantially less, was the Grande Sonnerie pocket watch no. 1. Despite the relative values, the pocket watch is arguably a more significant timepiece within Mr Dufour’s work.

Why?

Initial thoughts

In today’s wristwatch-centric era, the fact that it is a pocket watch counts against it. That was also the verdict of the market – the pocket watch sold for half as much as the wristwatch in November 2021.

But the Grande Sonnerie pocket watch is the ultimate distillation of Philippe Dufour’s philosophy, the ideal synthesis of the inspiration and impetus behind his creations.

He has long stated, both publicly and to me in past conversations, that his watches are a reverential homage to the haute horlogerie produced in the Vallée de Joux during its heyday before the Quartz Crisis, the period between the late 19th to the mid 20th centuries. Timepieces of that era, especially those with ebauches made by the valley’s best specialists like Louis-Elisee Piguet and Ami LeCoutre, are the best watches ever made in Switzerland in his view.

And the Grande Sonnerie pocket watch can pass for a timepiece from the late 19th century, perhaps even one made by Mr Dufour’s favourite historical watchmakers. Yet the Grande Sonnerie pocket watch is not exactly a remake – it exceeds its historical inspiration in the finest of details.

Mr Dufour’s work is superior to that of his forebears, slightly but surely more refined, as is expected from a lifelong obsession with the craft. There is an echo of the distinctly Japanese appreciation of craft in his approach of reproducing a fine historical object – but executing it at an even higher level that surpasses the original.

And the Grande Sonnerie pocket watch arguably succeeds better at its purpose than Mr Dufour’s Grande Sonnerie wristwatch. Almost exactly the same but executed with more finesse, the pocket watch is a perfect tribute to turn-of-the-19th century watchmaking. The wristwatch, on the other hand, is a miniaturised version of the same, when a wristwatch should instead contain more innovation.

The Grande Sonnerie wristwatch (left), and pocket watch

Still, the Grande Sonnerie is not about imagination or ingenuity, but unadulterated craft and traditional execution. By that benchmark it is perfection. And also by that benchmark it is the truest realisation of Mr Dufour’s ideals.

His later wristwatches were created because collectors increasingly wanted wristwatches; the heyday of pocket watch collecting was during the years Mr Dufour spent as a restorer. The Grande Sonnerie wristwatch is a landmark in being the first ever grande sonnerie wristwatch, but it is essentially a miniaturised version of the pocket watch. It is impressive, but the pocket watch feels more pure.

From left: Grande Sonnerie wristwatch, Simplicity, Duality, and Grande Sonnerie pocket watch

And then there’s his recent Anniversary Simplicity series, which feels like a project conceived solely to satisfy popular demand. In contrast, the Grand Sonnerie pocket watch sits removed from the currents of taste and fashion.

Both objet d’art and timekeeper, the Grande Sonnerie pocket watch is that reverential homage to the past accomplishments of the Vallée de Joux, very much a timepiece that Piguet and LeCoultre would have recognised and applauded.

A pair of winding click springs that can only mean one thing – grande sonnerie

The road through Le Brassus

Mr Dufour’s path to the Grande Sonnerie pocket watch is well known, having been told many times in interviews and recounted to me in the past. The outline is well known: his career started in 1967 at Jaeger-LeCoultre, where he was an expatriate watchmaker posted to Germany, the United Kingdom, and even as far as the United States Virgin Islands. After he returned to Switzerland in 1974, Mr Dufour spent time at Gerald Genta and then Audemars Piguet.

He then spent most of the 1970s doing restoration of vintage timepieces – mostly pocket watches, the primary genre of collecting of the period – often for Galerie d’Horlogerie Ancienne, which would later evolve into Antiquorum. It was during the that he realised majority of the watches he worked on, whether they were made in Switzerland, Germany, or even England, either originated as ebauches from the Vallée de Joux, or utilised complications made in the Vallée de Joux. The Vallée, in other words, was the source of all that was great and good in horology.

So in 1978 Mr Dufour established his own workshop. Any time not spent on restoration was dedicated to building the grande sonnerie pocket watch movement. Once complete – and housed in a brass case for lack of funds to buy a gold case – he hoped to find a brand who would bankroll serial production of the watch.

Audemars Piguet turned out to be that brand and placed an order for five watches. Mr Dufour completed the first watch in 1982 and the last in 1988. Mr Dufour delivered each watch in its entirety, including obtaining the cases and enamel dials from suppliers, a task that took some 2,000 hours per watch.

A Grande Sonnerie pocket watch with a sapphire dial made by Philippe Dufour for Audemars Piguet in 1987, which is now in the Audemars Piguet Heritage Collection. Image – Audemars Piguet

But not long after, one watch was returned to Mr Dufour by Audemars Piguet. As he tells it, the watch was transported to and from an exhibition alongside other watches in a container but unprotected, resulting in substantial damage. He fixed the watch and returned it to Audemars Piguet.

Then came the final straw: another of the watches had been carried to another exhibition by an Audemars Piguet employee in his jacket pocket, jangling around with his keys and lighter. And then his jacket got caught in-between the frame and door of his car – and he slammed the door on the watch.

Even though Mr Dufour recounted this to me some 30 years after it happened, his eyes still betrayed an inner fury at the disrespect shown to the timepiece and his 2,000 hours of work. He sent Audemars Piguet packing and swore never again to make a watch for someone else.

While the Audemars Piguet pocket watches are the first-ever examples of Mr Dufour’s work – and important for that reason – their stature is clouded by that history. As a result, the Grande Sonnerie pocket watch no. 1, which has his name on the dial, takes precedence in the Dufour hierarchy.

Twin-train masterpiece

Mr Dufour once remarked to me that the inspiration for the Grande Sonnerie movement was a calibre made by Reymond Freres. Founded in 1901 by the brothers John and Charles Reymond, the firm was based in Les Bioux, a town just 10 minutes from where Mr Dufour now lives.

Then in 1910, the brothers expanded their business by taking over the premises of the struggling Val-de-Joux Watch Co. Under the leadership of John’s sons, the business evolved into Valjoux, a leader supplier of ebauches, particularly chronographs. The subsequent tale is well known: Valjoux eventually became part of what is now known as ETA.

The Grande Sonnerie pocket watch

Though Mr Dufour had a specific historical basis for his Grande Sonnerie movement, it is still very much typical of a high-end clockwatch from the decades around 1900.

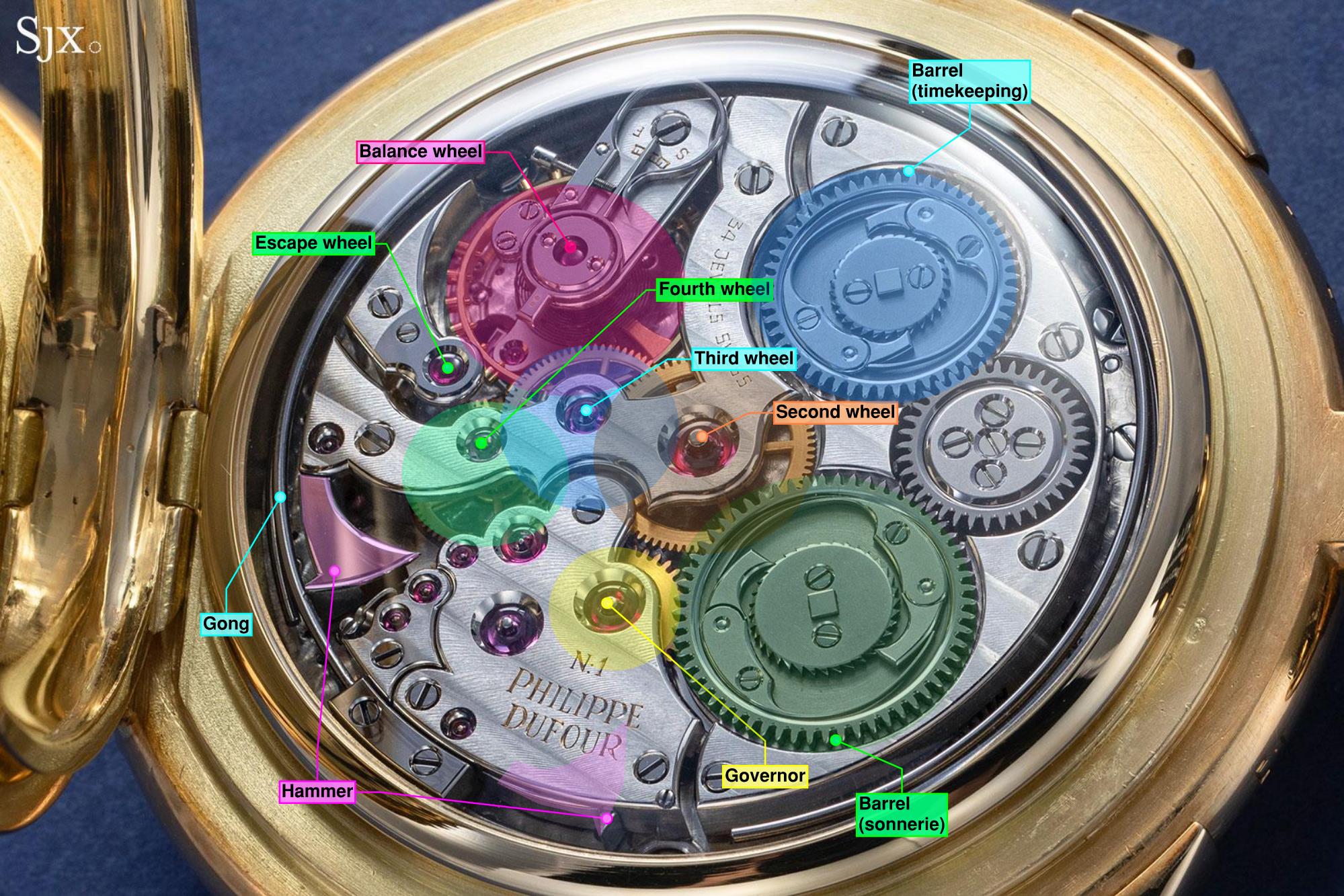

Eminently traditional in every respect, the movement is dominated by five bridges that each secure the barrels, going train, governor, balance, and escape wheel. This was, and still is, the de facto layout for a two-train, “grand” and “small” strike watch.

Figure 1: All of the key moving parts in the Grande Sonnerie pocket watch

Look at a Patek Philippe grande sonnerie pocket watch from the early 20th century and the resemblance is instantly obvious. And even a century later the fundamentals continue to be the same.

In an entirely modern grande sonnerie, namely the movement inside the Patek Philippe ref. 6301P, the similarity in layout slowly becomes obvious if you look hard enough.

A Patek Philippe Grande Sonnerie pocket watch with a movement completed in 1915

The GS 36-750 PS IRM inside the ref. 6301P, with the view dominated by a huge bridge for both barrels

That said, while the movement of the ref. 6301P operates on the same basic principles as a 19th century grande sonnerie, the movement is clearly conceived to make full use of contemporary materials and production methods, as well as advances in design. As a result, the calibre incorporates features like a full balance bridge as well as silicon components (that are hidden within).

The basics of the Dufour Grande Sonnerie pocket watch, or any other classical clockwatch, are straightforward. The movement contains twin barrels: one powers the timekeeping function and the other the grande et petite sonnerie. Turning the crown in either direction winds one of the two barrels thanks to the crown wheel and winding clicks.

The twin barrels, each with its own pair of winding clicks to stop the barrel from going backwards when the other is being wound

Because the sonnerie strikes the time en passant, or as it passes, its constant and regular operation requires a tremendous amount of energy, enough that it needs a power source independent of the timekeeping gear train, explaining the separate barrel. This setup is essentially the same for almost all grande sonnerie watches, wrist or pocket.

In comparison, minute repeaters make do with a simpler mechanism since they only chime the time on demand, a function typically activated via a slide on the case. That’s because a repeater mechanism is powered by its own, small spring that is wound up by the action of pulling on the slide. The spring then discharges to run the strikework.

For comparison, a 19th century, minute repeating movement installed in a 20th century Patek Philippe wristwatch

Grande sonnerie winding

The best historical clockwatch movements often relied on the winding mechanism similar to the Philippe Dufour Grande Sonnerie, namely one with a central, fixed crown wheel and winding clicks integrated onto the barrels. They are amongst the most prominent components on grand sonnerie movement, and perhaps for that reason are usually finished to an exceptionally high level.

This mechanism is considered the most sophisticated method of winding the two barrels due to its complexity and the need to make the components by hand. Simpler, contemporaneous alternatives include the rocker system invented by Cesar Racine and most often found in Zenith grande sonnerie pocket watches (as well as the recent Bexei Vox Vinum that relies on a late-19th century ebauche).

Beyond its pleasing aesthetics, the winding mechanism in the Dufour grande sonnerie is its optimum efficiency. Unlike the rocker mechanism, the traditional grande sonnerie system has no “dead zone”, the instant when no winding occurs as the rocker switches from one barrel to another.

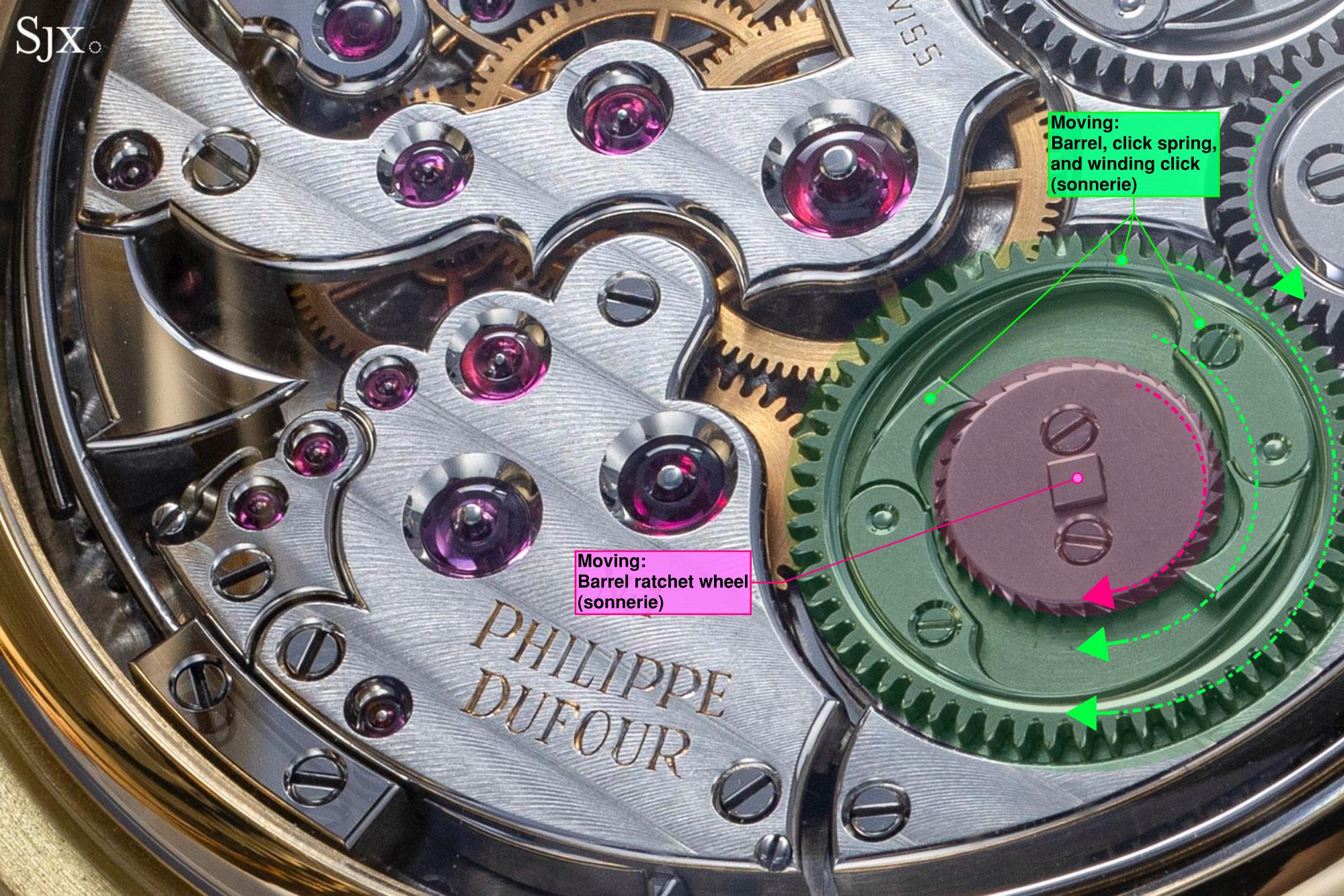

Figure 2: The key elements of the winding mechanism

The annotated photo above provides the lay of the land: the timekeeping barrel on the left (blue), and the sonnerie barrel on the right (green). On top of each barrel sits a barrel ratchet wheel, and on top of that a pair of clicks and click springs.

The clicks act as a one-way clutch that allow a barrel to be wound when the crown in turned in one direction, but slip when the crown goes in the opposite direction, and vice versa. That’s how both barrels can be wound via the crown.

The crown does that with a crown wheel that meshes with both ratchet wheels. When the crown wheel turns counterclockwise, the sonnerie barrel is wound, while the timekeeping barrel remains stationary (arrows in fig. 2 indicate the direction of rotation).

And turning the crown in the other direction sends the crown wheel moving clockwise, which winds the timekeeping barrel while leaving the sonnerie barrel stationary. This inverse motion of crown and barrels explains why the winding clicks on each barrel are installed in opposing directions relative to each other.

Figure 3: Winding the sonnerie barrel. A large gear acts as the barrel cover and on it top sits the winding click that is attached to the click spring, which in turn is screwed onto the barrel cover. Both the winding click and click spring sit within the perimeter of the barrel, as opposed to being outside would be the case in a conventional movement.

When the sonnerie barrel is being wound for instance, the beaks of both clicks push against the vertical side of wolf’s teeth on the barrel ratchet wheel. As a result, both clicks catch the barrel ratchet wheel and cause it to rotate. Since the barrel ratchet wheel holds the barrel arbor, this causes the mainspring to wind more tightly around its central axis – the barrel is thus wound up.

Figure 4: The timekeeping barrel remains stationary as the sonnerie barrel is wound

As the sonnerie barrel is being wound, the opposite is happening with the timekeeping barrel. Here, the beak of the click is dragging along the sloped sides of the wolf’s teeth on the barrel ratchet wheel. Because of the sloped teeth, the click slips past each tooth – producing the distinctive “click” – allowing the barrel ratchet wheel to remain stationary as the clicks slip over the wheel.

But that is only half the story, quite literally. Hidden under each barrel ratchet wheel is the other half of the winding mechanism.

Each barrel ratchet wheel conceals another set of clicks and click springs. These prevent the barrel ratchet wheels from turning backwards and the barrel from unwinding when the crown is released. This explains why the barrel ratchet wheels appear to sit high above the mainsprings, and partially explain the substantial height of a grande sonnerie movement.

The conventional winding mechanism of a minute repeating movement with a crown wheel (right) and barrel (left), along with a fixed winding click and click spring

Flourishes galore

Though the Grande Sonnerie’s movement is functionally similar to vintage pocket watches with the same complication, it boasts all of the decorative flourishes that mark out Mr Dufour as a master of finishing.

In fact, the Grande Sonnerie movement is almost identical to calibre found in the five Audemars Piguet pocket watches, but Mr Dufour evidently took the decoration one step further. While the movements in the Audemars Piguet watches already incorporated the sharp inward and outward angles within the bevelling that enthusiasts so like, Mr Dufour further enhanced them in his own watch.

The genteel, sometimes subtle decoration found in 19th century watches has been turbocharged in the Grande Sonnerie movement. Mr Dufour accentuated the angles and curves to create the almost exaggerated anglage that has become his trademark – and later served as inspiration for watchmakers like Rexhep Rexhepi of Akrivia. Simultaneously, he inverted the outline of adjacent components, which means a sharp outward angle on one component is mirrored by a sharp inward angle on another, enhancing the visual impact of all the sharp points.

The L-shaped train bridge, for example, is relentless in including as many corners as possible within its outline

The train bridge forms a frame for the balance and escapement

Another wonderful detail: the oversized yet elegant swan’s neck regulator index, an upgrade not found in the movements made for Audemars Piguet. And the hairspring is held in place via a traditional kidney-shaped stud piton that is finished like the rest of the movement – perfectly.

A feature common to many of Mr Dufour’s earlier work is occasionally inconsistent hand-engraving

Up close, the movement decoration is unsurprisingly superlative. It helps that a pocket watch has scale – every component is larger, resulting is higher resolution for even the tiniest of details.

The size of the barrels and winding clicks become apparent when comparing them against the bridges and going train wheels

The scale of the movement is most obvious on the height of the bridges and wheels, which allows for pronounced chamfering on all edges

The height of the bridges is also illustrated by the depth of the bowl-shaped countersinks

The perfect finishing on the outer edges of the bridges reveal the uncompromising attention to detail

The frosted bridge for the pallet lever is barely visible but perfectly executed

Impeccable finishing of three types on the barrel ratchet and clicks: frosting, circular graining, and mirror polishing

The lustre of the hammers and Cotes de Geneve

A weighty watch

The rest of the Grande Sonnerie is a typical of a high-quality pocket watch and practically identical to the Audemars Piguet watches that came before.

At 60 mm in diameter, the case is large, heavy, and imposing (but not enormous on a coach-watch scale like the recent Vacheron Constantin Vermeer). Made of yellow gold – what else would a traditional pocket watch be? – the case is simple but finely crafted, revealing a quiet, workmanlike quality.

The slide on the case band to select the strike mode of the sonnerie

Solid hinges secure the twin backs that close with a crisp snap

The maker’s hallmark, or Poinçons de Maître, on the inner back indicates the case was produced by the long defunct firm of Bernard Paratte of La Chaux-de-Fonds

The inner back is engraved with minimal text, including the all-important “No 1” that signifies this was the first example

The engraving was naturally done by hand

And on the front, the restrained, old-school aesthetic continues. The dial is glossy white fired enamel with blued spade hands. Every single detail, from the typography to the proportions, echoes 19th century watchmaking.

It is almost a shame that the intricate strikework is hidden behind the simple dial, as it is undoubtedly finished as well as the visible portion of the movement. That was no doubt the rationale behind the clear sapphire dial Mr Dufour later devised for his final pair of Grande Sonnerie wristwatches.

The sunken seconds register is a separate disc of enamel soldered to the main dial, with the border revealing the faintest trace of solder

Concluding thoughts

The Grande Sonnerie pocket watch is clearly a masterpiece, if for nothing more than the sheer number of man hours put into its completion. That 2,000 hours and Mr Dufour’s obsessive approach to decoration means that the details of the movement are magnificent to behold.

Beyond its intrinsic beauty, the Grande Sonnerie pocket watch is a landmark for being one of the earliest Swiss watches to bear the name of an independent watchmaker on its dial. Timepieces like this provided the impetus for future generations of watchmakers to strike out on their own.

Back to top.