History’s most famous reversible wristwatch would never have been invented were it not for Joseph Ford Sherer, then a lieutenant in the 44th Regiment of Sylhet Light Infantry of the East India Company’s army.

The story begins in the middle of the 19th century in Manipur, a state in east British India, where Lieutenant Sherer observes locals play a game known as sagol kangjei. Translating as “horse hockey”, the game was long played by local royalty. The game has players on horseback wielding sticks to hit a ball across a rectangular field. The Lieutenant reported his observations to his boss, Captain Robert Stewart.

The two men eventually began to play the game, which evolved into what is now known as polo. In March 1859 Sherer and Stewart established their own polo club, Silchar Kangjai Club, and four years later the earliest written rulebook for polo was. With that, the pair started a long tradition of polo-playing among British soldiers in India. And soon polo would find its way around the world with polo-playing soldiers across the Commonwealth – the first polo match was played in Europe sometime in the late 1860s.

Lieutenant Joseph Sherer, Assistant to the Superintendent of Cachar (second from left), with his bearers, Manipur, 1861. Image – National Army Museum

As the game grew in popularity, a problem arose: polo players would often damage the crystals on their wristwatches, sometimes with errant mallets. During a visit to India in 1930, César de Trey encountered polo-playing British officers who sought a robust timekeeper for use during the game. Swiss native De Trey had become prosperous as a manufacturer of dentures, though his own passion was watches, so much so that he opened a watch store in Lausanne in the 1920s.

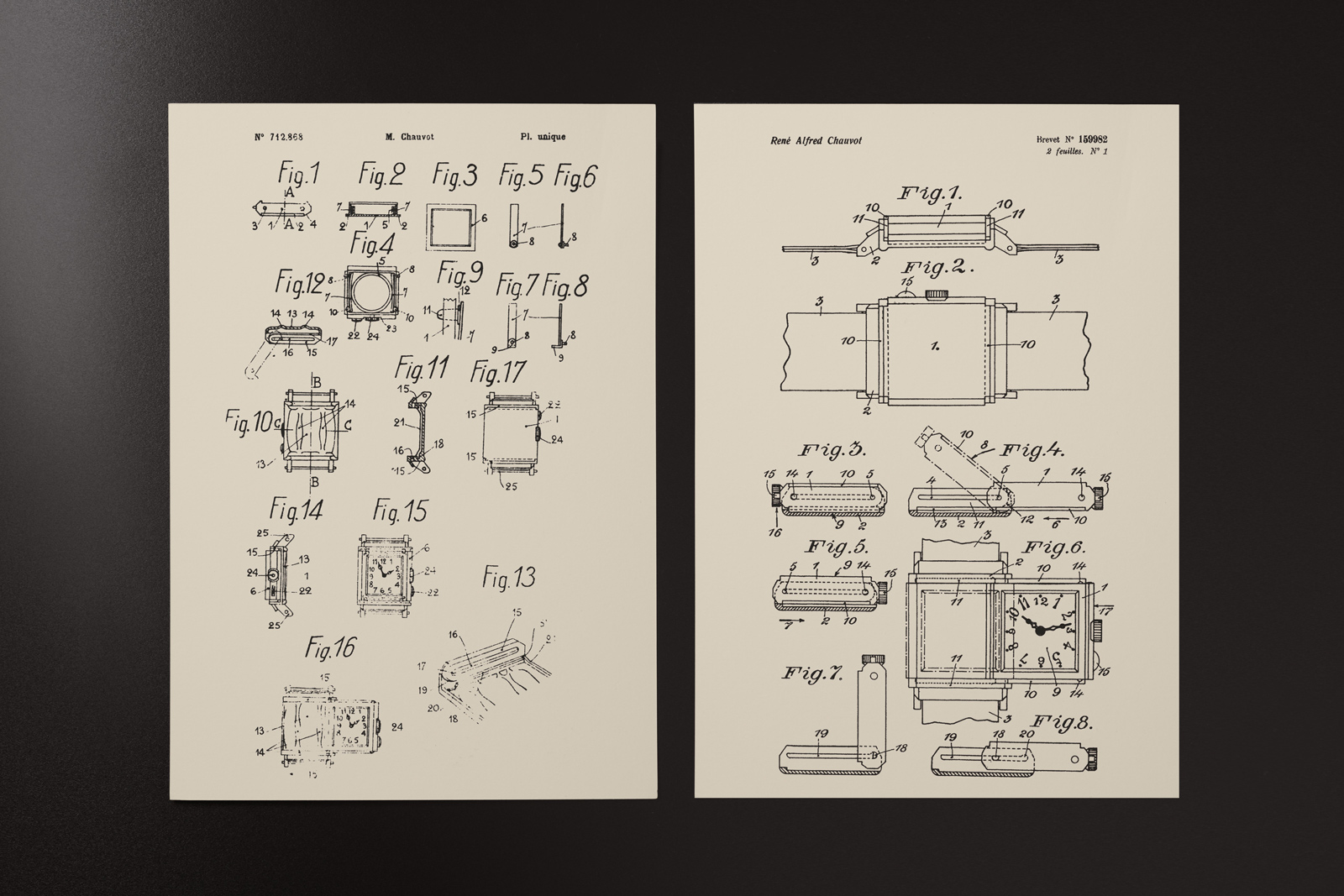

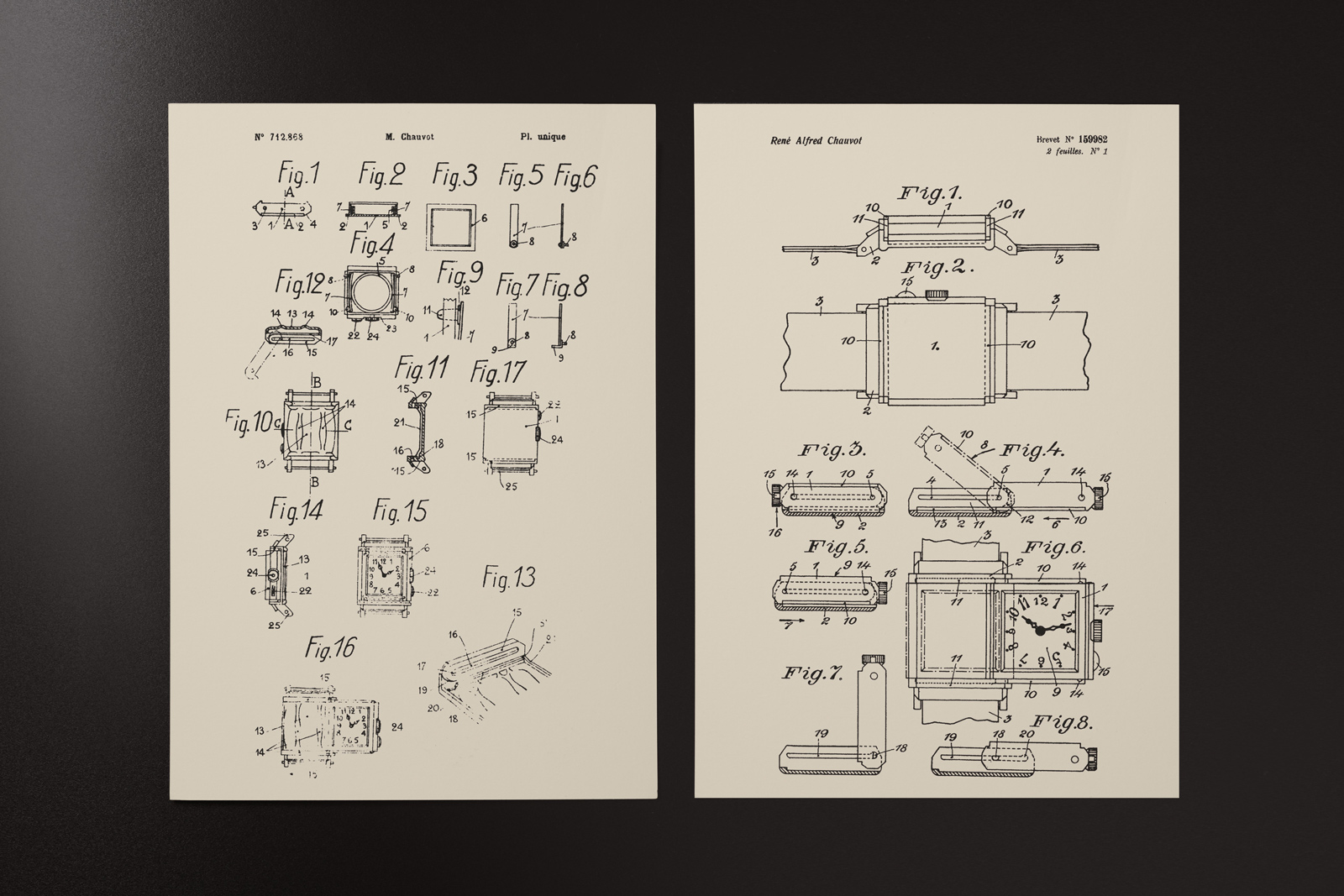

For a solution to the polo players’ problem, de Trey sought out Jacques-David LeCoultre III, the third generation of the LeCoultre family to run the eponymous watchmaker, which already had a partnership with the Parisian firm founded by Edmond Jaeger. The pair then recruited French designer Réne-Alfred Chauvot to design a watch capable of withstanding the rigours of polo.

The drawings for the patent filing. Image – JLC

That resulted in the Reverso – which is Latin for “turn back” or “turn around” – a wristwatch that had a case primarily of two parts, one of which was a swivelling capsule that could be pivoted 180 degrees on a hinge. And thanks to parallel grooves that formed a track to slide the case, as well as spring-loaded pins as a locking mechanism, the capsule could be flipped over and locked, so the watch crystal would be facing the wrist.

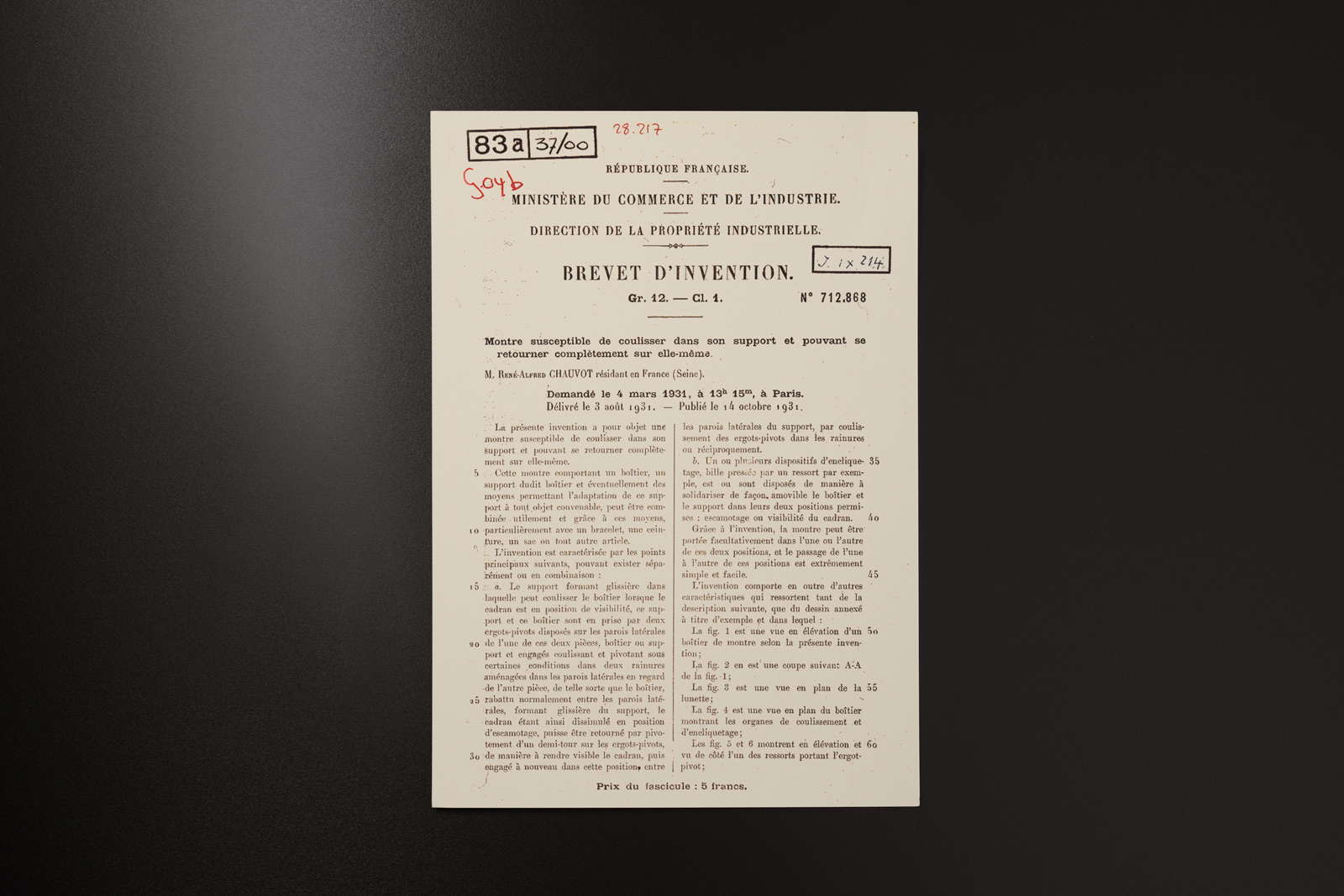

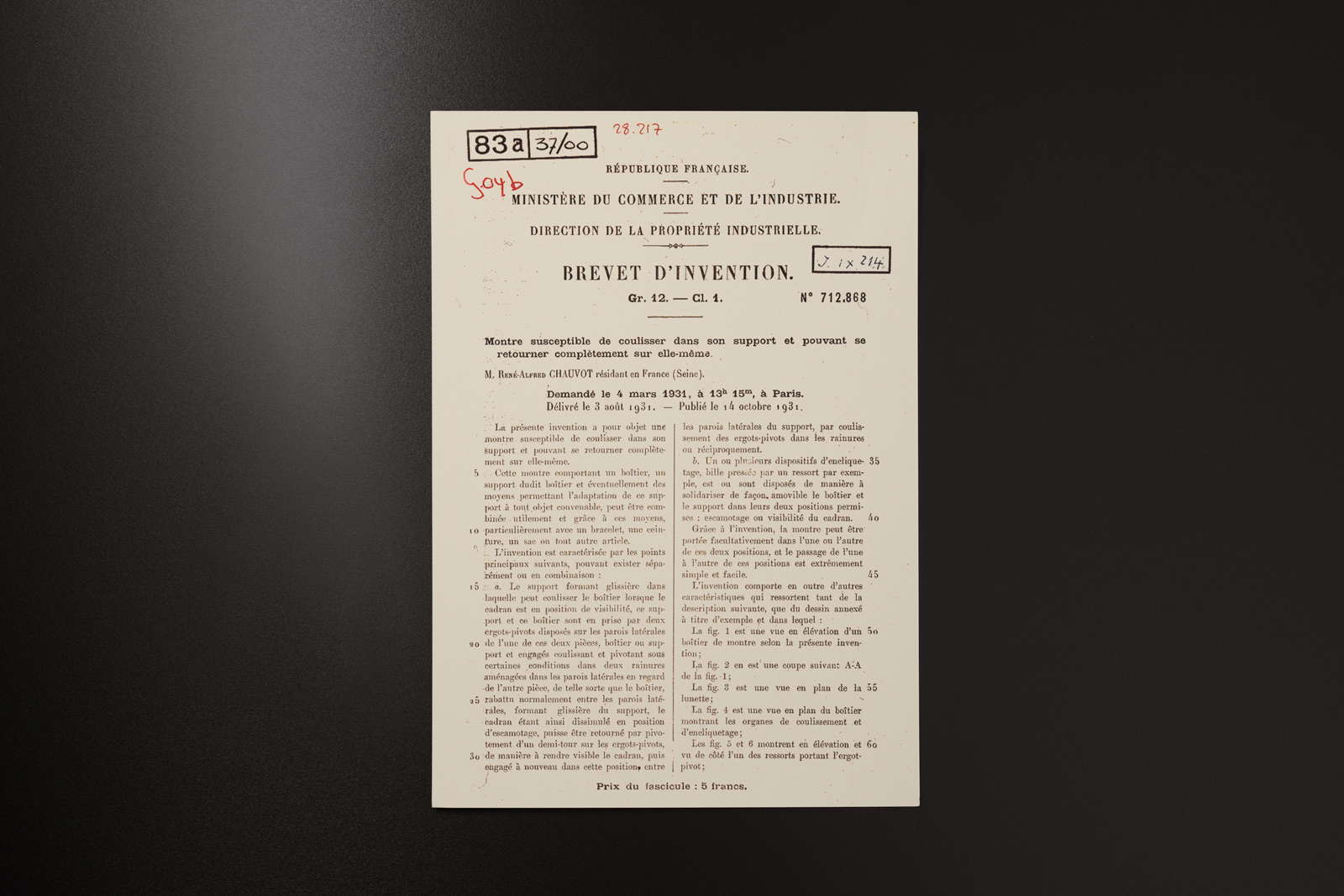

The reversible case was patented on March 4, 1931 by Chauvot. Soon after de Trey bought the patent from Chauvot and subsequently established Spécialités Horlogères S.A. in partnership with LeCoultre. The purpose of the firm was to distribute watches made by Jaeger and LeCoultre watches, including the Reverso, and it soon acquired the Reverso patent.

The original patent document. Image – JLC

Till today, Jaeger-LeCoultre (JLC) still refers to the Reverso as an invention conceived out of necessity on the polo fields: “Its dial is smoothly concealed by reversing the case, to reveal a back that fully protects the face from possible mallet strokes”.

An original Reverso from 1931. Image – JLC

But the Reverso was not the only watch invented to protect the crystal during the period, when wristwatches were in their infancy and relatively delicate. Wristwatches were delicate enough that pocket watches were considered more appropriate for arduous activities. Several inventions were devised to protect the watch crystal on the wrist, including grilles or sliding shutters, but it is the reversible case that has stood the test of time.

A 1930 “shutter” watch by Vacheron Constantin. Image – Christie’s

Consequently, LeCoultre was not the only brand exploring reversible cases in the early 1930s. At the time, Jacques-David LeCoultre was an administrator of Patek Philippe – the two companies started a commercial relationship in 1902 – which resulted in eight Reverso cases being delivered to Patek Philippe between 1931 and 1932.

These Reverso cases became the Patek Philippe ref. 106. One example is in the Patek Philippe Museum, and the last time another emerged publicly was at Christie’s in 2010, where it sold for CHF147,000. And a decade before, an exceedingly rare version in white gold with a black dial sold for more than double that at Antiquorum.

The Patek Philippe Reverso originally sold by Gübelin in 1932 that achieved CHF140,000 at Christie’s in 2010. Image – Christie’s

But the most famous reversible case aside from the Reverso comes courtesy of Cartier – though it shared the same inventor. In 1933, the Parisian jeweller debuted a watch then known as the Cabriolet, but better known today as the Tank Basculante.

Perhaps inspired by the Tank of 1917, it was equipped with a case that could flip like the Reverso, but on along the vertical axis, rather than the horizontal axis of the Reverso.

The design allowed the Cabriolet to rotate 360 degrees, as opposed to the 180 degrees of the Reverso. Like the Reverso, the Cabriolet was patented by Spécialités Horlogères S.A., the company owned by de Trey and LeCoultre that later evolved into Jaeger-LeCoultre.

A Cartier Cabriolet from 1964. Image – Christie’s

The rise…

While its origins were prosaic, the Reverso’s form was conceived according to the golden ratio, a classical standard for geometric beauty.

The length-to-width ratio of the Reverso case conforms to a ratio of approximately 1.1618. Also known as the divine proportion, that ratio can be found in the natural world and is often considered aesthetically pleasing. German astronomer and mathematician Johannes Kepler noted that “the image of man and woman stems from the divine proportion”.

Another example of a 1931 Reverso. Image – JLC

Another crucial element of the Reverso’s inimitable style is its Art Deco inspiration. The prevailing design movement of the period, Art Deco began in the 1920s and continued to dominate design in the West until the Second World War. The triple gadroons – essentially decorative fluting – on both the top and bottom edge of the swivelling case typify the clean lines of Art Deco.

While the case design and proportions have largely remained consistent throughout its history, the Reverso has been iterated into a great number of variants, right from its birth in fact. Amongst the earliest Reverso watches is a pendant watch made in 1931. Also on offer from the start were smaller Reverso watches for ladies.

A 1931 pendant Reverso. Image – JLC

A 1937 example. Image – JLC

And one from 1942 with radium numerals and hands. Image – JLC

While the very first Reverso watches flipped over to reveal a plain metal back able to resist the strike of a polo mallet, the case back almost instantly become a canvas for decoration and personalisation. Initials, monograms, and coats-of-arms are the most common motifs found on the back.

Amongst the more notable personalised Reverso watches is the 1935 example made to commemorate Amelia Earhart’s flight from Mexico City to New York in 1935, as well as General Douglas MacArthur’s own Reverso that bears his initials on the back. Both of these watches are now in the JLC museum.

The Reverso made to mark Amelia Earhart’s 1935 solo flight. Image – JLC

General MacArthur’s Reverso. Image – JLC

A 1936 Reverso with an enamel miniature painting of an Indian lady. Image – JLC

… and fall… and rise again

By the early 1950s, the Reverso has fallen out of fashion. Round watches were in vogue and evolving nature of recreational sport had transformed the notion of the sports watch. With the rising popularity of leisure diving, dive watches like the Rolex Submariner soon came to define the sports watch.

And in the late 1960s, the quartz watch came along and swept everything. Like most of its compatriots, JLC focused on the new technology, leaving behind the old ways of mechanical watchmaking – the Reverso fell prey to changing times.

One of the last first-generation Reverso watches, this one from 1952. Image – JLC

But then in 1972, the JLC distributor in Italy, Giorgio Corvo, bought the final batch of 200 Reverso cases. Corvo had JLC install mechanical movements inside and proceeded to sell every single one of them within a month, illustrating the voracious appetite for luxury watches in Italy at the time. That eye for good watchmaking has continued into the third generation with Corvo’s grandsons, Jacopo and Mattia, who now operate GMT Italia, a watch store in Milan specialised in independent watchmaking.

Inspired by Corvo’s success, JLC reintroduced the Reverso in 1975 as a quartz watch for ladies. That was followed by the short-lived Reverso II of the 1980s, which was a slightly squat-looking watch that did without the triple gadroons of the original Reverso.

While the Reverso cases historically had been made by specialist subcontractors – the Patek Philippe Reverso cases were made by Wenger for instance – JLC decided to make its own cases with the success of the resurrected Reverso.

One of its engineers, Daniel Wild, was tasked with redesigning the Reverso case to modern specifications in 1981. Four years later JLC debuted the all-new Reverso case, which was what is now known as the Reverso Classique, a mid-sized model. While the original Reverso case of 1931 was made up of just 23 parts, Wild’s creation comprised 55, making for a far sturdier and water-resistant timepiece. This revamped Reverso replaced the Reverso II and formed the genesis for the contemporary Reverso family.

A facelift

While the Reverso was endowed with a more robust case, it was repositioned as an example of mechanical excellence, rather than the sports watch it was all those decades before.

Amongst the first of the complicated Reverso watches was the Reverso 60ème, a limited edition released in 1991 for the 60th anniversary of the watch.

While seemingly simple on the front – showing just the time, date, and power reserve – the 60ème was equipped with the cal. 824 that had its bridges and base plate in solid gold, making it one of the rare few watches at the time with a solid-gold movement.

The Reverso 60ème. Image – JLC

Quite logically, the multiple faces of the Reverso became a canvas for expressing complexity. That began in 1994 when JLC released the Reverso Duoface. It was the first Reverso with two faces, each capable of showing a different time, allowing the wearer to track two time zones. The Duoface signalled the beginning of an era where complications were a key part of the Reverso collection.

The 1990s also saw the launch of several firsts for the Reverso, including the first tourbillon, first minute repeater, and first perpetual calendar, all of which were part of the “pink gold” series of limited-edition, complicated Reverso models. Naturally, all Reverso watches, regardless of complication, are powered by in-house movements developed by JLC specifically for the Reverso, making all of them form movements with a rectangular shape.

The first Reverso with a tourbillon, 1993. Image – JLC

The first Reverso with a minute repeater, 1994. Image – JLC

Two more recent Reverso watches exemplify the integration of complications into the reversible case. The first was the Reverso Gyrotourbillon 2 of 2008 that incorporated the brand’s double-axis, spherical tourbillon into a form movement. Technically and visually impressive, it was a massive watch almost 16 mm thick due to the huge calibre within.

And the other is the most complicated Reverso to date, Reverso Quadriptyque that boasts 11 complications, including a perpetual calendar and flying tourbillon, shown on four faces. Created to mark the 90th anniversary of the Reverso, the Quadriptyque features complications on four faces, being a successor of sorts to the colossal Reverso Tryptique of 2006 that featured complications on three faces.

Both the Tryptique and Quadriptyque feature a clever pusher mechanism that engages the calendar and astronomical displays contained within the lower carriage of the case once a day. This pusher advances the displays at midnight, allowing for additional displays despite the fact that the movement itself is contained with the swivelling portion of the case – a perfect example of JLC’s inventive watchmaking.

The Tryptique of 2006. Image – JLC

Reverso Quadriptyque of 2021. Image – JLC

Remembering the polo connection

JLC did not forget the sporting roots of the Reverso and unveiled the Reverso Gran’Sport in 1998. Conceived as a sports watch in the modern sense of the word, the Gran’Sport boasted 50 m of water resistance as well as the options of a rubber strap or steel bracelet.

It was characterised by a relatively thick case that was more tonneau than rectangular, and available as a time-only automatic, chronograph, or Duoface. Though the Gran’Sport remained in the catalogue for several years, it never quite took off, perhaps because it lacked the elegance of the original Reverso.

For the 75th anniversary of the Reverso in 2006, JLC replaced the Gran’Sport with another attempt at a true sports watch, though in hindsight it repeated the same mistake.

Now kitted out with an even larger case that was square, the Reverso Squadra was available with sporty complications such as the chronograph and GMT. Though it was ostensibly inspired by a rare 1930s Reverso with a similarly shaped case, the Squadra still lacked the charm of the original golden ratio design. So like its predecessor the Squadra did not catch on and was dropped after several years.

The Jaeger-LeCoultre Reverso Squadra Hometime with a dual time zone function. Image – Sotheby’s

The Reverso Tribute Duoface with a Casa Fagliano strap. Image – JLC

Despite the ironic lack of success as a sports watch, the Reverso continues to demonstrate its longevity as the signature model of JLC. It remains one of the most famous form watches in the world, equalled in stature by only a few other shaped cases, the Cartier Tank amongst them.

Ninety years after the first Reverso, the iconic reversible watch still retains its connection to polo, but in an oblique manner. When JLC introduced the Grande Reverso Ultra Thin Tribute to 1931 in 2011 for the model’s 80th anniversary, it also launched leather straps made by Casa Fagliano, an Argentinian maker of polo boots slightly older than the Reverso, having been founded in 1892.

Back to top.