In Depth: Louis Vuitton Tambour Spin Time Air

Inventive and original.

Since it acquired Geneva complications specialist La Fabrique du Temps in 2012 Louis Vuitton has been steadily growing and refining its complicated watch offering. Last year it debuted the Carpe Diem minute repeater with automaton, the most complex watch LDFT has developed to date.

But the signature completion of Louis Vuitton (LV) is still the patented three-dimensional jumping hours known as Spin Time. The complication relies on 12 cubes to indicate the hours, rotating one by one every hour.

Since its introduction in 2009, the Spin Time has been iterated into a variety of formats, including a GMT, regatta countdown chronograph, and most recently a glow-in-the-dark extravaganza. But its most refined form is arguably the Spin Time Air launched in 2019 that has a dozen “floating” cubes arrayed around a movement suspended between the front and back crystals.

Initial thoughts

The Spin Time Air has all the elements of an interesting watch. Both transparent and striking, the “floating” display brings to mind historical mystery timepieces, with the tall Tambour case serving as the perfect frame for the suspended display.

But it is the cubic hour display sets it apart. The hour display is truly unique, even when compared against the most exotic in independent watchmaking. It brings to mind Urwerk’s cubic display found in the UR-210, but that’s a three-dimensional reinterpretation of the wandering hours, whereas the Spin Time is actually an innovative take on the jumping hours.

Not only visually interesting, the Spin Time also functions in a tangible manner. In a quiet room the crisp click as the hour cube rotates is easily audible. It is a pleasant and reassuring reminder that the mechanics are running.

Legibility of the Spin Time display is excellent, except in the seconds just before and just after the top of the hour. In that brief period it can sometimes be difficult to figure out if the cube is showing the current hour or the one that just passed. Such minor inconveniences are integral to most unorthodox time displays, so that isn’t so much a criticism as a fact.

But the plain base movement that underpins the LV 88 is a fact. It’s likely an ETA automatic, a movement that is mechanically sound and definitely problem-free, but one that isn’t fancy or elaborate enough for a watch like this.

That said, LV is still in the stages of honing its complications so it’s forgivable at least for now. Urwerk, for instance, used the ETA Peseux 7001 for most of its early offerings. I expect the Spin Time display will one day be paired with an in-house calibre, or at least a fancier base, which would complete the package.

Starting at €60,000 in its most basic variation with a gold case, the Spin Time Air might seem like an expensive proposition, but it is actually priced well when compared to similar watches. The most obvious comparison is Urwerk, which offers the slightly simpler, wandering-hours UR-110 for about the same. And the Urwerk UR-210 and UR-220 are more complicated (and also rely on cube displays), but cost twice as much. While it’s difficult to see the Spin Time Air as a value buy (or anything made by LV for that matter), it is certainly fairly priced.

Making the jump

Powered by the LV 88 movement, the Spin Time Air gets its name from the suspended cubes that indicate the hours and are essentially a three-dimensional jump hour mechanism.

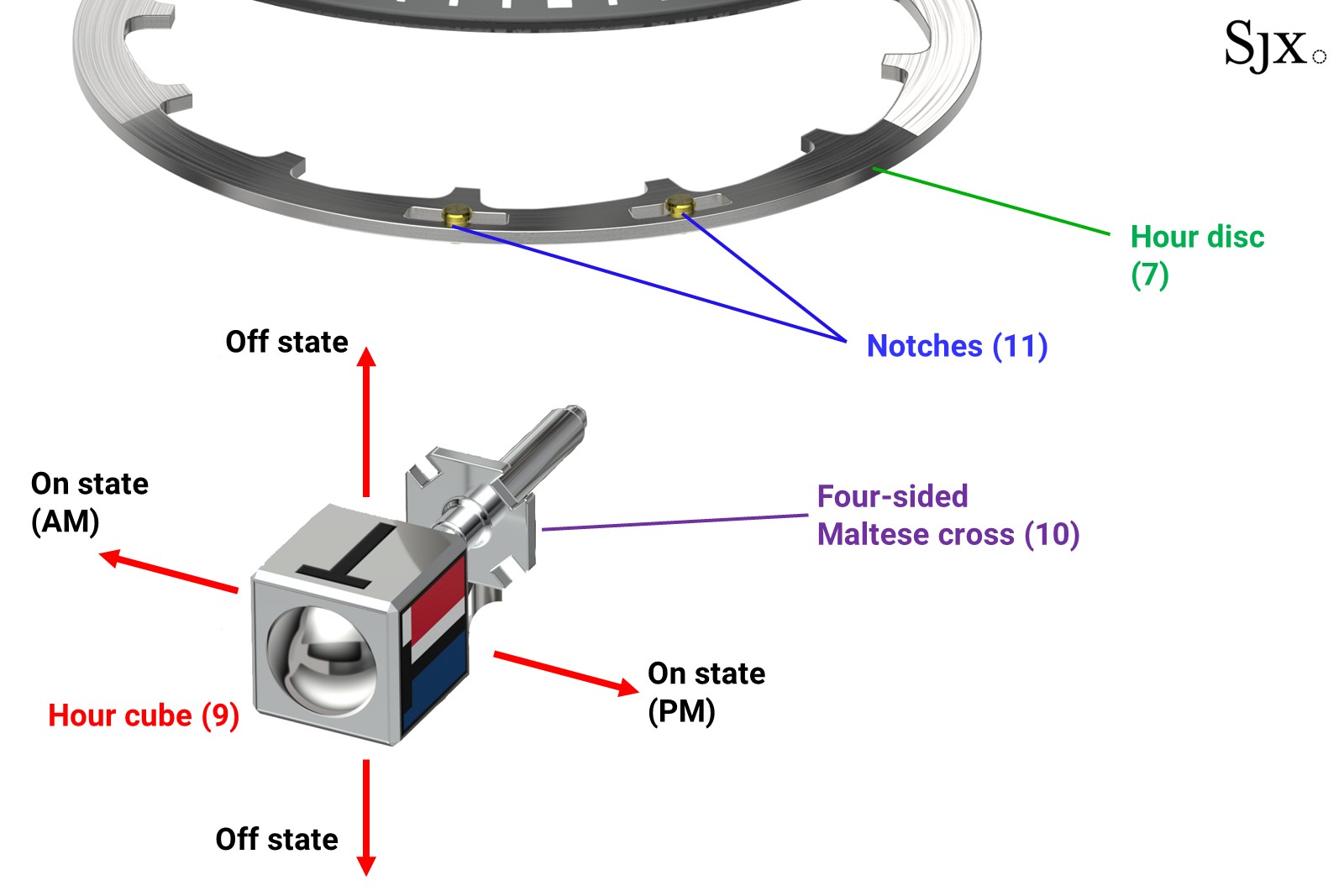

At the top of every hour, the respective cube makes a 90° jump to indicate the current hour. Because each cube has four faces, they also function as a day and night display: the black face indicates nighttime, while the yellow face means day. Other versions of the Spin Time use a variety of colours or gemstones to differentiate between day and night.

A yellow-on-black “V” indicates 3 pm

While the inverse indicate 3 am

Mechanically, the hour display mechanism is executed in as straightforward a manner possible. But this doesn’t mean it is simple, rather it has been cleverly engineered to be robust, easily to operate as well as foolproof. The mechanism, for instance, incorporates a safety feature that prevents damage to the jump hour mechanism if the crown is turned backwards.

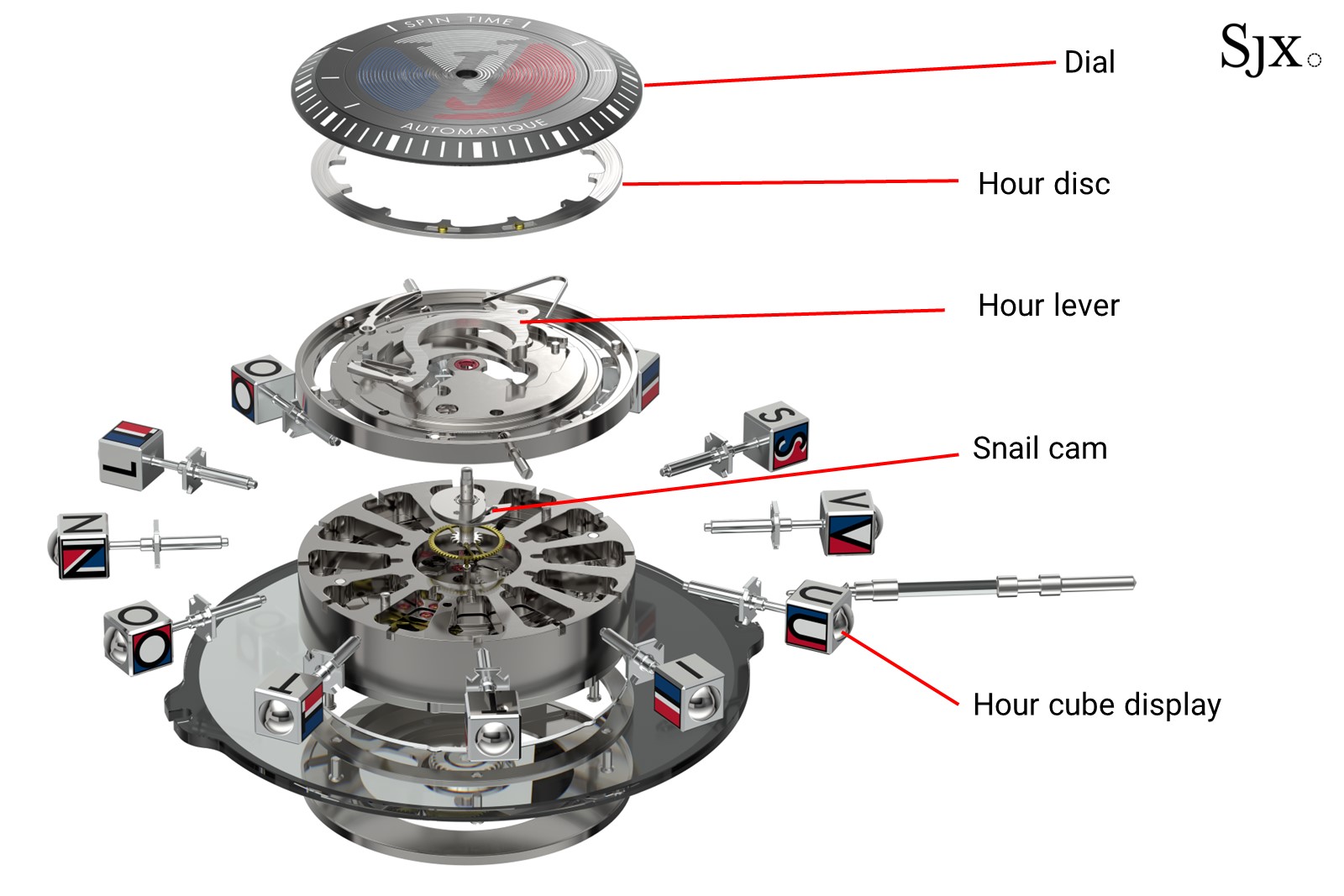

Overview of the Spin Time hour display mechanism

The base movement inside is basically an ETA automatic without an hour hand. Instead, the cannon pinion that drives the minute hand also powers the hour display mechanism.

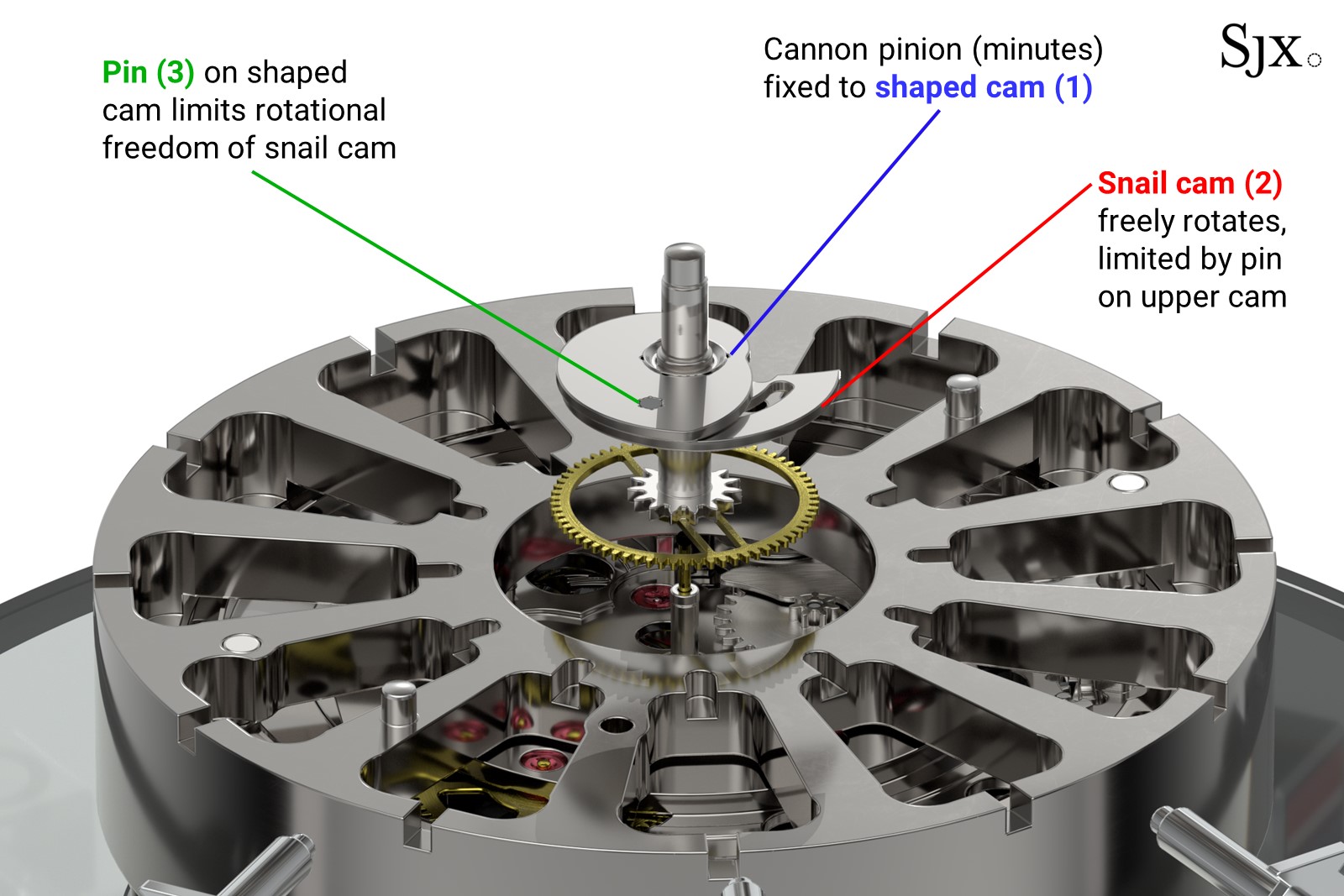

The cannon pinion has a shaped cam (1) fixed to its axis, along with a free-spinning snail cam (2) directly underneath the fixed cam. The snail cam rotates on the cannon pinion, but is dragged along by the shaped cam via a pin (3) that extends from the underside of the shaped cam and hooks into a slot within the snail cam. As a result, the pin travels along the slot before it catches and rotates the snail cam.

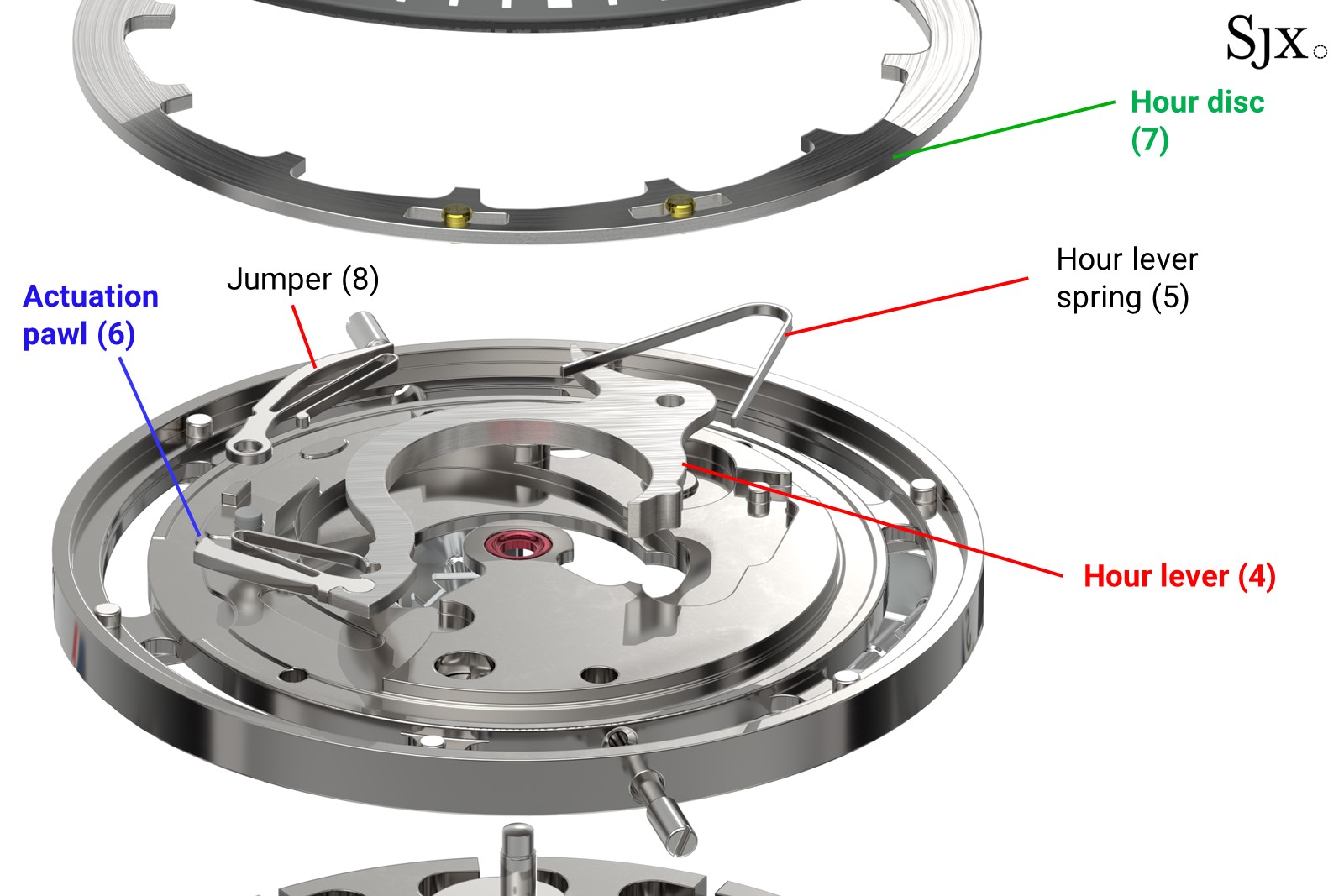

This entire assembly completes one rotation every 60 minutes. At the end of 60 minutes, it drives the hour jump mechanism starting with the snail cam pushing the hour lever (4), then storing energy in a V-shaped spring (5). The hour lever is subsequently released by the tip of the snail cam and propelled by the spring. This instantaneously causes the actuation pawl (6) on the opposite end of the hour lever to impulse the hour disc (7).

The hour disc is a ring with 12 teeth on its inner edge, along with two adjacent notches (11) on side edge of its rim. And each hour cube (9) is fixed to a Maltese cross gear on its innermost face (10). Maltese cross gears are typically used to create periodic motion, which is in case is once every 60 minutes.

The twin notches are responsible for driving the hour cubes, by rotating the respective Maltese cross by 90°. The twin adjacent notches are needed to simultaneously rotate the current hour cube to the “off” position while rotating the next hour cube to the time-telling face.

The safety mechanism of the hour display lies in the separate cams – one shaped and the other snail – on the canon piñon. They allow the minutes to be set backwards without jamming the hour mechanism.

When the crown is turned backwards (anti-clockwise in other words), the minute hand travels in reverse while the cubes remain stationary. This is because the shaped cam lifts the hour lever out of the way of the snail cam’s vertical face, disengaging the jumping mechanism and preventing damage to the components.

While the clever and complex cubic jump hour mechanism is a module made by La Fabrique du Temps (LFDT), the base movement is a compact automatic calibre that’s probably an ETA 2671 (or its clone, the Sellita SW100). Because the cubes “float” on the periphery of the dial, the movement is confined to the narrow innermost diameter of the case. Originally developed for ladies’ watches, the ETA 2671 is a perfect fit for the tiny space available.

The LV logo on the back conceals the movement

While the base movement is unquestionably robust – and importantly delivers enough torque through the gear train to reliably drive the hour display mechanism – it is still an ETA.

Accomplished independent watchmakers with similar unconventional displays, namely Urwerk and Ludovic Ballouard, do (or did in Urwerk’s case) turn to ETA for base movements, but an in-house calibre would certainly elevate the Spin Time Air to the highest level of complications. And if for nothing else, a new calibre would have a longer power reserve than the short 35 hours of the LV 88.

The drum

Introduced in 2002 with the first high-end Louis Vuitton wristwatch, the Tambour is now the brand’s signature watch case. Tambour translates as “drum”, which can also be discerned from the tall, sloping sides of the case.

With its tall sides, absence of a bezel, and oddly narrow lugs, the proportions of the Tambour case are peculiar but somehow they work. The design is distinctive without being over the top, while also being surprisingly wearable despite the large diameter.

Standing over 12 mm high, the case is thick, but that allows it to accommodate inventive complications like the Spin Time, which require space to realise. At the same time, a thin Tambour case just wouldn’t have the same visual impact.

While I appreciate the look and feel of the Tambour case, the lugs can only take straps with a specially-shaped end, which limits strap options to those supplied by LV. That is a downside as I prefer the variety possible with custom-made straps.

Liberally monogrammed

If there’s one criticism to be made of the case and dial, it is the excessive branding. The brand name or emblem can be found on the case flanks, crown, and back, and twice more on the dial. Granted the branding on the case is not especially obvious, but the oversized “LV” on the dial is hard to miss, even if it’s fairly subtle in a different shade of grey.

That said, LV is a brand that generally celebrates flamboyance, so the aesthetic of the watch is certainly in keeping with the house style.

Branding aside, the dial is attractively executed. Like the dials of LV’s other high horology watches, this dial is made in-house at LFDT in a dial workshop that even produces semi-precious stone and mother-of-pearl dials. While dial maker might seem like a secondary activity, it is a crucial skill that few brands have managed to vertically integrate. Because LV fabricates all of its own dials, it offers practically unlimited dial personalisation options, ranging from materials to colours to printing.

Varied surface finishing is employed to create different yet complementary textures. The cubes, for instance, are linearly brushed in a radial manner, while the chapter ring and flange are both concentrically brushed. That pattern is echoed by the central portion of the dial, which is stamped with a concentric guilloche.

Although simple in appearance, the cubes are impressive up close. All four faces are linearly brushed, while the edges are chamfered (via milling in a CNC machine). They are also challenging to print because each cube has to be consistent with the others, namely the letter has to be centred and printed with identical thickness. This can only be achieved by printing all 12 cubes of one dial simultaneously.

According to the manager of the dial-making workshop, trial and error with a variety of printing techniques led to inconsistent results in the early batches of cubes. Consequently, he developed a custom tool that holds all 12 cubes at once, enabling them to be printed simultaneously with the same pad. Each cube is then rotated by hand within the tool before the next face is printed.

Concluding thoughts

Because LV is a primarily fashion and leather goods brand, its complicated watches are often disdained by watch enthusiasts who fancy themselves to be sophisticated – and same applies to watches from Chanel.

The Spin Time Air is a genuinely novel complication that is clever and functional, tangible proof that a fashion house can excel in serious watchmaking. Granted the ETA base should be replaced with something more refined, but I am sure that will happen in time.

Key Facts and Price

Louis Vuitton Tambour Spin Time Air

Ref. Q1EG5

Diameter: 42.5 mm

Height: 12.3 mm

Material: 18k white gold

Crystal: Sapphire

Water-resistance: 50 m

Movement: LV 88

Functions: Hours on jumping cubes, minute hand

Frequency: 28,800 beats per hour (4 Hz)

Winding: Automatic

Power reserve: 35 hours

Strap: Alligator inlay with pin buckle

Limited edition: No

Availability: At Louis Vuitton boutiques

Price: €60,000 including VAT

For more, visit louisvuitton.com

Back to top.