Annual Swiss watch export figures recently published by trade body Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry (FH) reached an all-time high of CHF22.3 billion in 2021, with CHF 21.2 billion of that for wristwatches alone. The bumper year for Swiss watch exports – a proxy for the luxury watch industry as a whole – has just been dissected by Morgan Stanley in its yearly report on the Swiss watch industry published in in collaboration with LuxeConsult, the watch industry specialist consultancy I founded.

The key piece of good news in the report: the business has returned to pre-Covid level of sales, with Swiss watch exports up 31.2% compared to 2020, and even 2.7% higher than 2019. The bad news is that despite an increase of two million watches in the year, the volume of exports remains 4.9 million units below that of 2019.

Still wearing the crown

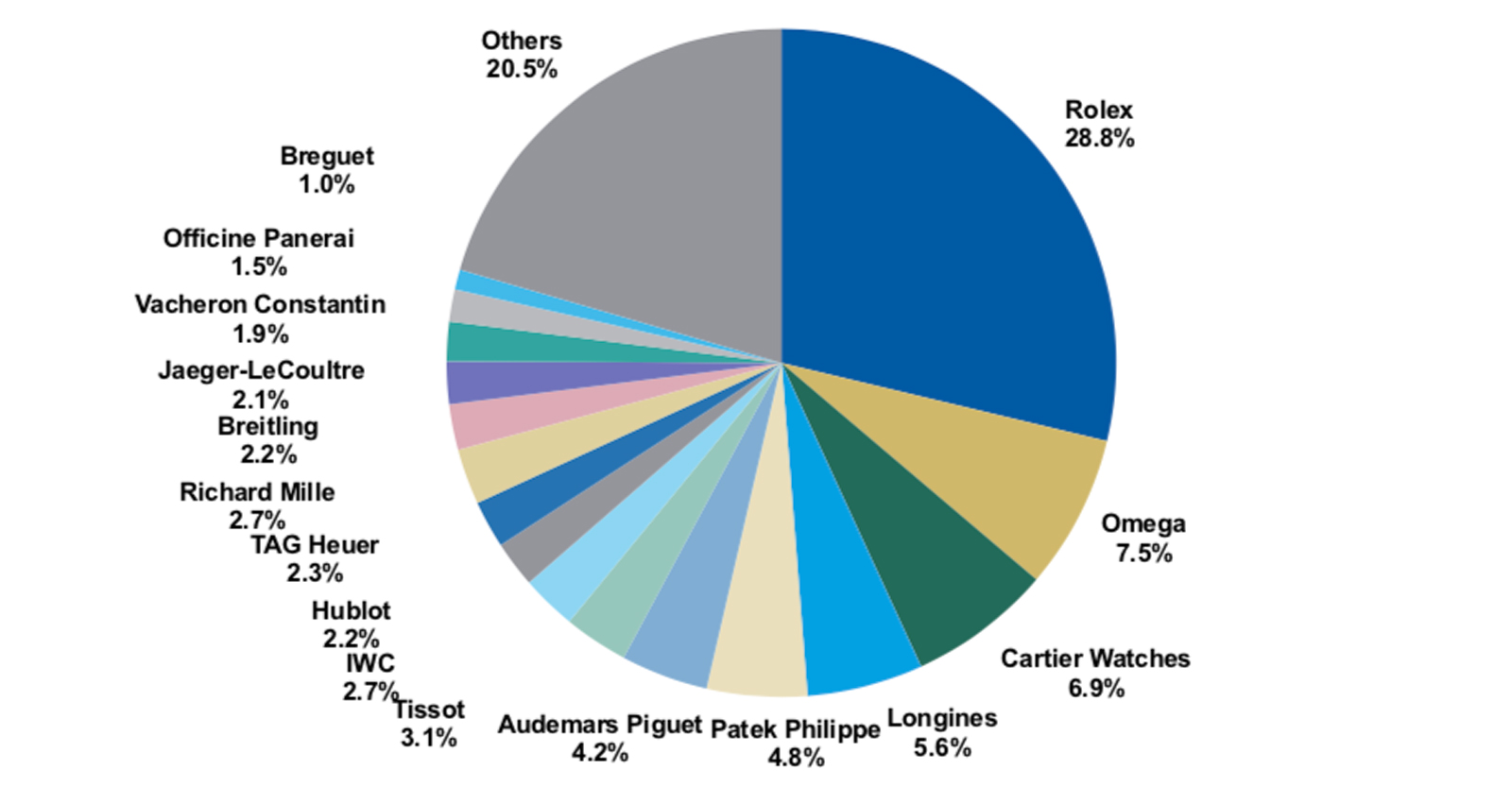

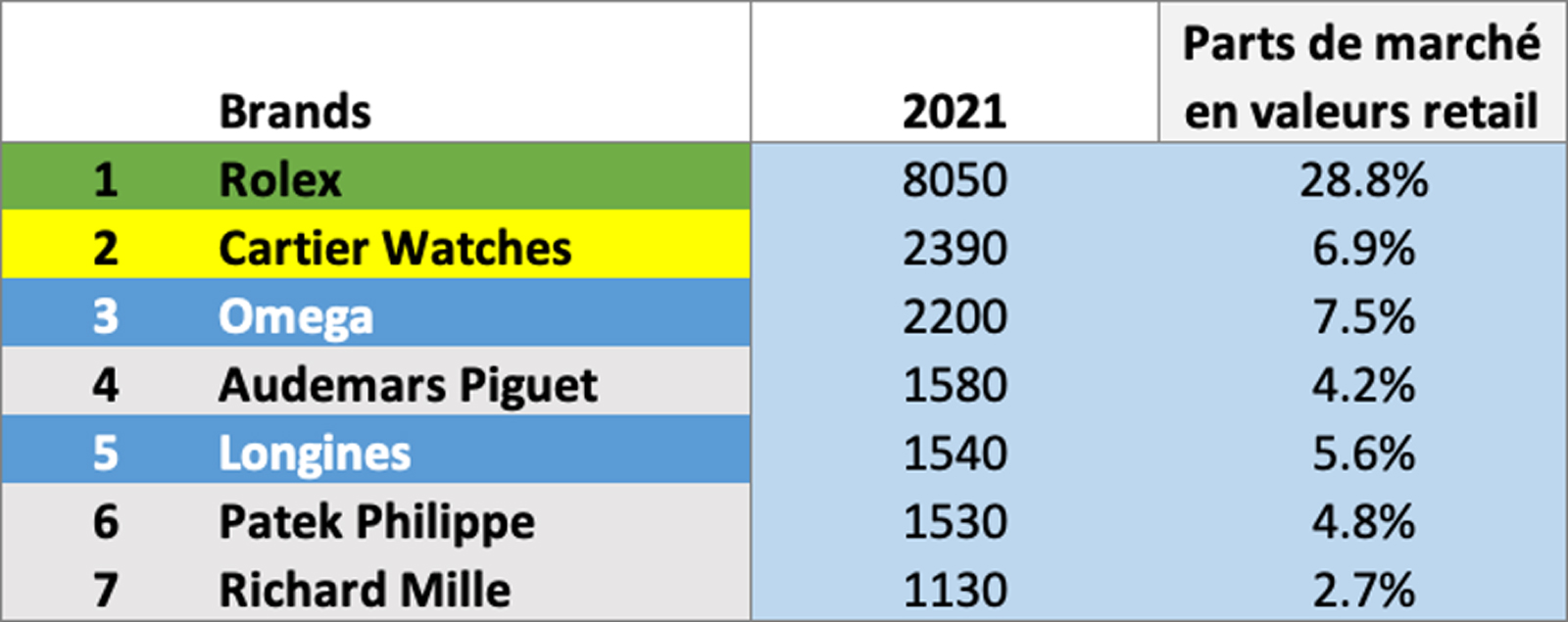

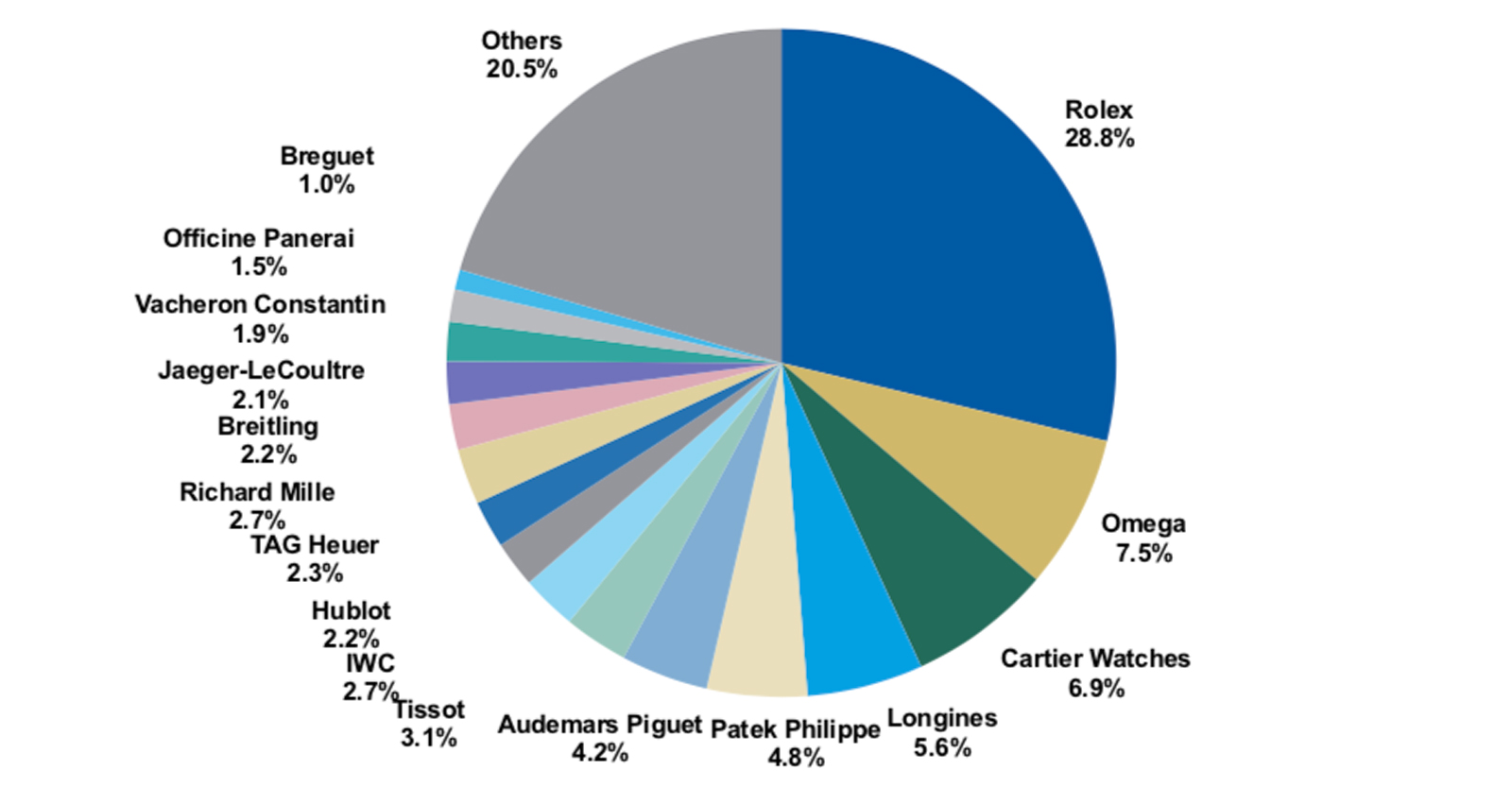

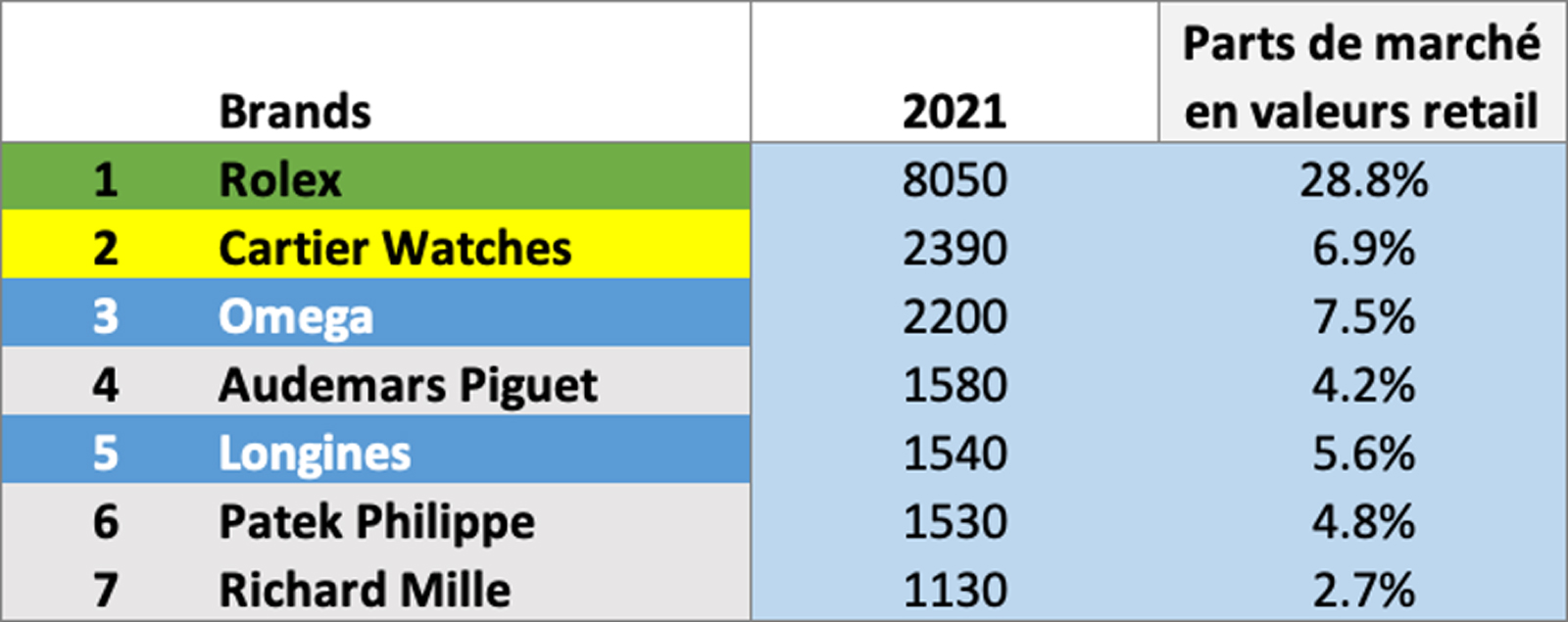

Unsurprisingly, Rolex remains the leader amongst Swiss watch brands with 29% of market share and an estimated turnover of CHF8 billion in 2021.

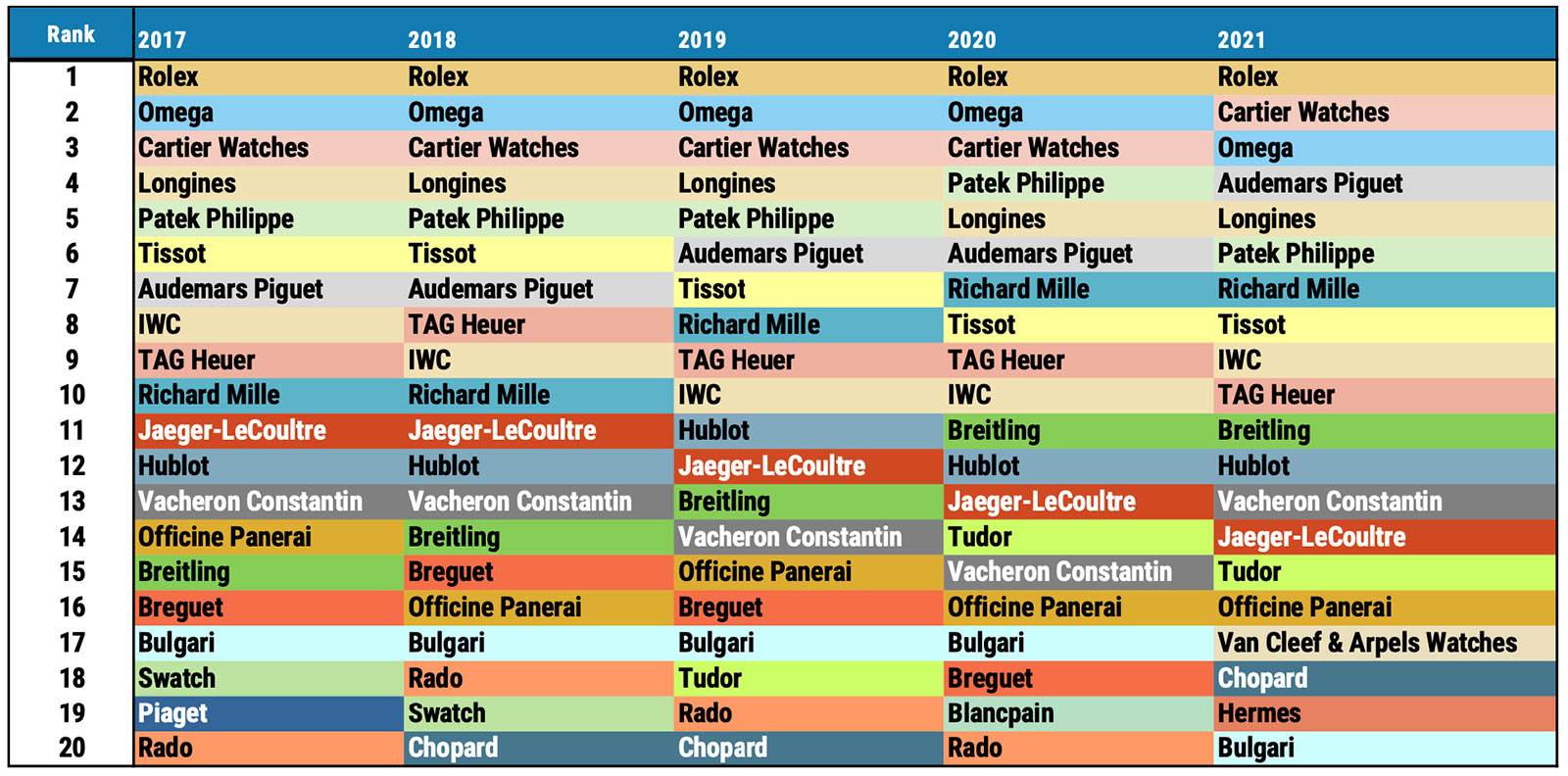

In second place is Cartier with CHF2.39 billion, which corresponds to a 40% year-on-year increase. Because of that, traditional second-place finisher Omega is now third with CHF2.2 billion in sales.

Estimated market share according to retail sales. Source: LuxeConsult, Morgan Stanley Research. © This graphic may not be reproduced without the express permission of Morgan Stanley.

The estimated sales and market share of the top seven brands. Source: LuxeConsult, Morgan Stanley Research. © This graphic may not be reproduced without the express permission of Morgan Stanley.

Rolex’s record revenue means it not only enjoyed the best year in its history, but managed to stage a remarkable comeback after an estimated 20% drop in production in 2020 due to the pandemic shutdown.

To better understand the scale of Rolex, its market share (at retail value) of 28.8% is as much as the next five brands combined.

The turnover of Rolex itself is CHF1 billion more than that of the Swatch Group, which owns 17 watch brands, including Omega and Longines. And we add Tudor into the numbers with its annual sales of CHF510 million, Rolex achieves CHF8.5 billion in revenue – 20% more than the Swatch Group.

And Rolex’s strength is almost uniform across the world. Its market share in the two of the biggest markets for Swiss watches is 40% in the United States (the world’s largest market for Swiss watches) and 35% in the United Kingdom (the fifth biggest market). No other luxury brand has such a dominant position in key national markets.

The polarisation cycle

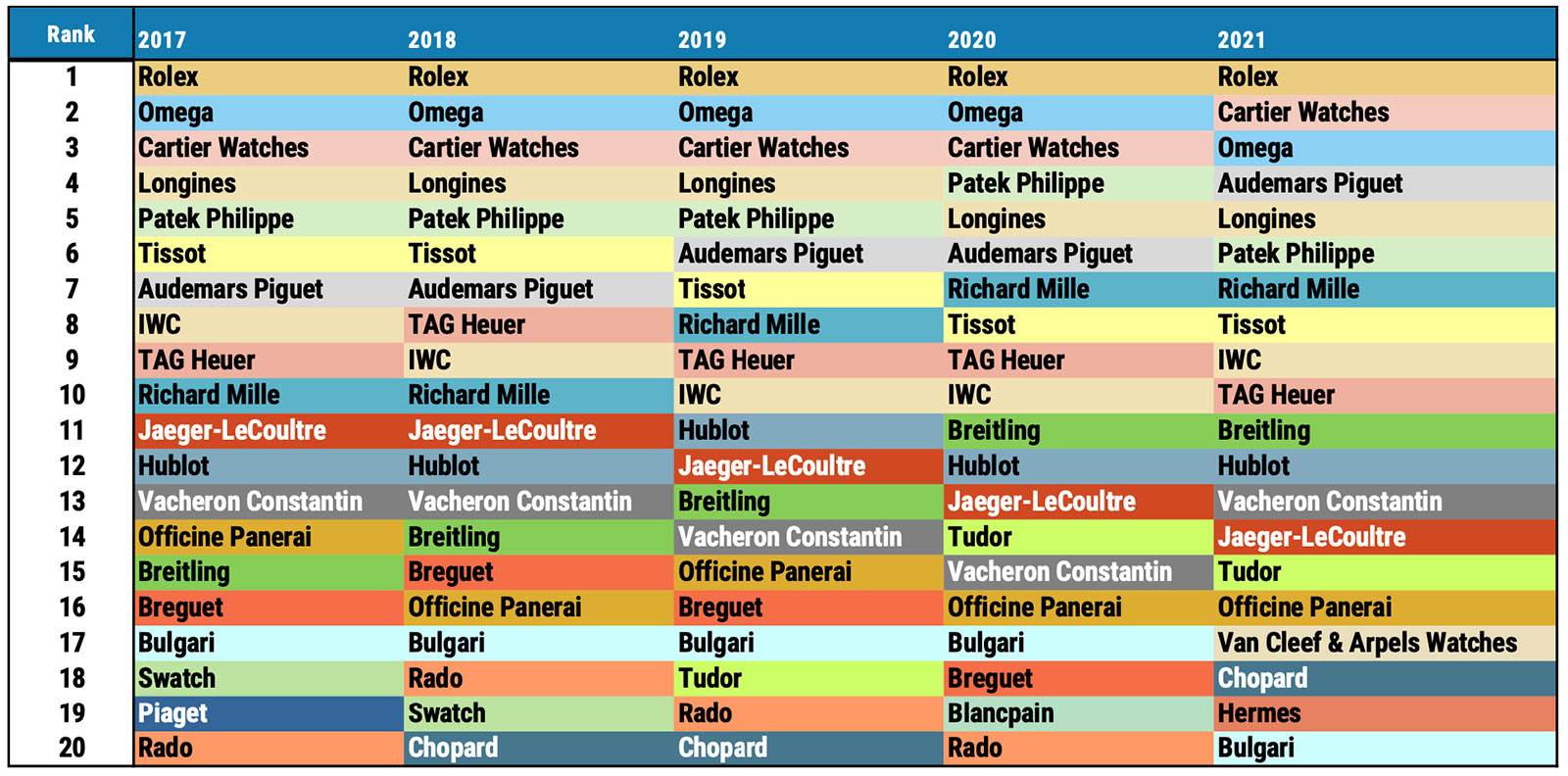

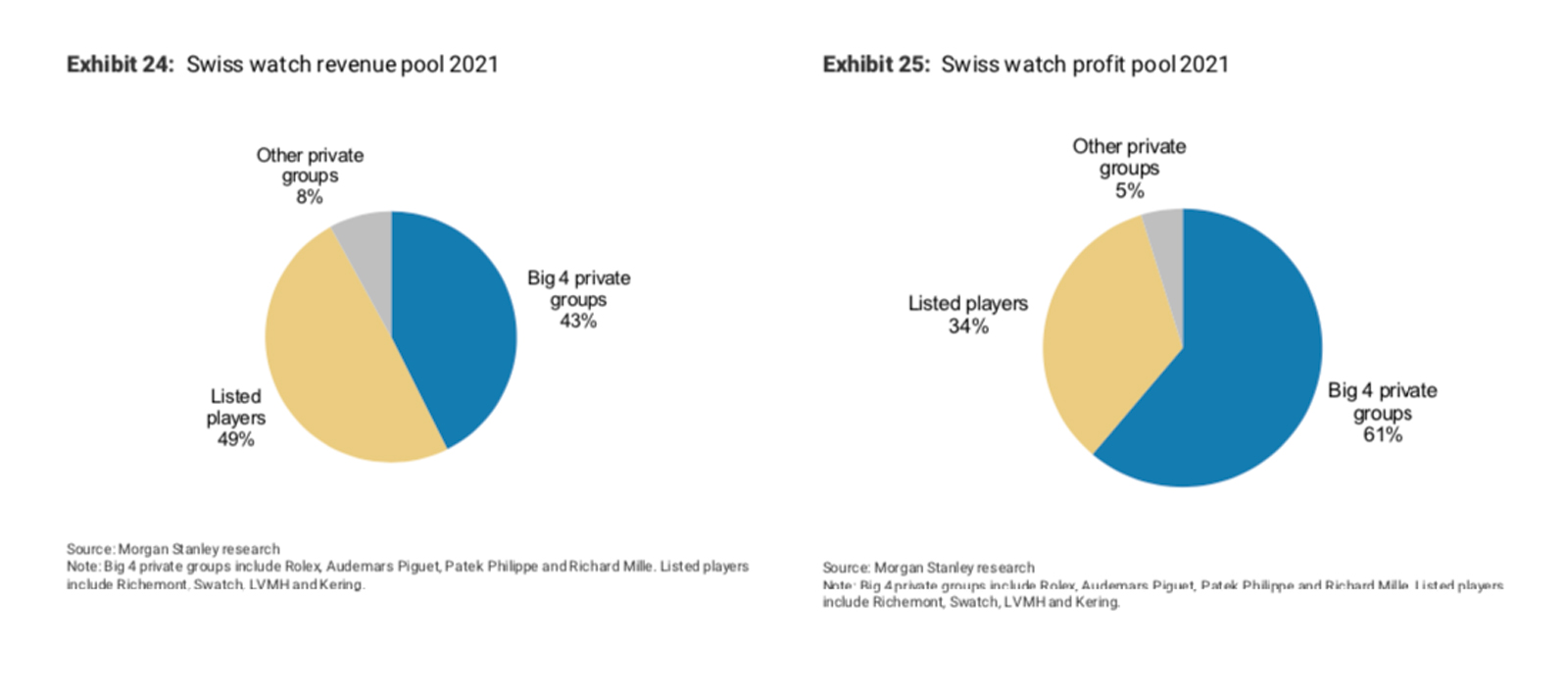

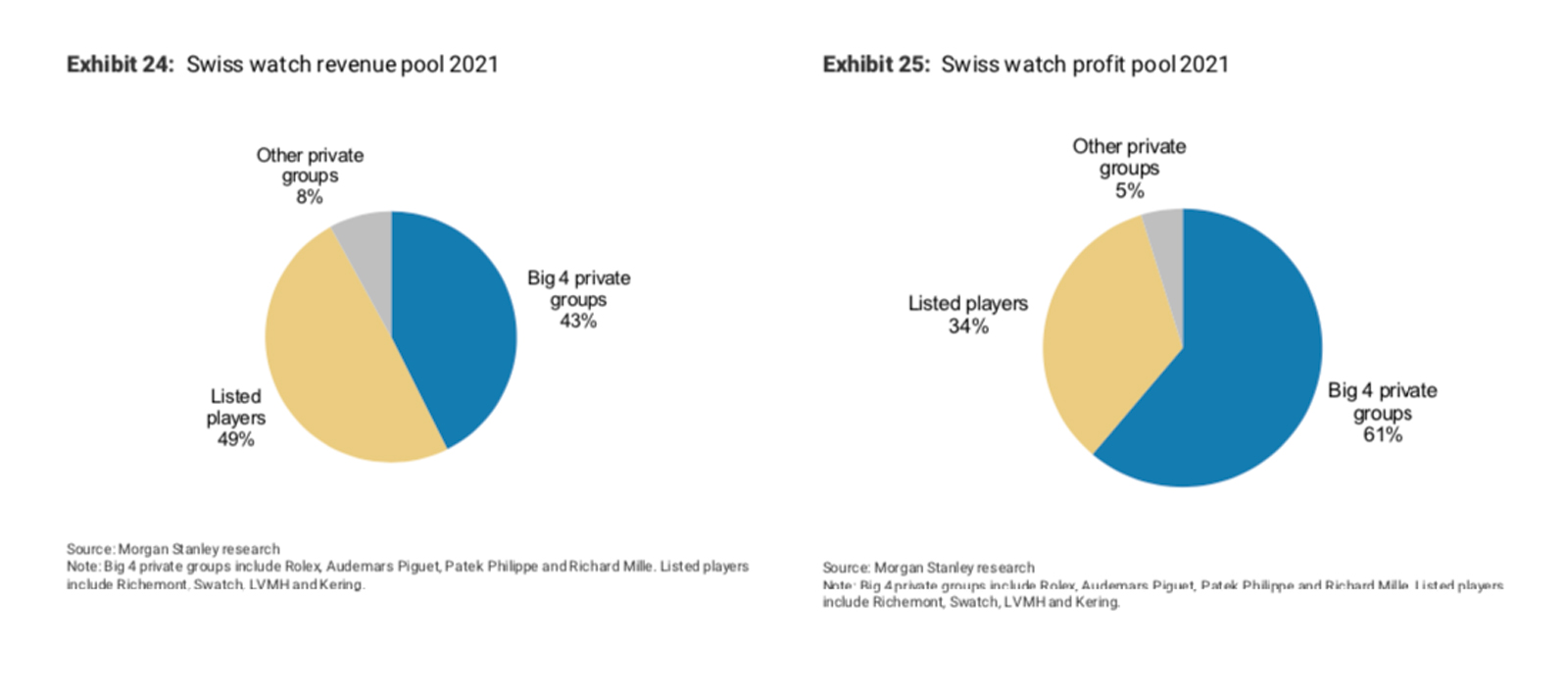

For several years now, we have been witnessing an accelerated polarisation of the watch industry, where a few brands outperform, allowing them to reinvest in product and marketing, creating a virtuous cycle that further boost sales. Such brands enjoy margins that grow more quickly than turnover. To put it simply: the more a brand sells, the more its profitability increases, which gives more means to be more visible.

This is most pronounced with the four brands that have exhibited the strongest growth for several years – Rolex, Audemars Piguet, Patek Philippe and Richard Mille. And just below sits a second group of runners-up made up of Cartier, Omega, Longines and IWC.

More broadly, the five most important brands represent more than half of the market, accounting for 53% of the industry’s revenue. Thirteen brands have 75% market share, while 25 brands have 90% of the market. The entire watch market, in contrast, is made up of some 350 brands.

The top 20 brands by sales from 2017-2021. Source: LuxeConsult, Morgan Stanley Research. © This graphic may not be reproduced without the express permission of Morgan Stanley.

“Premiumisation” strengthened in 2021 with the price segments of over CHF2,000 in export value (equivalent to a retail price of CHF4,000) showing the most growth in both volume and value. These premium price segments represents only 16% of volume, but 82% of value.

The entry level segment Swiss watchmaking is undeniably suffering from the onslaught of smartwatches – 80 million smartwatches were sold last year compared to barely 16 million Swiss watches. Compare this to 2016, the first full year of sales for the Apple Watch, which remains the leader in the segment with 50% of market share. That year, 22 million smartwatches sold were sold, while Swiss watchmaking sold 25 million watches, of which 18 million were quartz.

The big winners in 2021

Even though the year-on-year basis of comparison for 2021 is necessarily very low, we can highlight a few salient points.

One is the increased polarisation of the market, which is now led by a few brands that have outperformed for years (the 2018 Morgan Stanley report was the first to pick that up) and are also privately held, namely Rolex, Audemars Piguet, Patek Philippe and Richard Mille.

We can now add Breitling to this list (although Breitling is owned by private equity as opposed to a family), which is making remarkable progress with a 40% increase in revenue. These five brands represent almost half of the Swiss watch market with 43% of industry sales.

The distribution of margins is even more polarised than that of turnover. The top four brands account for 41% of sales, but 62% of the operating margins. Rolex, Audemars Piguet, Patek Philippe, and Richard Mille achieve returns that few luxury brands can match.

Industry revenues and profits. Source: LuxeConsult, Morgan Stanley Research. © This graphic may not be reproduced without the express permission of Morgan Stanley.

Rolex remains untouchable and has just notched up its best year since its founding in 1905. Its products have become almost impossible to find despite an increase in production to 1,050,000 watches, an all-time high. The consistency between the brand’s marketing message of technical excellence and its product offering makes it unstoppable.

And the brand has also made efforts in the only area where it needs improvement, namely its network of third-party retailers, some of which do not live up to the lofty standards of Rolex.

Another noteworthy development is Cartier dethroning Omega. The Parisian jeweller owned by Richemont now takes second place after Rolex with CHF2.39 million in watch sales, an increase of 40% over 2020. This reflects the dynamism of a brand that has been able to connect with a younger clientele in almost all markets.

Cartier’s performance is all the more remarkable for several reasons. One, its jewellery business experienced even stronger growth than its watch division, and two, Omega had a very good year with sales rising over 30% to put it in third place.

Audemars Piguet moved up two places to fourth position and achieved a record year, the best in its history. It overtakes historical competitor Patek Philippe which, despite its enormous desirability and the buzz created by the Tiffany & Co. edition of the Nautilus ref. 5711, did not experience the same virtuous cycle as Audemars Piguet.

Audemars Piguet is surfing on an unbroken wave of the success with the Royal Oak, which celebrates its 50th anniversary this year and will undoubtedly contribute to another record year. We estimate that almost 90% of its sales are generated by the Royal Oak and Royal Oak Offshore, but the Code 11:59 collection launched in January 2019 is starting to make its mark and accounts for 5% of sales.

At the same time, Audemars Piguet’s turnover is generated by a growing number of boutiques – now making up 75% of its revenue – which allow the brand to retain the retailer’s margin for itself, while building direct relationships with its clients. And they also help the brand better manage inventory and avoid losing sales given that its products are perennially out of stock.

The club of billion-franc brands once again has seven members with the arrival of Richard Mille in seventh position with sales of CHF1.1 billion.

The luxury groups

The winners of the recovery in 2021 also include several from Richemont, in particular Cartier, which saw its watch division revenue rise 40%, and Vacheron Constantin, which enjoyed 53% increase in sales.

Swatch Group had a very good year with a 30.7% rise in revenue, but this figure is slightly lower than the 31.4% increase enjoyed by the industry as a whole. Logically that meant Swatch Group lost market share – now down to 22% – and sits behind Rolex, which has a 30.5% share including the sales of its sister brand Tudor.

What is especially worrying for Swatch is the acceleration of Rolex compared to its historical rival Omega, which has a market share of 7.5%, equivalent to a quarter of Rolex.

Furthermore, Swatch Group is increasingly dependent on its three top brands out of its stable of 17 brands, for both revenue and profit: two-thirds of turnover is generated by Omega, Longines and Tissot, which also generate almost all of the group’s EBITDA. Omega alone is estimated to generate more than half of the group’s operating profit.

The big French groups are not celebrating because LVMH is losing market share, despite a strong performance from Hublot, which saw sales rise 45%. Zenith has almost doubled its sales, but it barely breaks even and its small size means it is relatively marginal in the group’s accounts.

And Kering, the world’s second-largest luxury group and owner of Gucci, threw in the towel at the start of 2022 and sold both of its watch brands, Ulysse Nardin and Girard Perregaux. Both have only seen sales plummet since they were taken over by the French group. Their turnover has become negligible relative to the group and both one lose money on an operating basis. With their disposal, Kering’s sole watchmaking division is at Gucci, a brand where it has enjoyed considerable luck and success.

We should also mention the watch division at Hermès, which achieved a stellar performance of a 73% increase in revenue, even if its turnover of CHF364 million places it in 19th position. Its phenomenal progress is the culmination of several years of investment and development to reposition the brand upwards and decouple it from the desirability of the brand’s leather goods.

The indies

Independent niche brands, such as F.P. Journe, Greubel Forsey, Voutilainen, MB&F, and Laurent Ferrier, are experiencing phenomenal demand both on the primary market for new watches and secondary market for pre-owned watches and “grey market”.

Some of them have have wait lists approaching several years and consequently decided to close the list altogether and no longer accept orders. Despite their outsize prominence, these brands have a marginal impact on industry value – they account for about 1% of Swiss watch exports by value – and even less in terms of volumes at about 0.05%.

Used, grey, and in-between

And finally, the secondary market. Estimated to be approximately half the size of the market for new watches, or about CHF20 billion, the secondary market is perhaps the most revealing in terms of brand desirability.

Resale prices give you a good idea of the scarcity of supply on the primary market, with some watches enjoying premiums to retail prices that can reach 50-150%. This is happening beyond iconic products such as the Rolex Daytona, Patek Philippe Nautilus or Audemars Piguet Royal Oak, with prices overall at a historical high, raising fears of a speculative bubble that might burst. The sale of a Patek Philippe Nautilus “Tiffany” for USD6.2 million gained headlines around the world, but also generated a speculative fever fuelled in part by newly wealthy cryptocurrency investors.

Addendum: methodology

Unlike other industries like fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG), the watch industry is a “black box”. Very few industry figures are published, except for exports that are recorded by Swiss customs and disseminated by FH.

The FH figures certainly have a disadvantage of indicating “sell-in” (watch brand sales to distributors or retailers) and not “sell-out” (sales to end consumers), but they reflect trends. Admittedly, there is a lag – which is more or less significant depending on the brand – between the moment the watch is delivered to a national market and the moment it lands on a customer’s wrist, but this is not as important as some commentators claim.

The method adopted by Morgan Stanley and LuxeConsult to convert this export data into retail market share for the 65 biggest Swiss-made brands include several steps. We cross-reference publicly available information with interviews with industry players. We also estimate the degree of vertical integration of the distribution for each brand, while also considering the margins given to distributors or retailers, which finally allows us to obtain an average public price and market shares.

Back to top.