In-Depth: Greubel Forsey Tourbillon 24 Secondes Architecture

Three dimensional, intricate, and impressive.

A hallmark of Greubel Forsey’s unique brand of watchmaking is its inclined, high-speed tourbillon that completes two and a half revolutions per minute. In fact, it was the first tourbillon by Greubel Forsey (GF) when the brand made its debut in 2004.

Almost two decades on, the brand’s quintessential regulator has been installed in something entirely different with the Tourbillon 24 Secondes Architecture. While the inclined tourbillon remains, the Architecture is almost entirely new as a watch, comprising a brand-new case design containing a reconstructed movement – that is a tangible realisation of architecture – which together form a cohesive whole.

Initial thoughts

The Architecture may seem like just another GF sports watch at first sight, so one might dismiss it as being merely a repurposed movement modified to fit into the brand’s bestselling sports watch case. But it is more than that.

The inclined tourbillon has been transformed into something refreshingly novel where the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. And it manages to be novel despite high-end sports watches being increasingly common. In short, it’s one of the most notable watches in the GF line-up.

Despite the familiar mechanics of the tourbillon, the details of the movement have been comprehensively reimagined to emphasise the brand’s distinctive approach to movement construction, one that prizes three-dimensionality in design matched with impeccable finishing.

This incremental improvement that builds on the original inclined-tourbillon calibre is crucial in setting the Architecture apart from all of its predecessors. In fact, the Architecture is arguably the most impressive version of the movement to date, a quality that is especially apparent when the watch is examined up close.

One of the defining characteristics of the Architecture is the design – of both the movement and case – which is ultra-modern like GF’s other sports watches, but takes the visual experience a step further with an increased depth of field. Put simply, there is more of the movement visible from every angle than before.

To achieve that, the movement has been thoroughly skeletonised, while many key parts are deliberately tall, creating a sense of depth while offering a spectacular view in profile thanks to the sapphire case middle. Like many GF watches, the Architecture is very thick, but it utilises all of the height for maximum visual impact.

And importantly – this is a Greubel Forsey after all – the movement finishing is excellent. The top-class decoration boosts the appeal of the beautifully constructed movement exponentially. The exaggerated, structural bridges are a highlight: each has been mirrored polished on both flat and gently curved surfaces.

To accommodate all of that, the case is necessarily massive at almost 17 mm high with a bezel that’s 45 mm in diameter. But like GF’s other sports watches, the smartly designed case minimises the perceived size of the watch. It still looks large on the wrist, but not enormous and unwieldy.

The streamlined design also has surprisingly good ergonomics for a watch of this size. The case is slightly curved while the strap integrates into short lugs, so it sits well even on smaller wristwatches. That said, there’s a nit to pick here: the double-fold clasp does feel bulky and not quite as sleek as the watch itself.

Architectural exterior

Extra-large yet sleekly formed, the curvaceous case resembles earlier GF sports models at a distance, but immediately becomes distinctive when viewed from the side. Both the lugs and and flanks have been extensively reworked, setting it apart from the standard sports watch case. The result is a case that melds the sports watch concept with the mechanical theme of an exposed movement.

The Architecture case is unorthodox in all respects. In fact, it’s more accurately described as a clear sapphire ring sandwiched between the titanium bezel and case back. And the lugs are “floating” – they sit a tiny, indiscernible distance away from the sapphire ring and are instead a single piece with the case back.

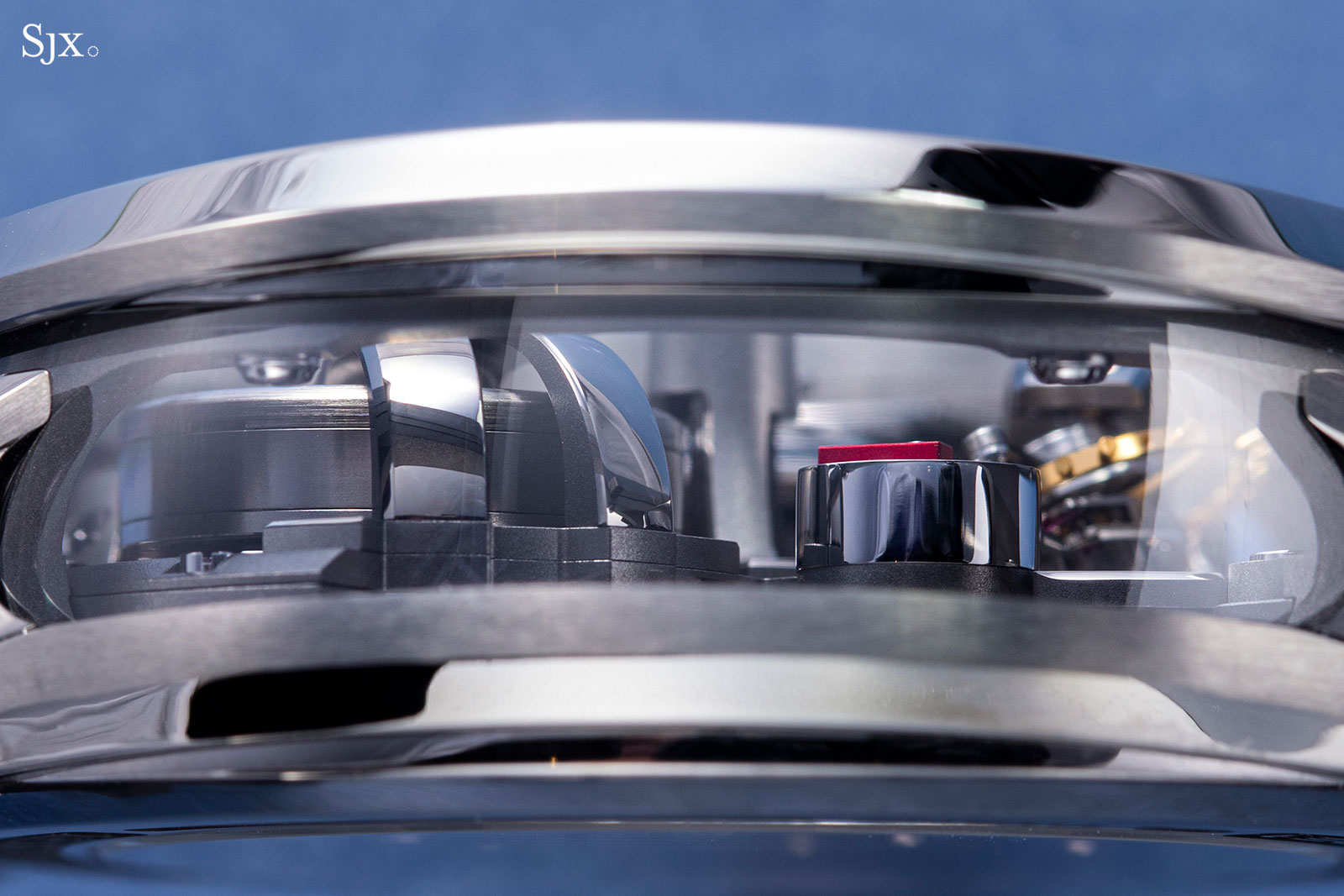

The sapphire case middle offers a view into the movement…

From both sides

While the brand has utilised sapphire windows on its cases before, the Architecture has the sapphire window encapsulate the perimeter of the movement, putting it second amongst GF watches in terms of transparency after the Double Balancier in sapphire.

But even the all-sapphire Double Balancier is arguably less interesting compared to the Architecture, as the latter’s sapphire case middle is entirely round. This allows plenty of light to enter from multiple angles, allowing for a brighter view of the dial components.

And of course the movement is fully visible from a side, a crucial perspective the design because the movement has been developed from ground up to look tall, spacious, and architectural. In fact, the view through the side of the case is akin to an urban landscape of densely-spaced buildings, but made even more impressive in miniature.

The barrel is visible at far left, while the column holding the red seconds hand is on the right

In principle, the most important aperture is at six o’clock, revealing the high-speed tourbillon within. Due to the tall case, the tourbillon can be admired even when on the wrist – a view further enhanced by the abundance of light entering the case which allows the polished bevels of the cage to subtly gleam as makes its 24 second rotation. Add to that the incline balance wheel and the tourbillon is certainly intriguing to observe.

But there is an argument to be made that the power reserve mechanism visible at two o’clock is equally intriguing – that will be explored in detail below.

The tourbillon seen through the six o’clock window

To further emphasise the complexity of the case, the bezel and front crystal aren’t flat and round as on a conventional watch. Instead, they resemble a riding saddle, with a double curvature and oval shape, which have become a hallmark of GF sports watches.

First seen on the GMT Sport, the curved oval has since been refined on the Architecture such that it is less pronounced, resulting in a proportional and balanced aesthetic that is pleasing to the eyes while still allowing plenty of light onto the open-worked dial.

And in typical GF fashion, the inner step of the bezel is laser engraved with themes core to the brand’s philosophy, albeit in a more discreet manner than in several past models due to the smaller volume of text – there are only nine words on the bezel – arguably a step in the right direction.

Impressive as the case is, perhaps one criticism can be made: the bezel is secured to the case back via screws that fasten to the inner walls of the case. These screws are clearly visible from the sapphire windows on each side of the case, a minor distraction when viewing the more important components within.

Because of the streamlined form of the case, the lugs are integral to the design. They have been designed expressly to showcase the strong lines that define the case. Despite not being connected to the case middle, the lugs flow almost seamlessly into the case.

Compared with GF’s past watches, the Architecture’s lugs are more complicated in terms of design and finish. The tops of the lugs are distinctly flat planes with a brushed finish, which contrasts them with the curved, polished flanks. Adorned with a mirrored bevel, the flat top surfaces of the lugs are mechanical and aggressive while their sides offer a fluid and organic appearance.

The sides of each lug have been fluted to create a deep, polished channel flanked by brushed borders – it’s a good combination because the mirrored surface becomes less obvious due to its concavity. And despite the highly modern style of the watch, details like the lugs calls to mind the fluid lines of 1930s race cars.

The “floating” lugs sit an indiscernible distance from the sapphire ring

To top it off, the lugs have been designed for good ergonomics, hence the taper downward towards the strap.

Wearability is also aided by the buckle. The monolithic case is balanced with an equally hefty folding clasp, which is similar to that found on other GF watches, making it seem almost ordinary in comparison to the delicately complex case. Though the finishing of the clasp is impeccable, it doesn’t have quite the same streamlined feel as the case.

A bracelet is not available for the Architecture yet, but I am certain one will be, as is the case for the other GF sports watches. With the typical GF bracelet in titanium priced around US$40,000, it will be an expensive option, but will no doubt enhance the flowing lines of the case.

Deconstructing the movement

While the case construction is impressive, it is undoubtedly the movement that is the most tangible realisation of the GF philosophy.

The Architecture’s movement appears familiar at a glance, for good reason since it is one of a number of variants of a base calibre. But each variant has a gear train rearranged to fit each model’s overall aesthetic.

Notably, its closest relative is the Double Tourbillon Technique that shares many similar elements, but as the name implies, the Double Tourbillon Technique has a more complex, double-axis tourbillon and more mainsprings, four of them to be exact, instead of the three in the Architecture.

GF movements are often unconventional in terms of layout and typically asymmetric, reflecting the design ethos. As a result, each calibre is almost a tiny horological puzzle when it comes to understanding the basics of the movement.

That said, GF most movements are fundamentally conventional at their core, so they can be figured out after some contemplation, as is the case with the Architecture. Knowing how the Architecture functions does demystify its intricate-looking mechanics, which perhaps diminishes some of its esoteric charm, but it doesn’t take away from the fact that the movement is a visual treat.

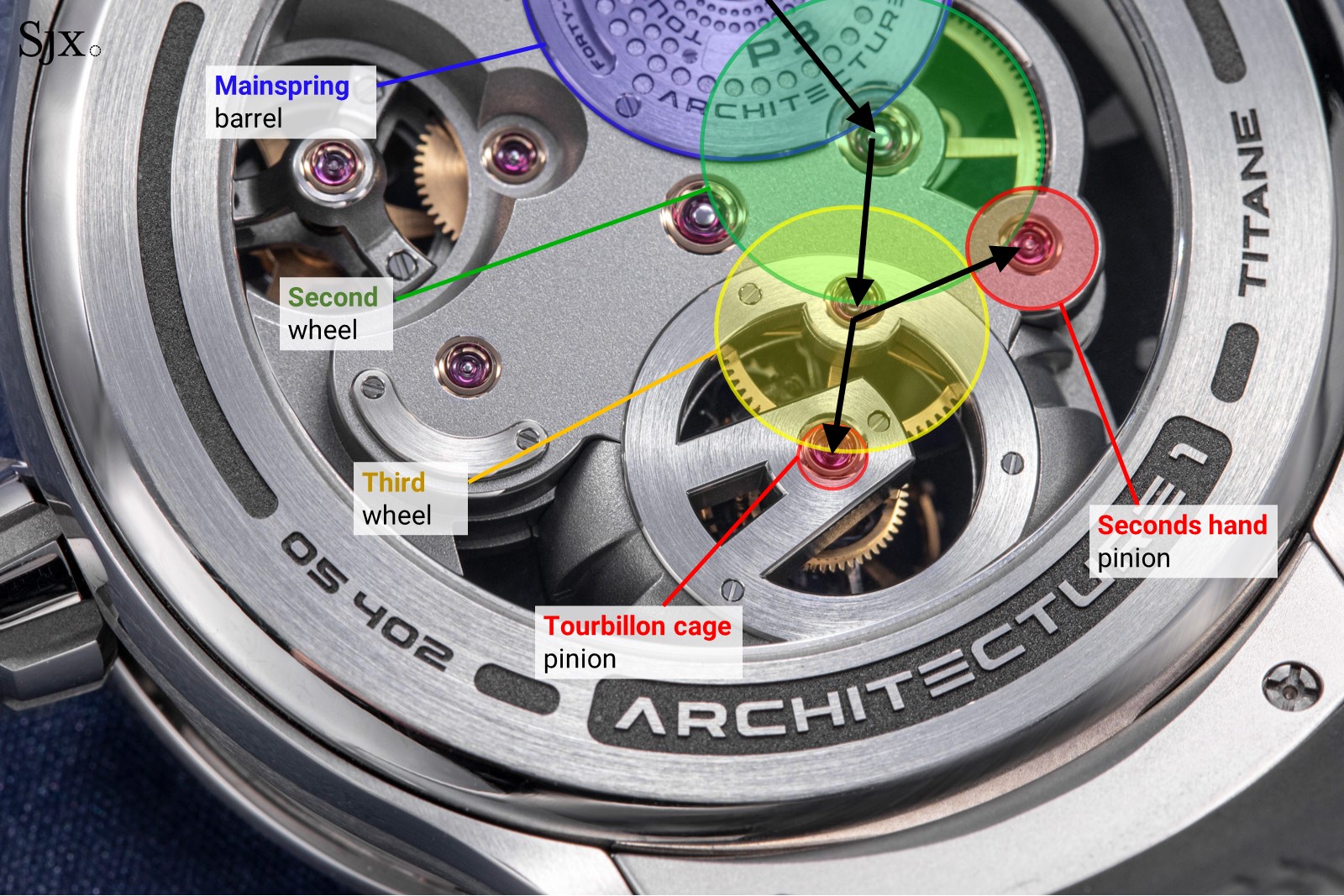

The power flow in the going train

At its core, the Architecture has a straightforward going train that starts from the barrel, then progresses to the second and third wheel, which drives the tourbillon cage.

Additionally, the third wheel drives an auxiliary pinion, which powers the seconds hand visible on the dial side. One notable quirk is that the gear ratio between the third wheel and tourbillon cage is 2.5 times larger than the ratio between the third wheel and the seconds pinion, explaining how the tourbillon cage rotates once every 24 seconds (since 60 seconds divided by 2.5 is 24).

Note the seconds hand pinion has 2.5 times more teeth than the tourbillon cage pinion

The seconds hand is a necessity since the tourbillon makes a revolution every 24 seconds, instead of the conventional one-minute rotation of a traditional tourbillon

The regulator

The tourbillon itself is of the brand’s traditional design and can be found on other GF watches with the same tourbillon, such as the Tourbillon 24 Seconds Vision. It rotates the balance wheel once every 24 seconds at an incline of 25° from the horizontal.

In theory, the incline allows the balance wheel to sequentially occupy across more positions in three-dimensions, which further averages out the positional errors caused by gravity when compared to a conventional tourbillon that was conceived to constantly rotate the balance in a fixed, vertical position. However, timekeeping accuracy is more of an academic exercise than practical necessity in the realm of six-figure watches like this.

The inclined tourbillon with its two-armed cage

Made of lightweight titanium, the tourbillon cage is thin and shaped like a tuning fork, which further reduces its weight. The reason for the two-pronged end on one side of the cage is poising – it adds slightly more mass to counterbalance the weight of the escape wheel and pallet fork on the other end.

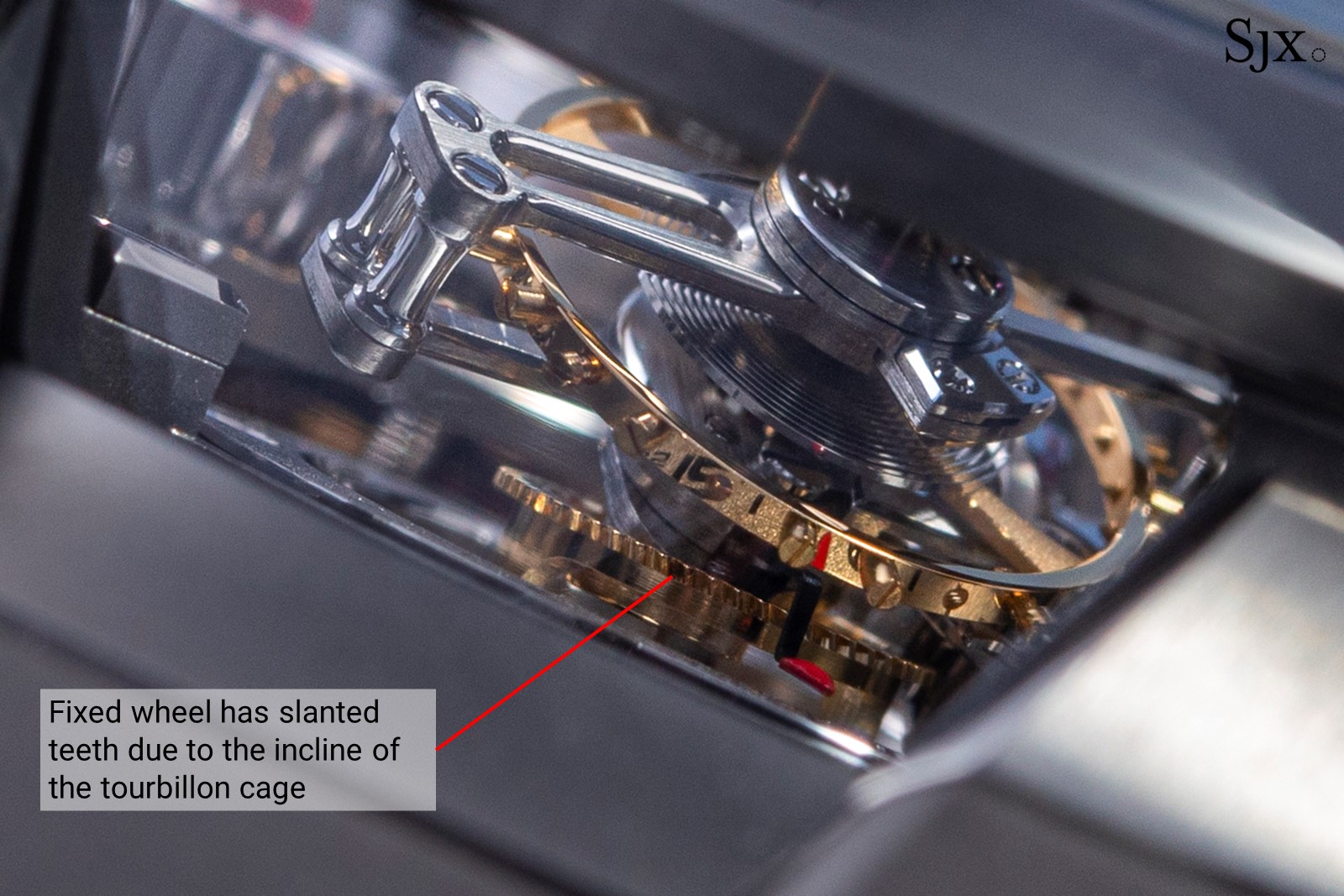

An interesting detail only true nerds will appreciate can be found within the tourbillon. As with all types of tourbillons, this has a fixed wheel that functions as the hub to rotate the escape wheel as it is dragged around by the tourbillon cage.

But because it is an inclined tourbillon while the fixed wheel sits parallel to the plane of the movement, both the fixed wheel and escape wheel pinion require teeth that are cut at an unconventional incline, something that is distinctly uncommon in watchmaking.

The tourbillon cage is finished with straight graining on the top and and anglage along the edges. It is finished in the manner typical of other GF models with the same 24-second tourbillon. That means it isn’t as elaborately executed as the higher-end double tourbillons that have black-polished, rounded arms and sharp corners within the anglage.

A nitpick here is that the tourbillon is simpler than the brand’s flagship, twin-axis Double Tourbillon, which is not only more complex mechanically but also has more complex finishing. But the 24-second tourbillon is perhaps more apt for a sports watch, especially one with a face as busy as the Architecture. Less is more in this case, as a simpler tourbillon does distract too much from the other visible movement components, of which there are many. And of course, the high-speed nature of the 24-second tourbillon and its resulting stability fit the concept of a sports-watch.

The low-key finishing of the tourbillon cage is made even more prominent when compared to the highly mirror-polished titanium arch that supports the cage

Arches, arches, all around

That is probably because the Architecture is not all about the tourbillon, but rather the architecture of the movement that is embodied by the five black-polished titanium bridges that support the major components.

At a glance the bridges appear arranged in a haphazard manner, which is paradoxically a nod to traditional watchmaking. Their positions are reminiscent of traditional pocket watch movements where the bridges are fixed to the base plate at seemingly arbitrary angles.

This seemingly chaotic layout, with all the bridges at different angles, ironically result in a coherent aesthetic, a feat few brands are able to pull off.

And the coherence of the design is enhanced by the fine finishing across all the components. The high level of decoration makes it clear that every part, no matter how small, was carefully conceived, so nothing seems like it was tacked on as an afterthought.

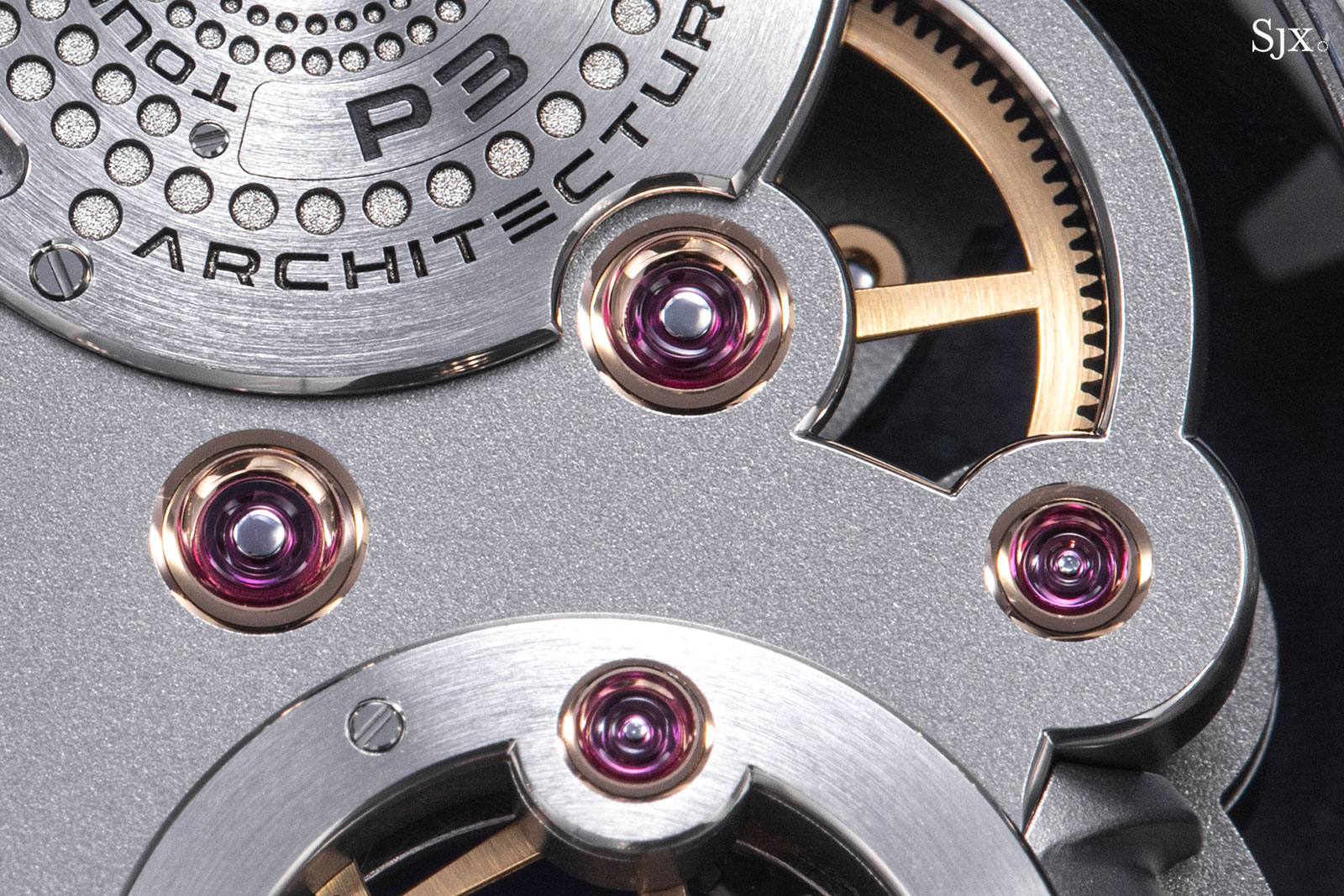

However, the Architecture goes a step beyond the usual high level of finishing GF is known for. The arched bridges are exceptionally well finished.

Each of the arches feature complex curved surfaces, yet still exhibit crisply uniform anglage along their edges that neither disrupt the curvature or reveal any hints of unevenness. Each bridges impressively manages to achieve a delicate balance and avoids looking either plain and flat or being over-polished to the point of being excessively rounded.

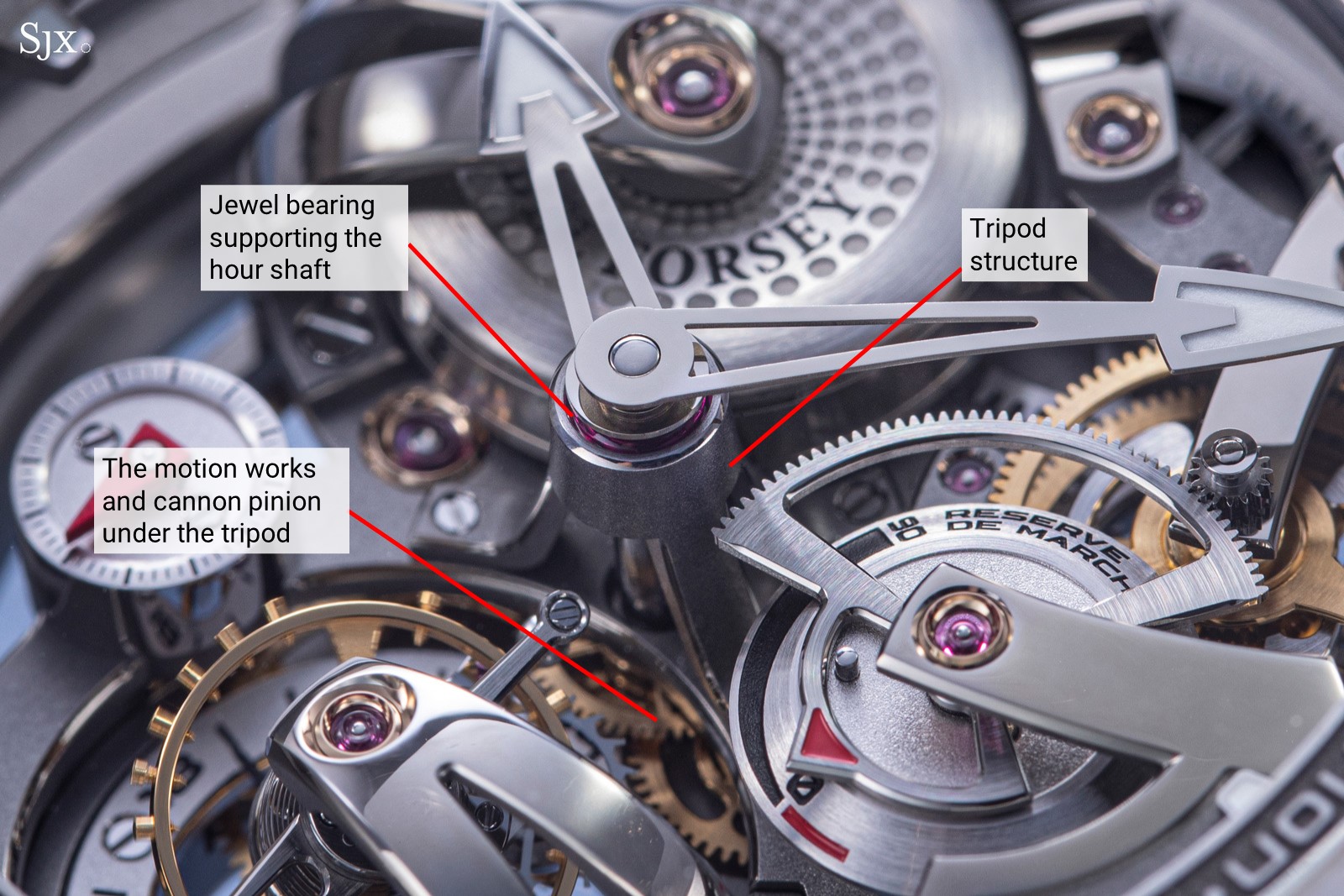

Amidst all the visual complexity on the front, the time is still displayed conventionally with central hour and minute hands. However, the hands are elevated by an impressively tall tripod, allowing them to clear the numerous raised components.

Because the hands are raised, they require an elongated pinion. That in turn calls for a jewelled bearing, visible within the tripod, so as to minimise the extra friction of the extended pinion.

And of course, the tripod itself is well finished – finely frosted across its surfaces, while having many edges with neatly rounded bevelling.

While majority of the movement is visible on the dial, that conversely means some parts are inevitably hidden. The keyless works and intermediate wheels are positioned deep inside the movement, under the power reserve mechanism. In other words, they sit under the main plate on the back.

A full-sized “diff”

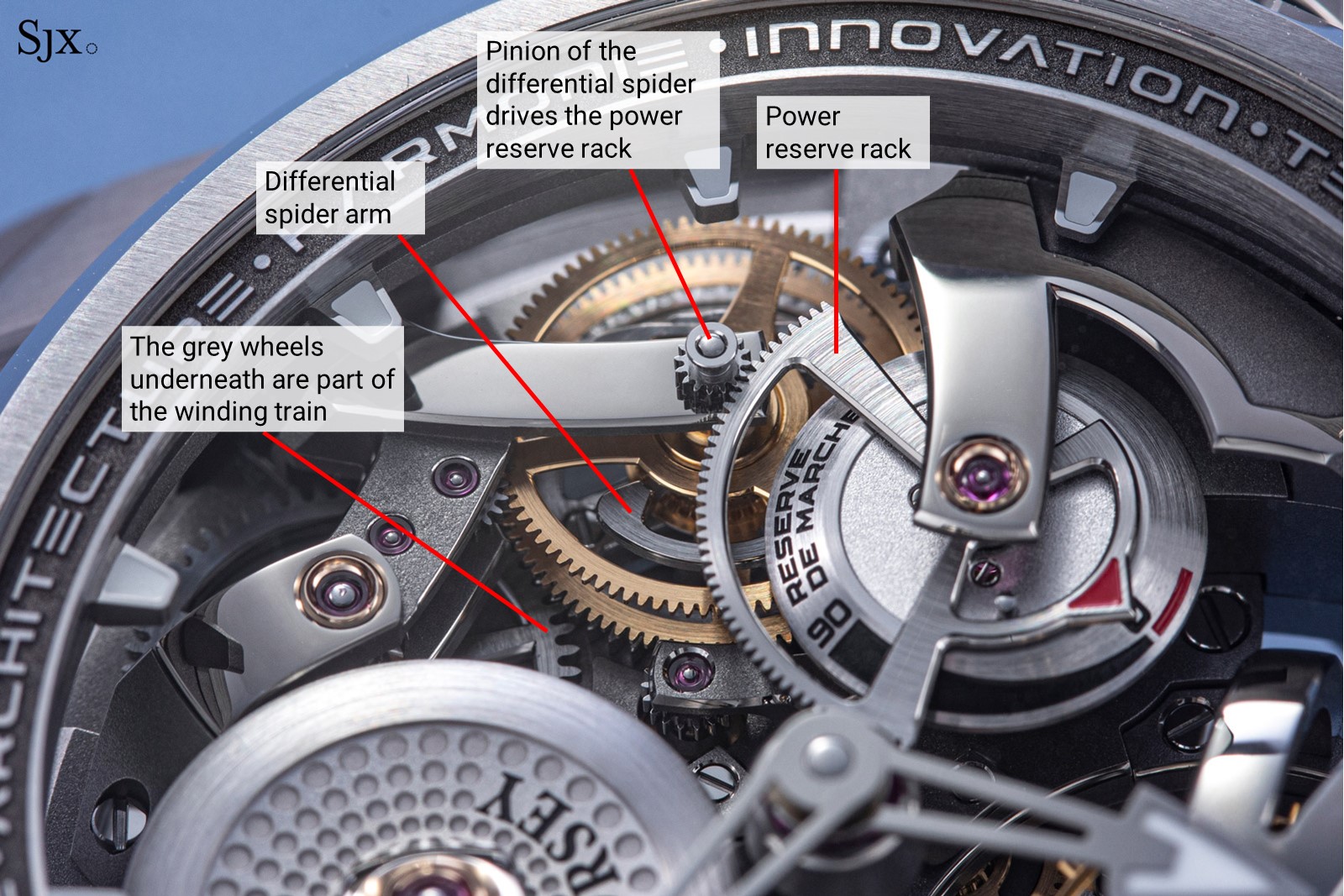

Besides the arched bridges and the tripod for the hands, another of the architectural highlights of the Architecture – no pun intended – is the exposed power reserve mechanism. While conventional in mechanical terms, the open-worked dial exposes the details of the mechanism, allowing the wearer to enjoy a visibly tangible interaction with the movement when winding it.

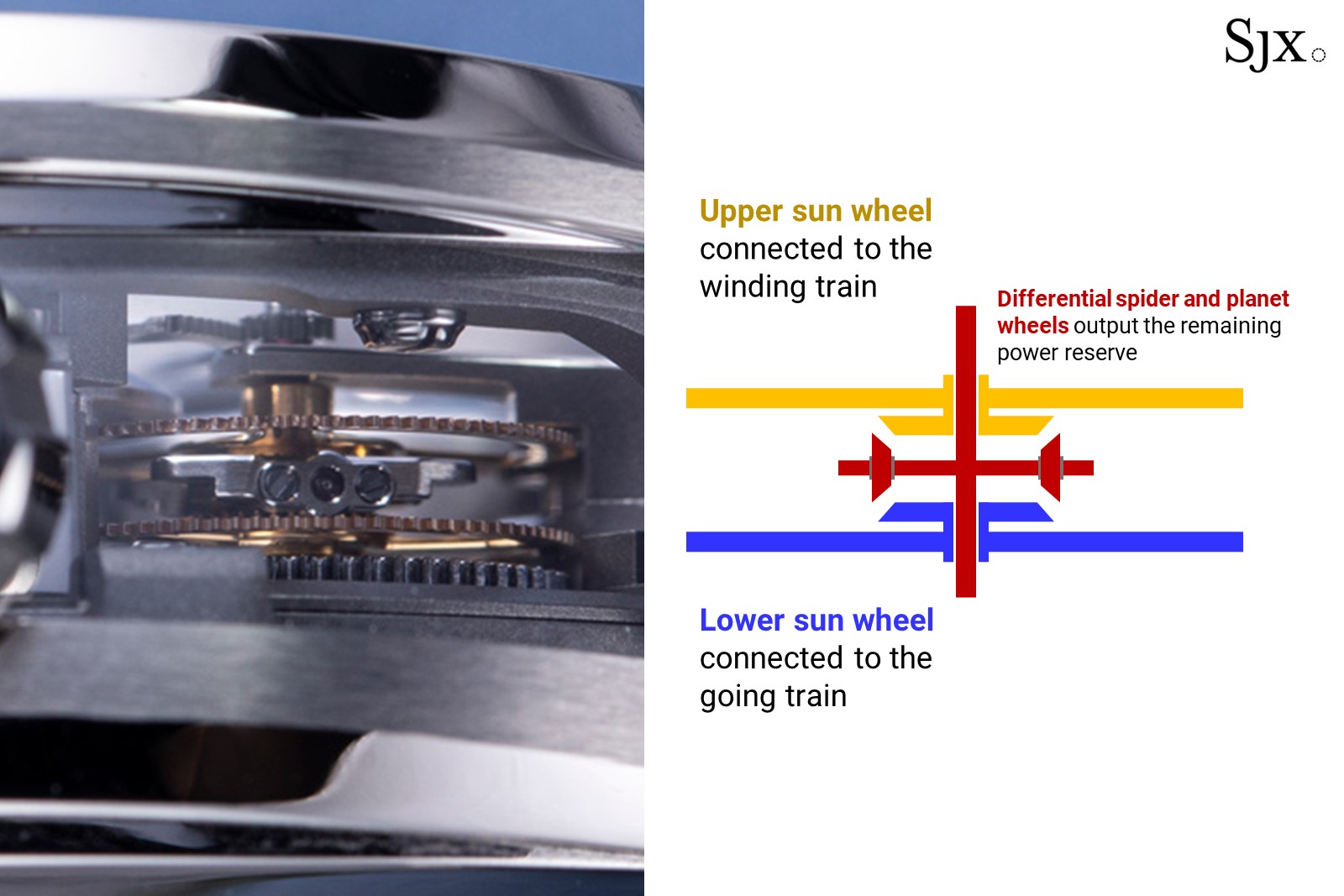

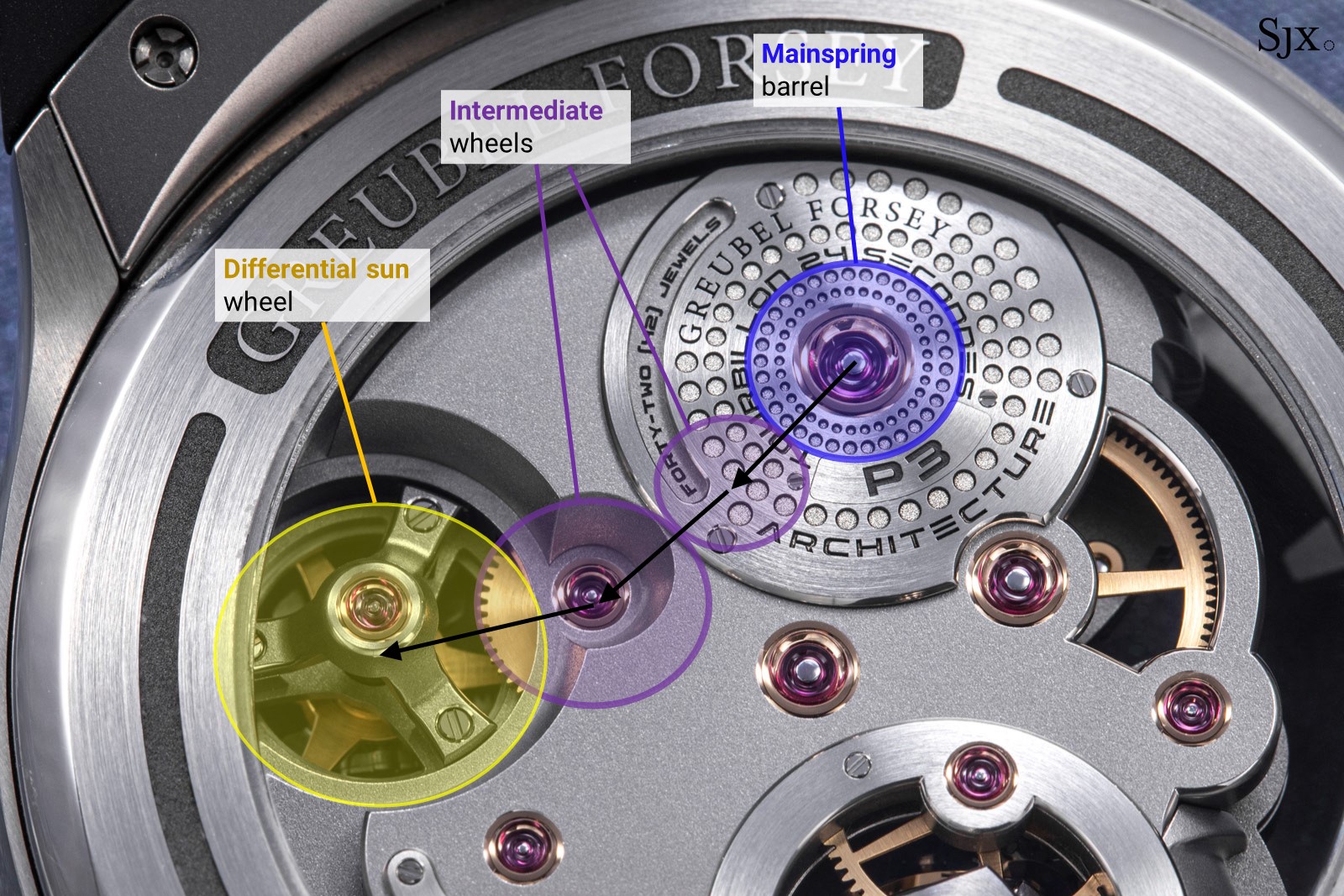

Especially notable is the use of a full-sized, spherical differential, which is made up of a spider gear and perpendicular planetary gears sandwiched between two sun wheels.

Also found in other GF movements with power reserve displays, this type of differential is similar to those found in automobile transmissions, but its size means it’s only used in watches that can accommodate the thickness. In comparison, conventional power reserve mechanisms used in thinner watches use flat planetary gears, which are less interesting visually but are usually hidden under the dial in any case.

A closeup of the differential with its two superimposed sun wheels in brass

The red indicator for the power reserve

The spherical differential in the Architecture is large and visually impressive, and can be seen in action – turning as the barrel is being wound – through the sapphire window next to the crown.

The exposed mechanism makes it easy to understand. The spider gear measures the rotational difference between two sun wheels; this difference rotates a pinion that then turns the power reserve indicator, which is a toothed rack that has a tiny red arrow on its edge to point to the state of wind.

The upper sun wheel is driven by the winding train, which is visible from the dial side, underneath the differential. As a result, the wearer enjoys an animated spectacle when the crown is turned to wind the watch – the winding wheels, barrel, spider gear, and power reserve rack rotate in unison.

Meanwhile, the lower sun wheel is continuously driven by the going train. While it is unfortunately hidden by the main plate, the sun wheel rotates at an imperceptibly slow rate as the mainspring unwinds, making it less of a priority in terms of aesthetics.

Notably, the GF Double Tourbillon 30° Technique in ceramic has a similar mechanism with clear sapphire bridges that fully reveal the movement trains.

The barrel containing three stacked mainsprings as seen from the dial

Geometric landscape

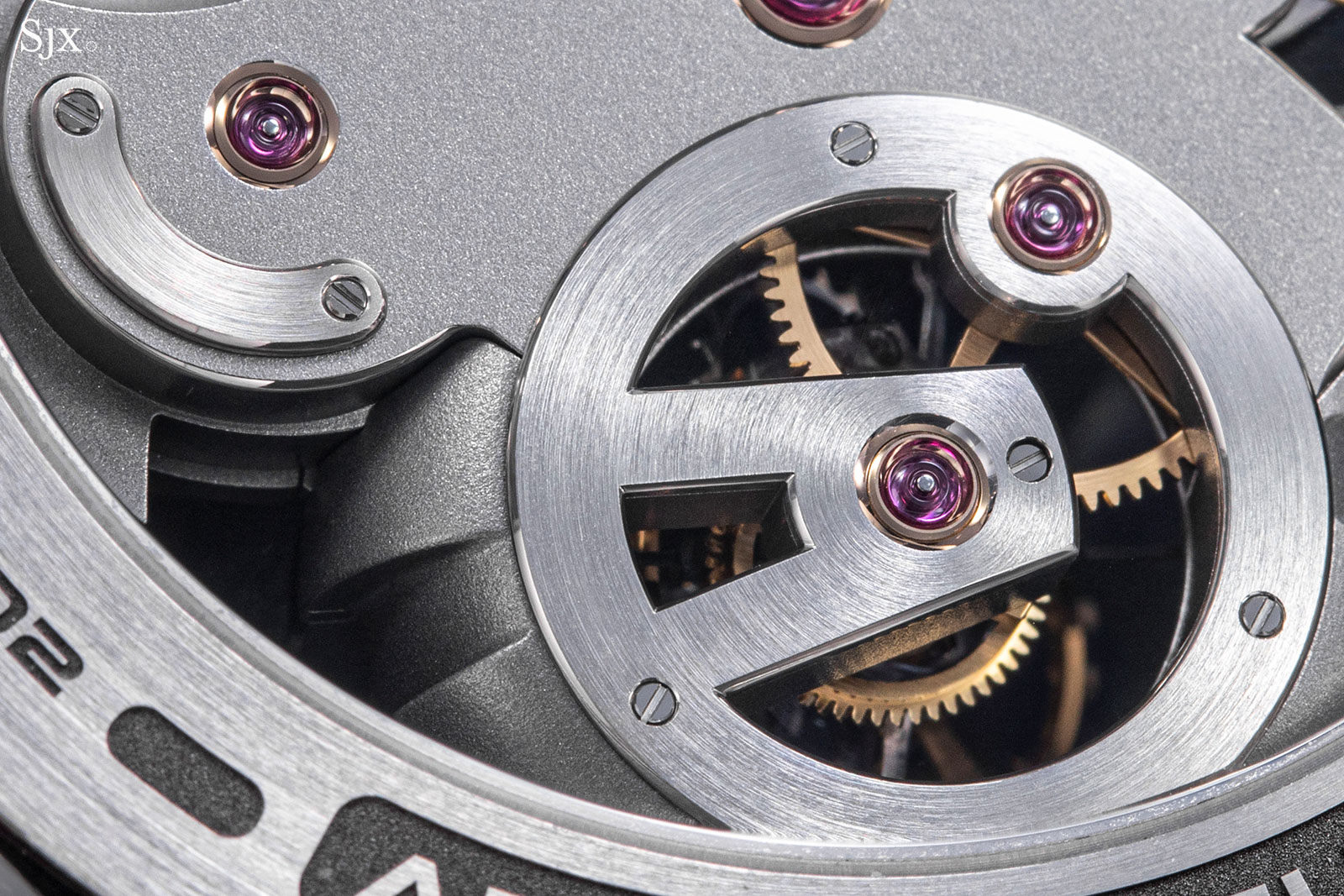

While the main plate visible through the back might seem sparse compared to the intricate front, every element is still impressively executed.

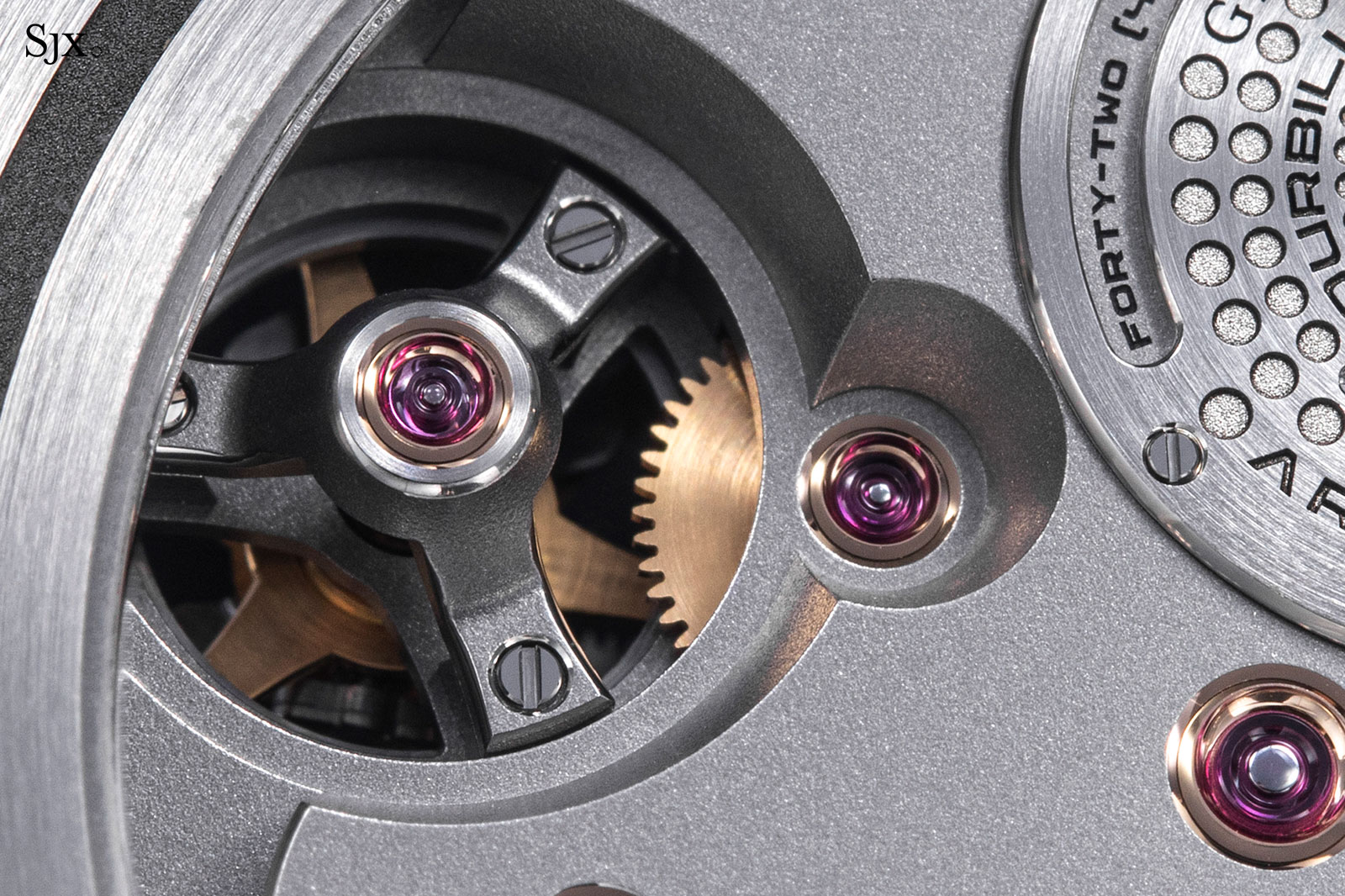

Of particular interest is the lower pivot of the differential that’s mounted on an elaborate tripod, similar to the one supporting the hands. It is equally well finished, right down to the chamfered edges and slots on the screw heads. And the tripod also sports a chaton for the jewel at its centre that holds the differential pivot. The chaton is an entirely unnecessary extra that is both beautiful and points to the mechanical function of the bridge.

But unlike the tripod for the hands, this is superfluous in regards to functionality; a simpler bridge or a closed movement plate would work exactly the same. Yet, this elaborate approach to its finish and appearance is exactly what GF movements are appreciated for. At the same time, the tripod bridge highlights the importance of the oft-overlooked differential mechanism.

One criticism would be the main plate appears too clean, as if it was a result of a purely industrial process with no handwork. Take for example the conical sloping walls around the differential tripod – they are clearly a product of CNC machining, albeit highly skilled machining as it is more challenging to machine rounded surfaces cleanly compared to just flat, vertical surfaces.

But the main plate is not merely about modern-day machining because there is much hand finishing evident. Notably, many of its edges exhibit fine, rounded anglage that’s not especially wide due to the thinness of the plate, but executed to the highest level and with an incredible uniformity.

It also helps that the main plate is finely frosted in the typical GF style, instead of sporting Cotes de Geneve. The clean appearance of the frosted surface complements the anglage well and emphasise its mirror polished nature. And for colour contrast, the gold chatons holding the rubies break the monochromatic monotony of the bridges and plate.

The complex geometry of the bridges are in fact, the main point of the Architecture – it is all about mechanical form over function, but done in a tasteful manner with impeccable and elaborate quality.

As an example of that quality, it is worth paying attention to the bridge for lower pivot of the tourbillon. While it would have been easier as a one-piece, closed plate, the Architecture opts for an approach that is elaborate, almost to the point of excess.

The bridge supporting the underside of the tourbillon cage is a massive, concentrically-brushed ring with an “A”-shaped cantilever to support the pivot. The ring also has a jewelled chaton within its edge for the pinion of the third wheel. And of course, all its edges boast uniform anglage with a generous number of inward and outward angles.

Less obvious but equally worthy of admiration is the complex, machined form of the main plate around the ring. It has an intricate, sculpted profile reminiscent of the cast-metal casings for industrial gearboxes as one might find on a large ship for instance. But of course, this is done on a radically smaller scale and intricately finishing. The surface is finely frosted and free of the machining marks that inevitably result from milling the curved profile, especially at this size.

The same can be observed on the area over the keyless works, which is a myriad of planes inclined at various angles with curved edges, offering an intriguing aesthetic that further emphasises the asymmetrical design.

In summary, the Architecture movement presents a surprising mix of elements that seem both haphazardly placed and industrial, but up close it reveals refined, impeccable finishing as expected from the brand. The result is coherent and reflective of the theme and style of the watch. In short, the design is more contemporary than GF’s earlier calibres, but the execution is just as good.

Conclusion

If it is not obvious by now, this is now a watch to be dismissed as yet another attempt at a high-end sports watch.The Architecture is a prime example of a great design executed well results in a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. Many of its constituent elements are clearly borrowed from GF’s past creations, yet the watch feels satisfyingly congruent.

While the tourbillon inside isn’t the most type made by GF, the overall execution of the movement is certainly one of the most elaborate to date. The Architecture is a watch where one should enjoy the forest instead the trees, but paradoxically the requisite level of enjoyment is only possible with the impeccably finished individual components that few others can pull off so successfully.

Key facts and price

Greubel Forsey Tourbillon 24 Secondes Architecture

Diameter: 47.05 mm (case band) and 45 mm (bezel)

Height: 16.8 mm

Material: Titanium and sapphire

Crystal: Sapphire

Water resistance: 50 m

Movement: Tourbillon 24 Secondes Architecture

Functions: Hours, minutes, seconds, power reserve indicator, and tourbillon

Frequency: 21,600 beats per hour (3 Hz)

Winding: Hand-wind

Power reserve: 90 hours

Strap: Rubber strap with titanium folding buckle

Limited edition: 11 pieces in 2022, and then 18 pieces each year from 2023 until 2025

Availability: Starting end 2022 at authorised retailers

Price: US$500,000; or 706,200 Singapore dollars including GST

For more, visit Greubelforsey.com and Sincere.com.sg

This was brought to you in partnership with Sincere Watch, the retailer for Greubel Forsey in Southeast Asia.

Back to top.