I recently had a wide-ranging conversation with a fellow collector during which the following question was raised: is it possible for one watch to be objectively better than another? While pondering this question, I was reminded of Euthyphro, a Socratic dialogue written by Plato.

The “TL;DR” version is this: Plato asks Euthyphro if he can provide a definition of piety. Euthyphro responds with a clear-cut example of piety, but Plato is unsatisfied. He responds that an example is not enough; he wants the underlying rules that define piety, those by which Euthyphro chose his example.

So it is with watches. We can all point to examples of great watches, and to some extent we can defend these examples with some kind of justification. But it’s very difficult, if not impossible, to articulate a set of criteria that can be applied universally – a necessary precondition of truly objective comparison.

But as an exercise, I think it’s worth exploring in what ways, specifically, watch collecting defies objective analysis so that we can understand the limitations of this way of thinking.

Defining objectivity

Objectivity is, according to the Cambridge Dictionary, “the quality of being able to make a decision or judgment in a fair way that is not influenced by personal feelings or beliefs”.

Objectively, there’s not much more to a watch than its size, shape, colour, materials, and functions. A lot of the criteria collectors use to make value judgements about watches – such as brand prestige, rarity, provenance, beauty, and originality – are subjective or extrinsic. These characteristics are hard to judge objectively because they exist only as concepts in our minds, and differ based on individual perceptions and experiences.

The prestige of a brand, for example, is nothing more than a set of beliefs held by an individual or group. These beliefs, and thus the prestige of the brand, will vary depending on one’s own memories and experiences with the brand. Furthermore, a brand’s prestige often ebbs and flows over time in the individual and collective consciousness (anyone remember Ebel?). Accordingly, the very nature of prestige and many other extrinsic characteristics defy objective comparison.

For similar reasons, we don’t have an objective definition for what constitutes an “in-house movement” even after years of collector debate. On its face, it seems like the kind of thing that would be easy to define. But when you really start digging into it, you have to start making subjective judgements about where to draw the line.

The sieve of Eratosthenes

I approached the question of whether an objective standard for beauty might exist by thinking about prime numbers. Prime numbers exist, sprinkled among composite numbers, and their properties can be 1) derived through observation, and 2) put into algorithms like the sieve of Eratosthenes to find all other prime numbers.

I bring this up because if an objective standard of beauty were to exist, I believe we would be able to 1) derive its properties by studying beautiful watches (if we’ve made any), and 2) use these properties to identify and design other objectively beautiful watches.

The Urwerk UR-111C – objectively beautiful?

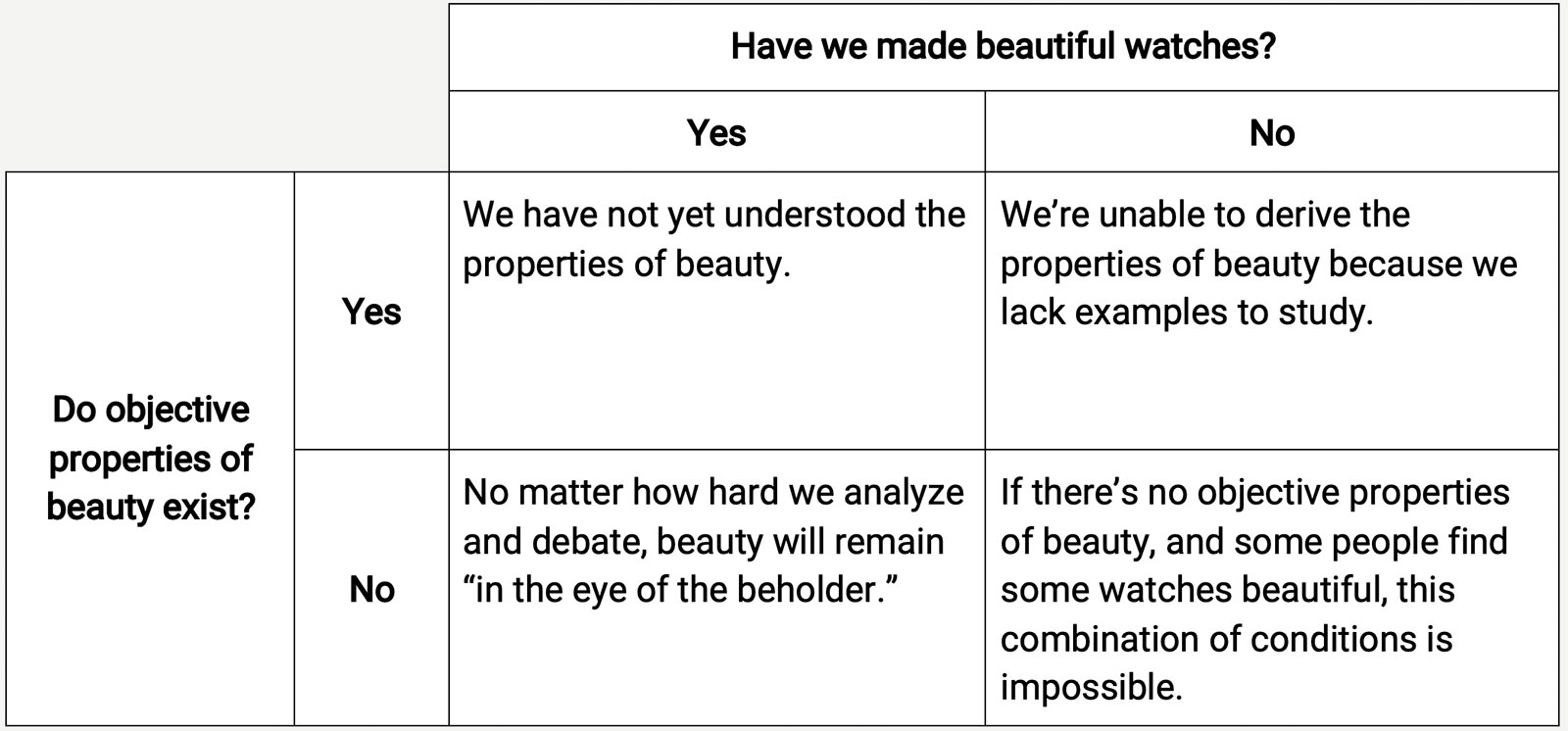

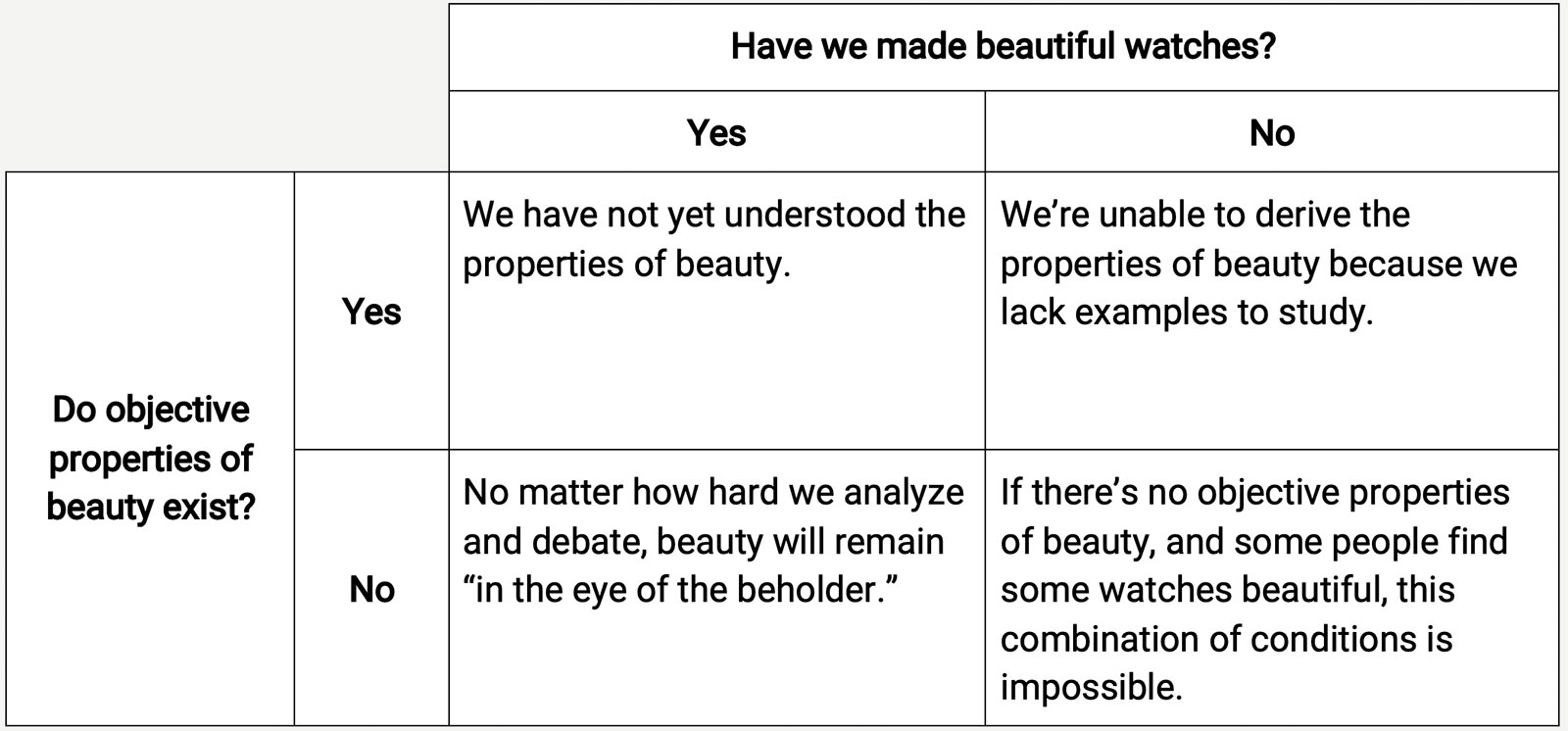

Whether an objective standard exists or not, I believe there are three possible realities, which I’ve summarised in this table:

Personally, I’m doubtful that an objective standard of beauty exists. If it did, I think we would have discovered it by now. After all, we discovered the properties of prime numbers over 2,300 years ago. I also find some watches beautiful, which by a simple process of elimination means that I must accept, even if grudgingly, that beauty exists only in the eye of the beholder. Of course, I remain openminded to the possibility that an objective standard does exist, and is just waiting to be discovered.

Trade-offs and “better”

Surely, if there’s one aspect of watchmaking that lends itself to objective assessment, it’s the movement. After all, watch movements are machines that operate based on quantifiable scientific principles, and we can conclusively measure things like rate and isochronism. These characteristics exist independently from individual subjectivity.

But even here, we will struggle to come up with a set of universal rules for determining whether one watch, or watch movement, is better than another. The problem stems from the fact that every watch movement is the result of dozens of trade-offs and compromises. And with each compromise, the definition of “better” becomes harder to pin down.

For example, one key trade-off watchmakers always have to face is balancing the power reserve with the power of the oscillator. Increasing one will decrease the other, and ideally you want both to be as high as possible. Is one of these trade-offs better? And if so, for whom? This is just one of many such trade-offs that exist in the design and construction of movements.

These conundrums cause collectors to sort themselves into different camps depending on their individual philosophies and preferences. Some prefer watches that favour a long power reserve for the sake of convenience (as long as timekeeping is kept to a reasonable standard), while others prefer movements that allocate more energy to the regulating organ, even if the difference is only discernible with a timing machine.

Perhaps it’s not a matter of one being better than the other, and it’s simply a matter of horses for courses. Either way, a clear-cut universal definition of “better” remains elusive, even in the most likely corner.

What is a watch, if not a timekeeper?

If you’re into mechanical watches in 2020, you’ve probably accepted the premise that modern watchmaking is about more than just accuracy.

Not so long ago, watches were often the timekeepers-of-record not just for daily life, but also for major sporting events and scientific exploration. With reputations, and sometimes even lives, on the line, chronometric precision and reliability truly mattered. As David S. Landes so eloquently put it in his excellent book on the history of measuring time, Revolution in Time, “… it has always been the rule that the quality of [a watch] is a function of [its] precision.”

Artefacts from a simpler time: the observatory-certified chronographs that once timed the Tour de France

But as we all know, quartz technology came along and made the sprung-balance completely obsolete. Today, Olympians and astronauts require greater precision than is possible from a mechanical timekeeper.

As a result, the mechanical watch was gradually reimagined as a luxury good and elevated from its status as a lowly appliance. This emergent freedom gave watchmakers creative license to express the wide-ranging visions of horology that characterise the luxury watch industry of today.

This evolution is material to the question of objectivity; should quantifiable performance standards apply to a machine that exists primarily as art? Personally, I believe that any fine watch must, out of respect for horological tradition, be built and adjusted to keep good time. But even I must recognise this for what it is – a subjective judgement.

The Ferdinand Berthoud FB-RE.FC, a theatre of chronometric drama

The freedom of subjectivity

I also think it’s worth questioning whether an objective standard is even desirable. For a moment, imagine a world where we could truly say that one watch is objectively better than another. In such a world, would there be room for connoisseurship? I don’t think there would be.

Subjectivity allows space for passionate opinions and debate, and is part of what accounts for the growth of the collector community over the past 30 years. In my view, the process of learning to make and refine subjective judgements is part of what makes this pastime so enjoyable.

I’ve always thought of myself as an objective and analytical person when it comes to watches. But while writing this article, I realised that a lot of the quasi-objective criteria that I use to judge watches are, in fact, almost entirely subjective. Recognition of this fact can help make each of us more empathetic towards the beliefs and tastes of other collectors. It’s helped me open my mind to new perspectives and made me a little less dismissive of certain watches that I’ve always believed were a waste of my time.

Acceptance of the subjectivity inherent in watch collecting does not mean conceding that all watches are equally good. On the contrary, subjectivity is what creates room for us to argue that some watches are better than others. The more we learn and refine our sensibilities, the more articulately we are able to justify our preferences, however subjective they may be, for certain watches over others.

Back to top.