When Accuracy Mattered – Part III: The Triumph of Brands Over Watchmaking

The curtain comes down on chronometer trials.

The demise of chronometry competitions last year – when the final edition of Concours International de Chronométrie took place – finally killed the dangerous heresy that a watch is a practical instrument that should be trusted to show the correct time. With the elimination of the last scientific and independent assessment of a watch’s worth, the cult of haute horlogerie comes into its own, reinforcing its definition of a watch as an emotional product born of passion, tradition and prestige.

Trials to see who can produce the most precise, accurate and reliable watch originated in Geneva in 1879, when the head of its observatory, Professor Emile Plantamour, devised a testing routine that rated watches in the various positions and temperatures encountered in everyday wear. Observatories soon became the influencers of the pocket-watch age, determining the legitimacy and worth of luxury timepieces. American magnates like James Ward Packard, Henry Graves Jr and Pierpont Morgan secured the most highly rated pieces.

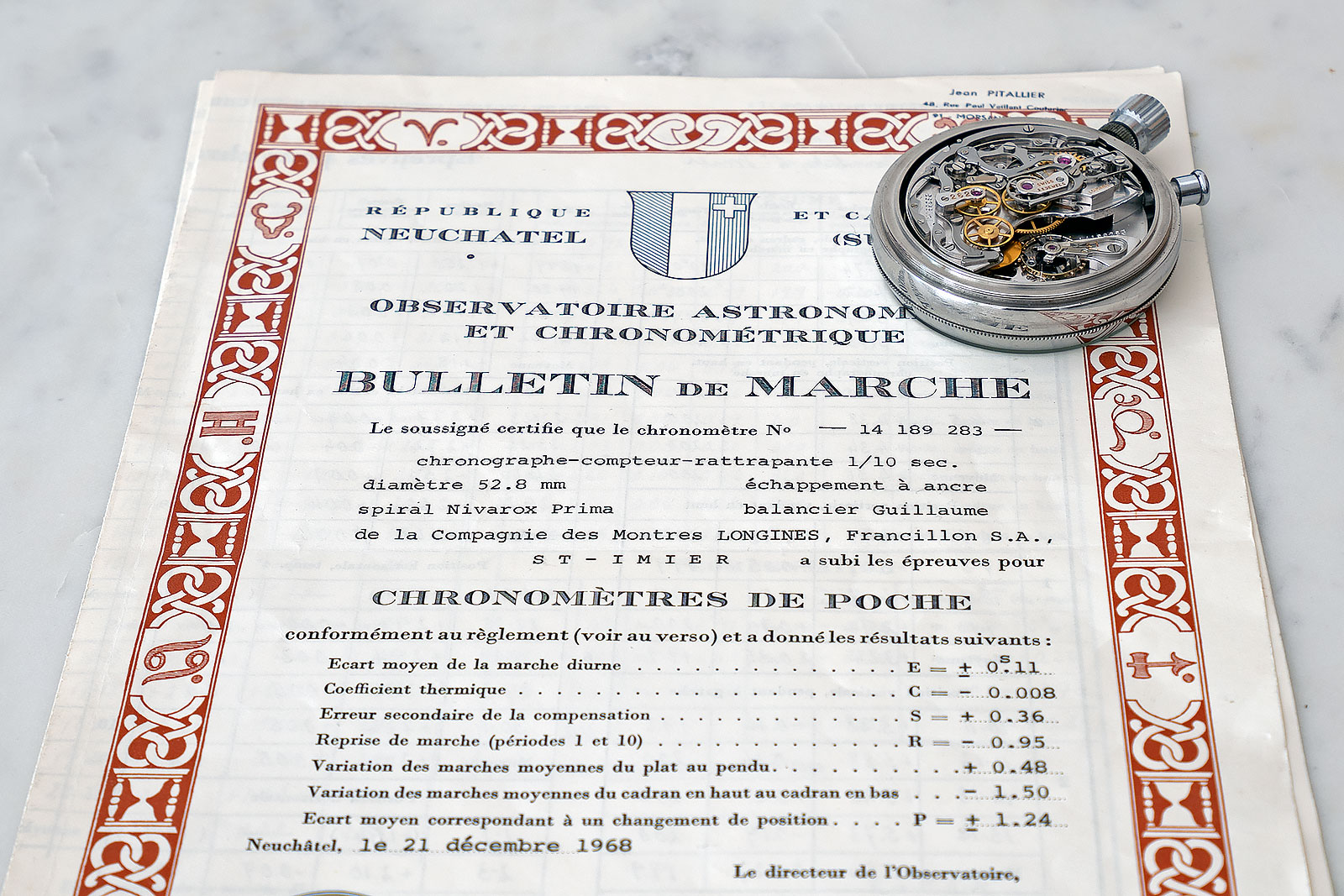

A Longines split-seconds chronograph pocket watch that was tested at the Neuchatel Observatory in 1968; this particular example once belong to Jean Pitallier, the former president of the French Cycling Federation (FFC)

Despite the advent of wristwatches, the Neuchatel Observatory kept the competitions alive until 1968 when Japanese entrants swept the board. In 1972, deputation of Swiss watch brand executive petitioned the Neuchâtel government minister René Meylan to exclude non-European makers — the Japanese — from Swiss rating institutes. When this was denied, Swiss watchmakers boycotted the trials. A year later, the Contrôle Officiel Suisse des Chronomètres (COSC) was set up, consolidating all Swiss watch testing while imposing less stringent standards. COSC remains the dominant industry testing body today.

The Neuchatel Observatory continued to rate wristwatches and publish results until 1976, but it was always a struggle against the tide. Quartz watches had outclassed mechanical watches in accuracy, precision and reliability. Continuing the competitions seemed pointless. Quartz movements had also freed the Swiss mechanical watch from the chains of accuracy, allowing it to be redefined as a pure luxury product. With its world monopoly of luxury watches, Swiss watchmaking was on a roll.

The wrong kind of competition

Then in 2009, the small but venerable horological museum of Le Locle unexpectedly put back the clock 35 years by announcing it would celebrate its 150th anniversary by organising the first timing contest of the 21st century, the Concours International de Chronométrie. The Musée d’Horlogerie du Locle invited brands, movement manufacturers, schools and private individuals to enter a points-based timing competition, designed to test the rate and reliability of their watches.

It seemed a crazy idea. The Swiss watch industry, a de facto cartel, collectively abhors competition, with one exception: the rivalry to command the highest retail prices. Grading watches according to their performance would upset the established hierarchy of brands, familiar to any modern watch enthusiast. Simply put, among luxury brands, the established double-barrelled names, such as Vacheron Constantin, Audemars Piguet or Jaeger-LeCoultre, look up to Patek Philippe. Among the more popular and practical watches, Omega and Breitling dutifully line up behind Rolex, while jewellery brands kowtow to Cartier.

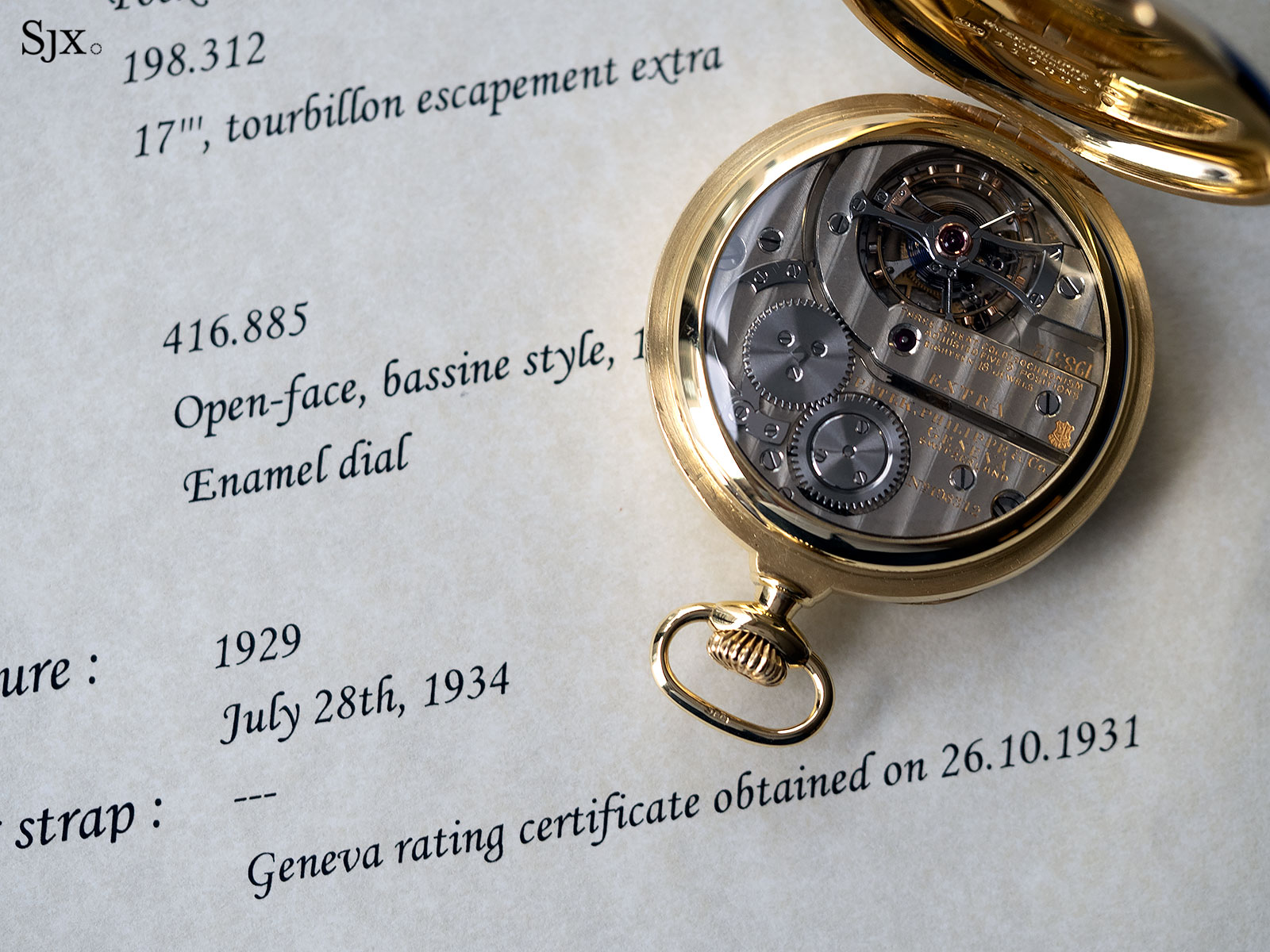

A Patek Philippe tourbillon pocket watch that competed in the Geneva Observatory trials of 1931

The Chronometrie 2009 trial comprised three 16-day COSC rating tests with the watches cased up, conducted according to the ISO 3159 standard in different laboratories. Between the second and third tests, the watches were subjected to shocks and magnetic fields. The tests essentially determine the rate of the watch: how much it gains or loses a day (accuracy), and the constancy of that rate (precision) in different temperatures and static positions. Any watch outside the tolerances in any of the seven criteria in each of the three tests is eliminated.

Threat to prestige

Entering the competition brought huge risks – a single winner, everyone else the loser. In an industry where half-a-dozen brands claim the thinnest, most complicated, most unique, best finished, deepest diving, or even most precise watch with equal illegitimacy, such an objective and independent test seemed quite unnecessary.

Most importantly, failing to win would be fatal the brand’s image, especially if beaten by a brand of lower caste. Winning would be equally embarrassing. It would confuse consumers who would start to demand accuracy. And a customer who expects accuracy is a perpetually dissatisfied customer, because accuracy is impossible to deliver. All watches go either fast or slow.

Chronometrie 2009 looked like mission impossible, but the organisers thought they knew how to allay the brands’ worst fears. Only the winner would be announced in each of the categories. The results would be kept in bank-like secrecy. Japanese and Americans would be excluded. Publicity would be kept to the minimum. No press trips or freebies.

To confuse any foreign journalists who might be interested, the organiser’s English-language press release stated: “Our goal is to relaunch the interest of the chronometry in the contemporary watch-making while leading an innovative experience experiment, it to take up with a know-how by adapting it to the modern techniques of control of watches presented to the competition.” (sic.)

The organisers also knew that if they attracted one really prestigious brand they could rely on the herd instinct of the watch industry for others to join it. But A-list brands — Patek Philippe, Vacheron Constantin, Breguet, Rolex, Omega — as well as others who felt too big to fail, wisely stayed away.

The tourbillon shock

Rashly, Jaeger-LeCoultre agreed to take part. That brought in Audemars Piguet, Chopard and 13 other contestants, notably, Zenith, F.P. Journe, and Greubel Forsey. Timidly, Chronometrie 2009 got underway. It took four more editions before the competition was killed.

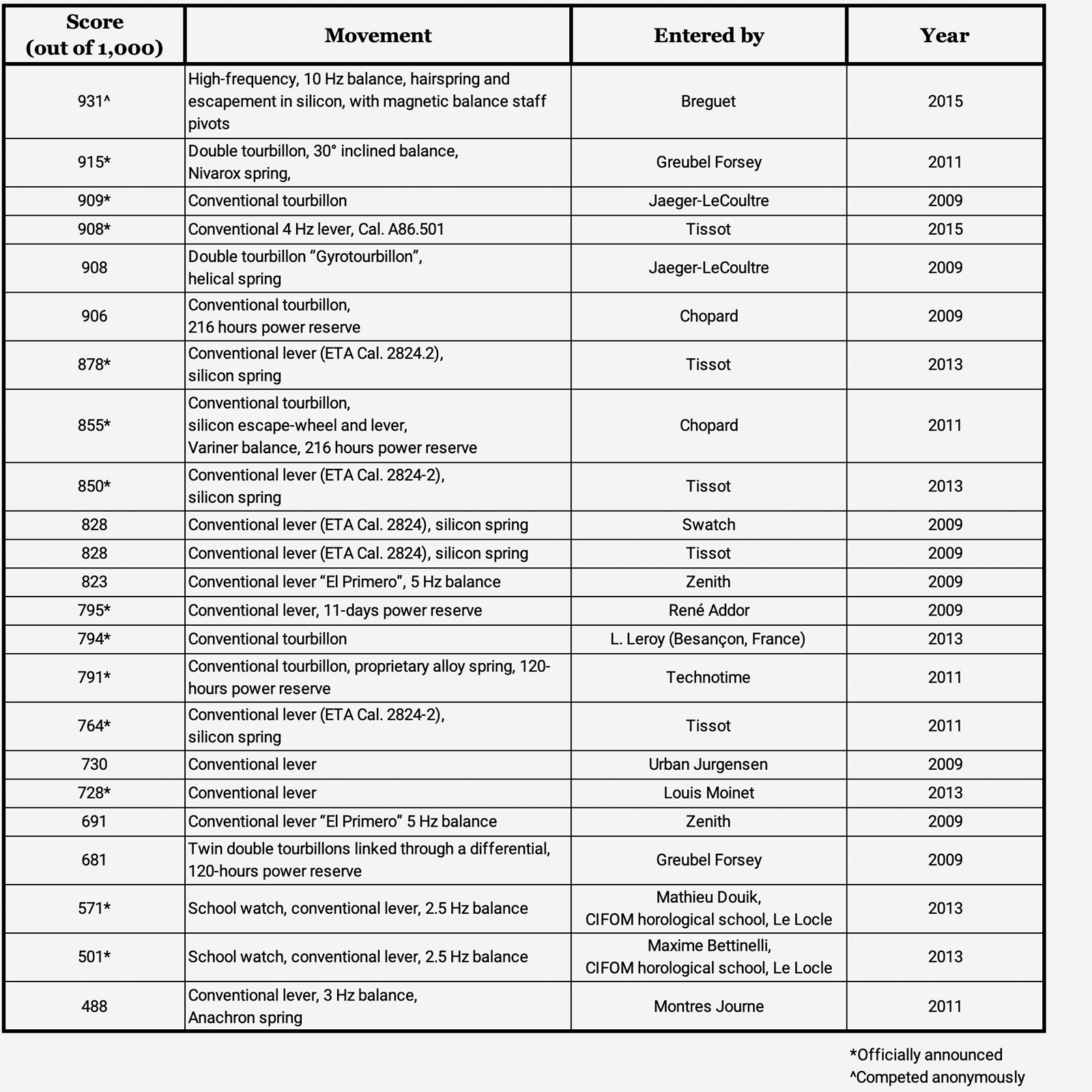

The first two competitions produced a surprise: tourbillon watches won hands down.

In Chronometrie 2009, Jaeger-LeCoultre’s Master Tourbillon came first with an astonishing 909 points out of a thousand. In the conviviality of the prize-giving, it soon emerged that Jaeger-LeCoultre had also come second by just one point (908) with its extremely elaborate, multi-axis Gyrotourbillon. And Mr Karl-Friedrich Scheufele graciously confirmed the leak that Chopard’s LUC 16/1906 tourbillon had come third with 906 points. (The leaks went on until this reporter was able rank all the contestants.)

The revelation that the tourbillon actually enhanced the performance of a watch came as a shock. Shifting the tourbillon’s appeal from the emotional to the rational would demolish the reputation of a gadget that puts tens of thousands of francs on the price of a watch. Quartz had made accuracy cheap; the tourbillon was tainted with cheapness.

The Gyrotourbillon, an example of which scored 908 points at Chronometrie 2009

The shame of winning

The culprits were quick to limit the damage. Jaeger-LeCoultre’s top management distanced itself from the prize-giving, preferring the glamour of a polo tournament in Argentina to wintry Le Locle. Five days later the company buried the news in an 800-word press release of the kind nobody reads. It was a complete success. Not one headline announced that Jaeger-LeCoultre had built the world’s most accurate and precise mechanical wristwatch.

Those familiar with the Greubel Forsey brand would know that they produce some of the most expensive wrist gadgetry. What they probably don’t know is that they have built the most accurate and precise wristwatch of modern times. Greubel Forsey were too modest to announce that their double tourbillon with a 30° inclined balance on a Nivarox spring had dethroned Jaeger-LeCoultre to set an unbeaten record of 915 points in 2011.

The Greubel Forsey Double Tourbillon 30°

Chronometrie 2011 attracted 18 contestants, many of them manufacturers of tractor designs — mass-produced 4 Hz workhorses. Only five of the entrants survived — a massive failure rate of 72% compared with 37.5% in the first competition.

The organisers tried to save the situation by allowing brands to compete anonymously in 2013, and continue the test if they failed one of the hurdles. The results of the unclassified contestants would be kept secret. As a further incentive, each brand could enter three identical watches to increase their chances of mounting the podium.

The last straw

But the expensive brands began to drop out as their worst fears were realised. Humble Tissot watches started to sweep the boards in the 2013 event, taking the first two places with 878 and 850 points, beating a Leroy tourbillon to a distant third. Tissot was taking the contest seriously, developing competition watches based on ETA 2824 series calibres with silicon springs. Chronometrie increasingly became a testing ground for 4 Hz tractors, and Tissot dominated the contest.

The next event in 2015 marked the triumph of Tissot. Only 10 brands entered, three anonymously and 18 school watches. The school watches, with old-fashioned 2.5 Hz movements, all failed.

Tissot came first, second and third in the conventional watch category and first among the chronographs. Its winning watch, with an ETA derived cal. A86.501 and 4 Hz lever escapement, scored an astounding 908 points — equal in performance to the Jaeger-LeCoultre Gyrotourbillon, but several hundred thousand dollars apart in status.

Most intriguing was the top-performing anonymous entry that scored 931 points, still the all-time high for Chronometrie. Revealed by industry sources to be the Breguet cal. 574DR with magnetic balance staff pivots, its success proved that materials science and engineering matter more than haute horlogerie mystique.

It was too much to bear. The 2015 event turned out to be the last Chronometrie competition. The 2017 contest was postponed for want of support.

The prize ceremony in 2015. Photo – Concours International de Chronométrie

The organisers tried to revive it in 2019, rewriting the rules so as to eliminate any possible damage to brand prestige. Points and rankings were abolished. The watches would be titled “excellent” (800 to 900 points) or “exceptional” (> 900 points). Watches that survived the first COSC test were given a certificate. Competitors were to be anonymous, except for the award winners. Only Swiss made watches were allowed — excluding the one French brand, L. Leroy, that had made Chronometrie “international.”

Five watches entered the competition. Only one survived the elimination round and went on to compete — anonymously.

The press release announcing the end of the competition dryly noted “the 2019 harvest of the participating watches was particularly modest”. There was no point in holding an awards ceremony. Instead, the organisers held a “vibrant celebration of Swiss precision watchmaking” consisting of a round-table discussion and an online magazine that glossed over the debacle.

For parts I and II of When Accuracy Mattered, click here.

Addendum: A hierarchy of the most accurate, precise and reliable wristwatches

Although brand and marketing communications managers looked upon the Chronometrie competitions with fear and horror, the people who actually make the watches were generally keen to compete. It was from the latter sources that the rankings below could be compiled.

Addition September 24, 2020: Text amended to clarify that trials at the Neuchatel Observatory ended in 1968, but the observatory continued to test watches until 1976. And addition of the fact that the Breguet cal. 574DR scored 931 points in 2015, making it the all-time high scorer for the contest.

Back to top.