The Forgotten Most-Complicated-Watch-Ever Made for the Most Famous Banker Ever

J.P. Morgan's grand complication.

The timepieces that held the title of “most complicated watch ever”, as well as their famous owners, are mostly well known – save for the long-lost English grand complication commissioned by banker J. Pierpont Morgan.

Morgan was a great collector of watches, and his grandest timepiece was a double-dial, astronomical pocket watch made by J. Player & Son. It was the most complicated English watch ever made, and perhaps the most complicated watch in the world at the time of its completion.

Though Morgan’s watch has long been surpassed in complexity by other hands, and it bears the name of a defunct English brand, it has arguably the greatest provenance of all super-pocket watches.

Unlike James Ward Packard or Henry Graves, who were both wealthy, accomplished, and little known individuals outside their fields, Morgan is still the best known banker in history; the biggest bank in the United States today bears his name.

The grandest of all time

But first, a brisk walk through the grand complication hall of fame. The most famous most-complicated-watch-ever is, of course, the Patek Philippe Graves “supercomplication”, which sold for US$24m in 2014 and still holds the record for the most expensive watch ever sold.

Commissioned by American banker Henry Graves Jr in 1925, and delivered in 1933, the Graves pocket watch outdid the now obscure Leroy 01 that was sold in 1904 to a Portuguese millionaire. And it also surpassed the various watches produced for automobile tycoon James Ward Packard, who is often regarded as having been in a friendly rivalry with Graves, but who probably wasn’t.

More complex and unquestionably the successor to the Graves is Patek Philippe Calibre 89 that the company created for its 150th anniversary in 1989. And in 2015, title was taken by the Vacheron Constantin Ref. 57260 commissioned by an anonymous collector.

The Henry Graves Supercomplication by Patek Philippe. Image – Sotheby’s

J. Pierpont Morgan

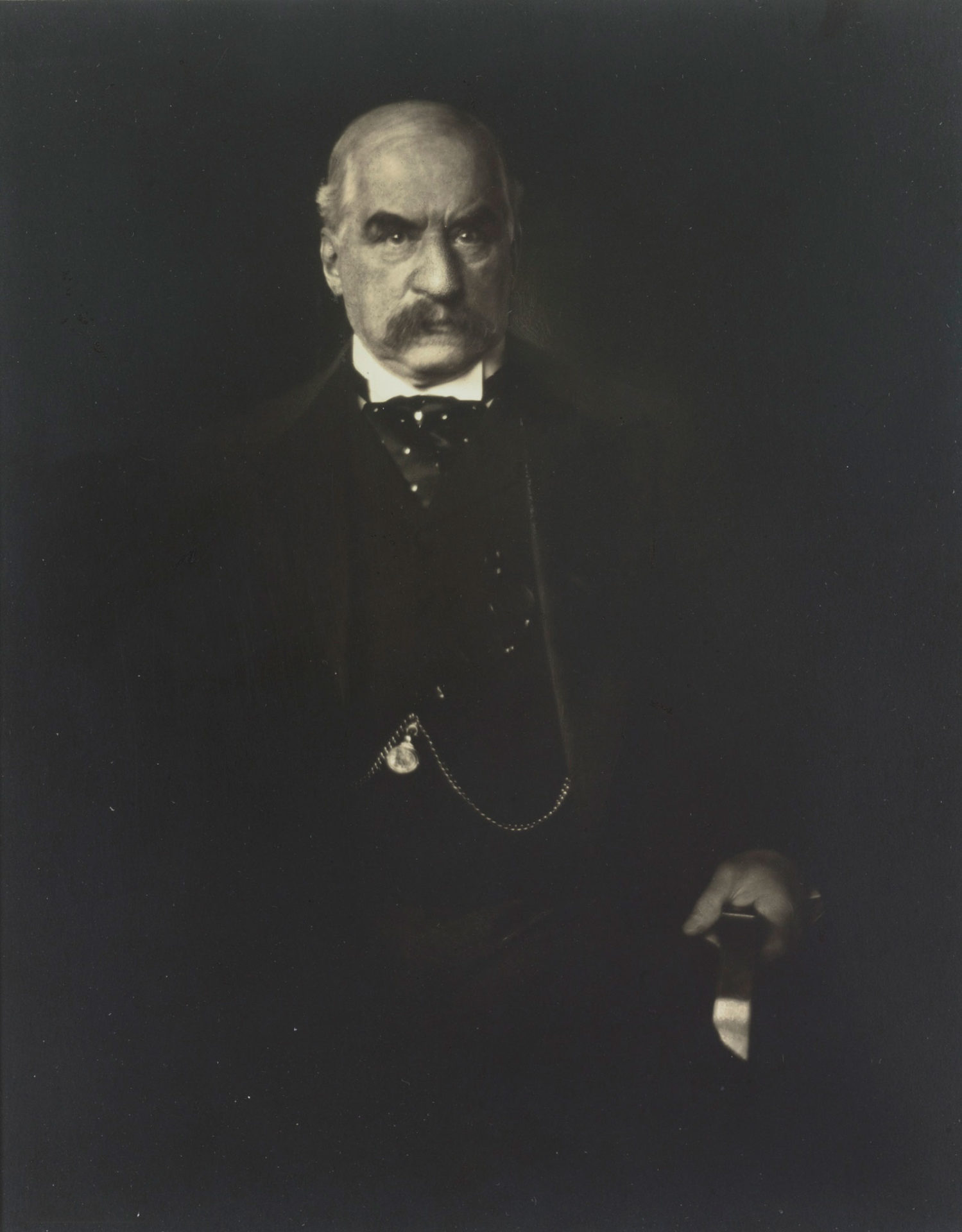

John Pierpont Morgan Sr was a prolific, perhaps indiscriminate, collector of everything – books, paintings, sculptures, clocks, watches, gemstones, and more.

In the two decades before his death, he accumulated about 20,000 objects. Morgan purchased enough precious stones from Tiffany & Co.’s chief gemologist that when the scientist discovered pink beryl, he named it morganite.

A portrait of Morgan by Edward Steichen, circa 1903. Image – Wikipedia

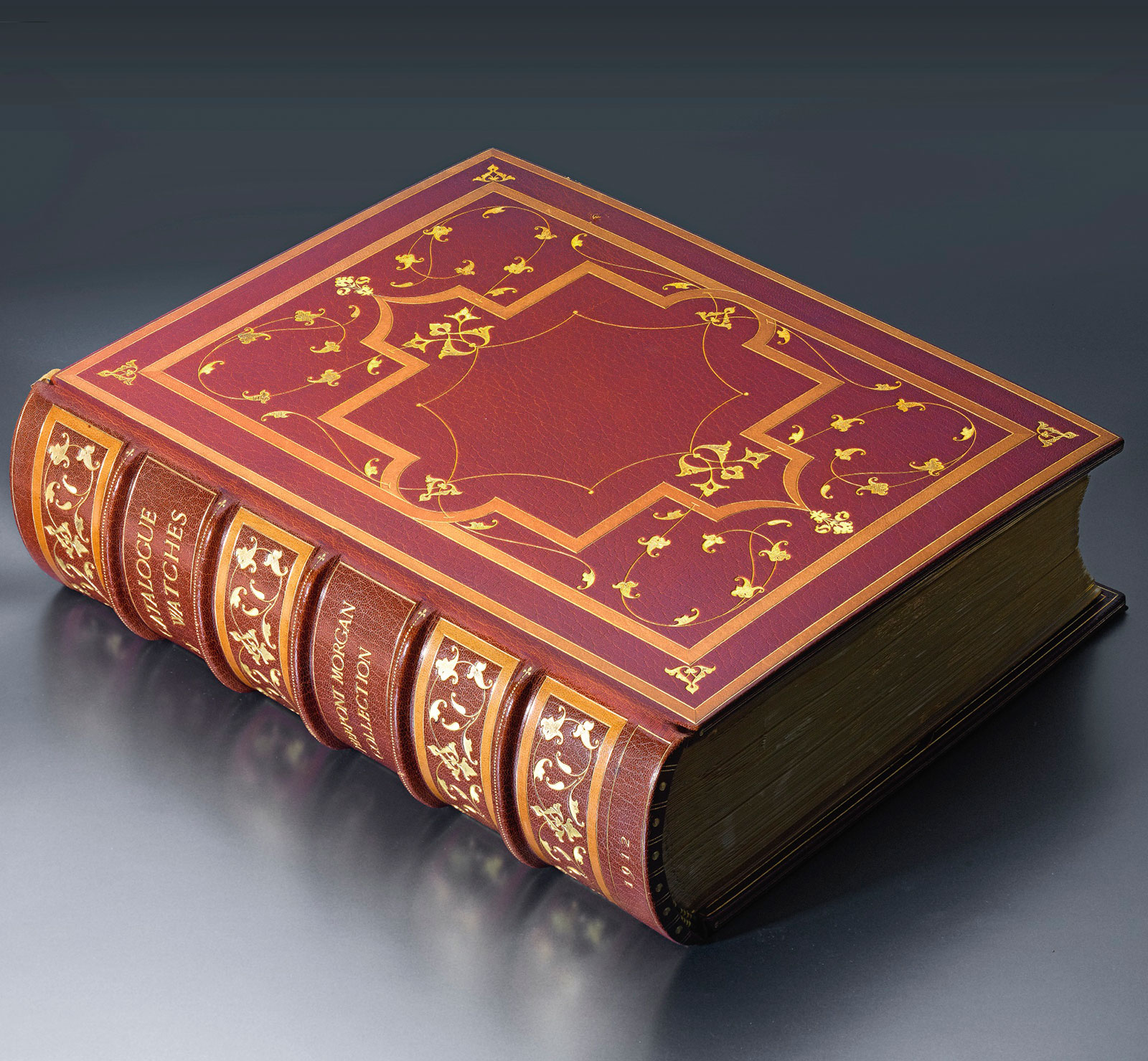

Morgan had his various collections catalogued by George C. Williamson, a noted British art historian. Some of the collections were so large the resulting catalogues were made up of several volumes; his collection of Chinese porcelain required two books, and his collection of miniatures spanned four.

The watch collection is contained within a single volume, albeit one some 350 pages long. It documents his collection of several hundred antique watches and clocks, dating from the 16th to 19th centuries and heavy on Renaissance timepieces.

A good proportion of the collection came from the acquisition of two individual collections, belonging to German watch dealer Carl Heinrich Marfels and British banker George Hilton Price. And after Morgan’s death, 250 of his watches were donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A deluxe first edition of the Morgan watch collection catalogue. Image – Sotheby’s

The most important edition of Morgan’s watch catalogue was the deluxe version of the first edition, which was published in 1912 by Chiswick Press of London.

Printed on Japanese vellum, the deluxe version of the first edition included 92 hand-painted and gilded plates depicting reproductions of the watches.

The deluxe edition, made for personal use and as gifts for friends that included royalty, was produced in extremely small numbers, most likely 15 bound in red gilt leather and 20 in black gilt leather. Reputedly, the deluxe catalogues cost so much to produce that the executors of Morgan’s estate after this death in 1913 cancelled all uncompleted books.

In the same year Morgan also printed 50 copies of the catalogue without the illuminated and gilded images, and bound them in red gilt leather.

A century later, the deluxe catalogues are probably the most expensive horological books in existence. Christie’s sold one example bound in black gilt leather for US$81,250 with fees in 2015, and more recently Sotheby’s New York sold the red version last year for US$47,500.

Reprints of the catalogue were done later in the 20th century, but as ordinary books on paper. Though rare, these can be had for several hundred dollars toady.

“An astronomical watch”

But Morgan’s contemporary watches, pocket watches he ordered during his lifetime and presumably carried in everyday life, were all made in England by the finest names of the day, reflecting the respect which English watchmaking still commanded at the time.

His family’s relationship with Charles Frodsham is well known; both Morgan and his father ordered several dozen watches from Frodsham over the decades, many of which were gifted to friends and associates, including newly minted partners at the Morgan bank.

But for his ultimate watch, Morgan turned to another English watchmaker, J. Player & Son. As it was with Packard and his final complication, Morgan’s grand complication pocket watch was ordered only a few years before he passed away, and completed in 1909.

Alongside brands like Frodsham, Edward Dent, and Samuel Smith & Sons, J. Player & Son was one of the preeminent watchmakers in the fading years of English watchmaking in the early 20th century. But it was the only one based outside of London, with its premises in Coventry, a city about two hours from the capital.

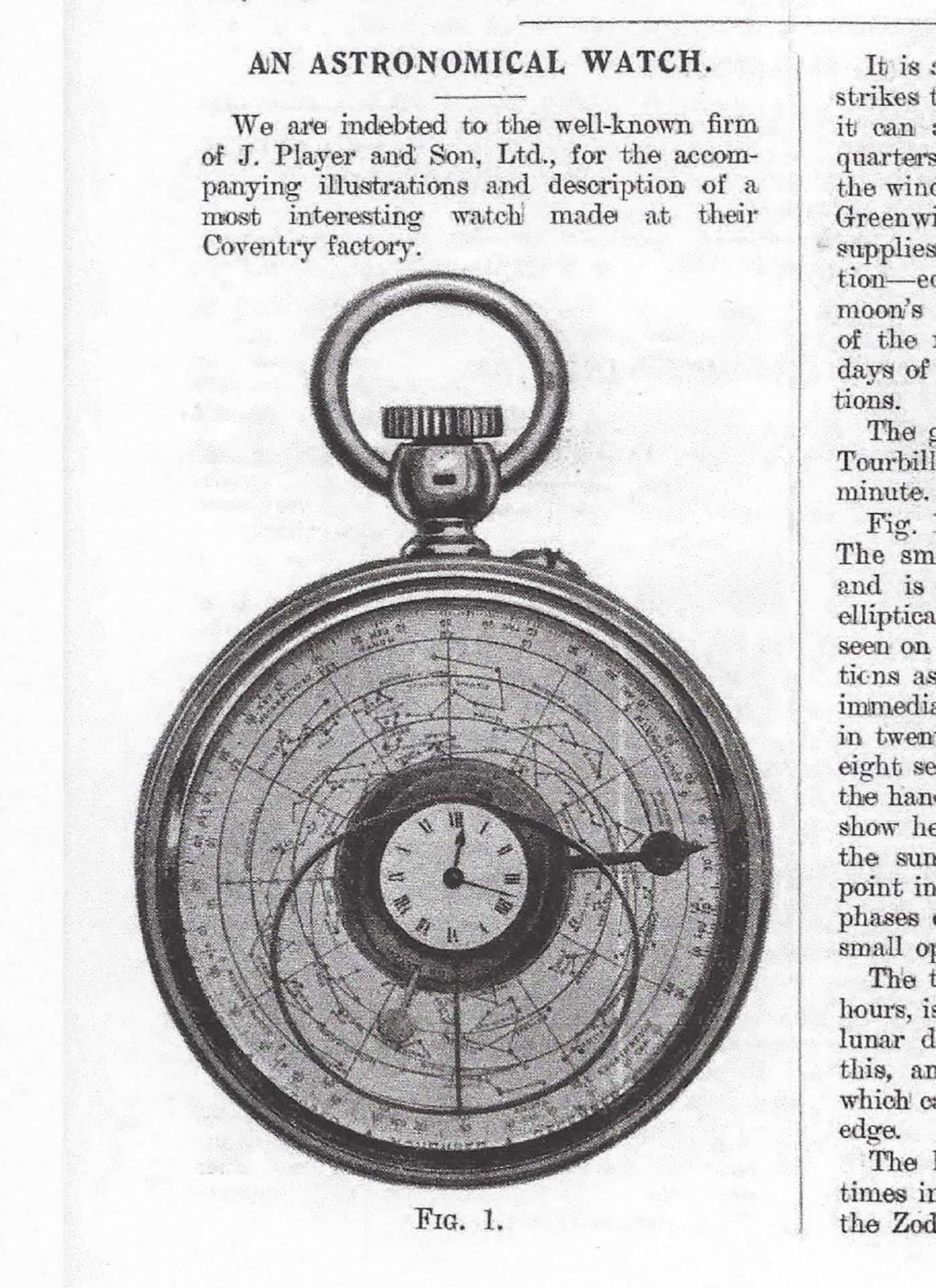

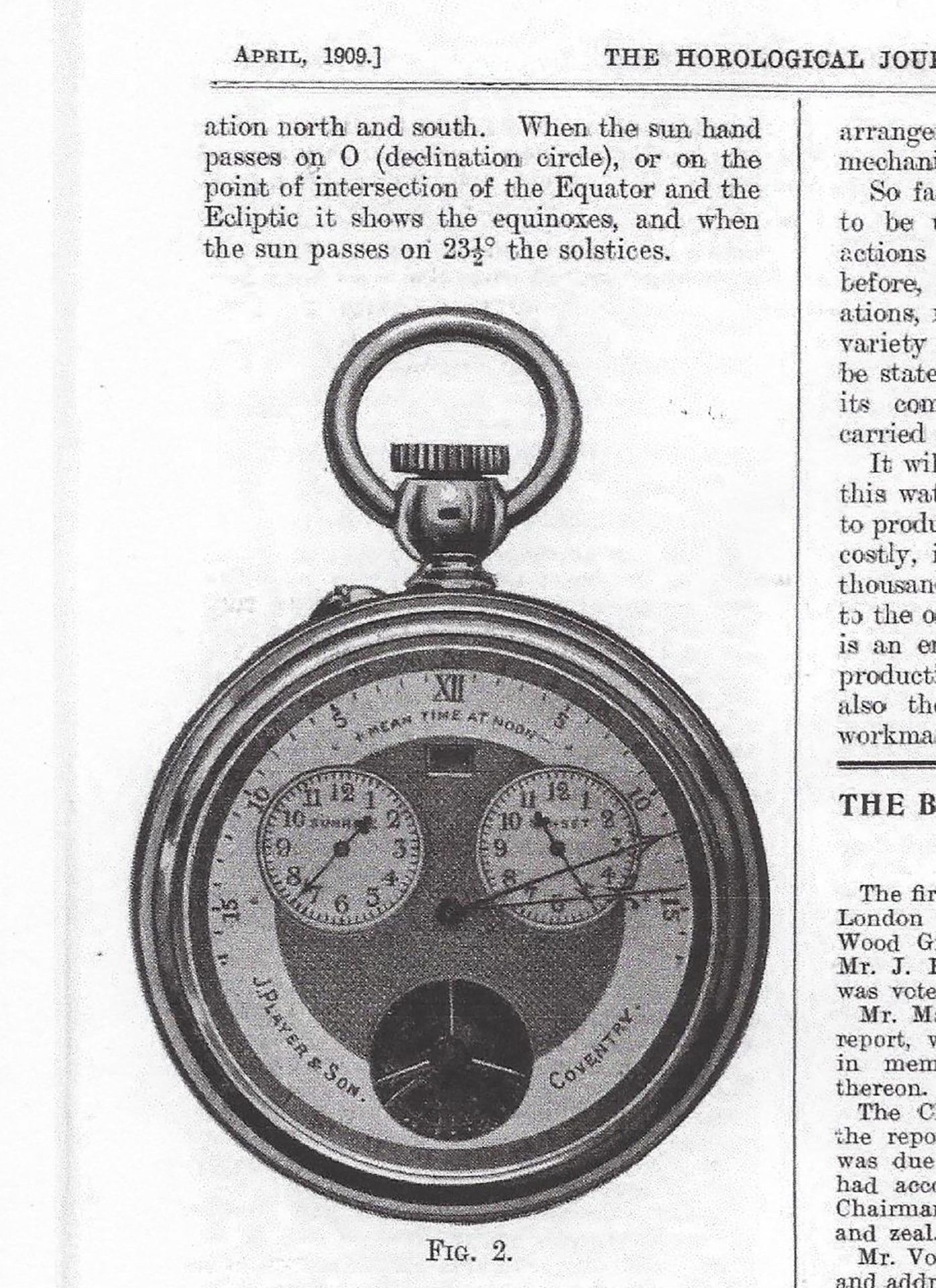

Described as a “most interesting watch” that took four years to finish, Morgan’s grand complication was covered in the March 1909 issue of The Horological Journal, the publication of the British Horological Institute, as a recently finished masterpiece.

The front of the Morgan watch as pictured in Horological Journal. Image – Antiquarian Horological Society

Although the exact details of the complications and movement are unknown, the Morgan watch is no doubt on par with the Leroy 01, or perhaps slightly more complicated.

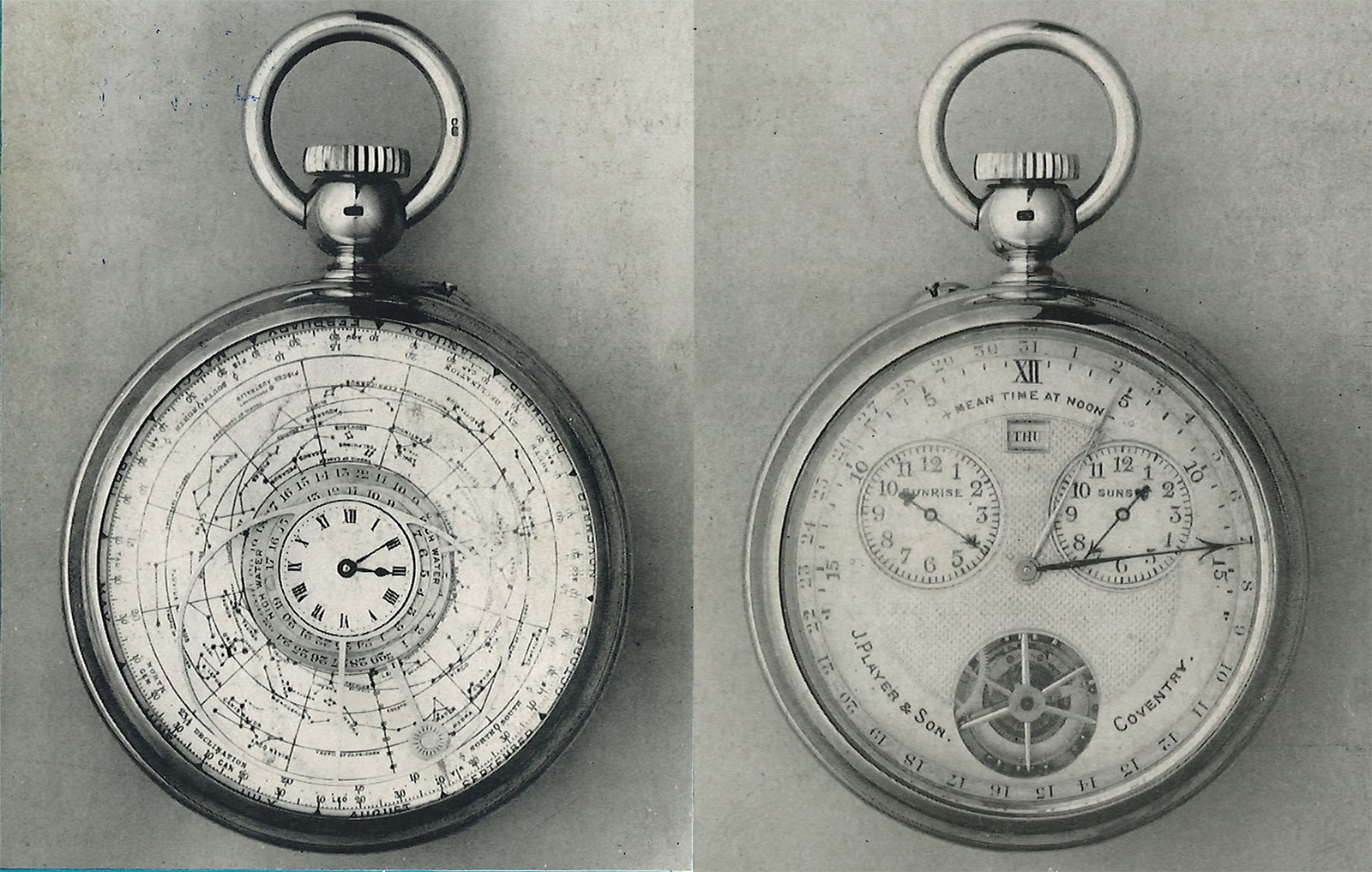

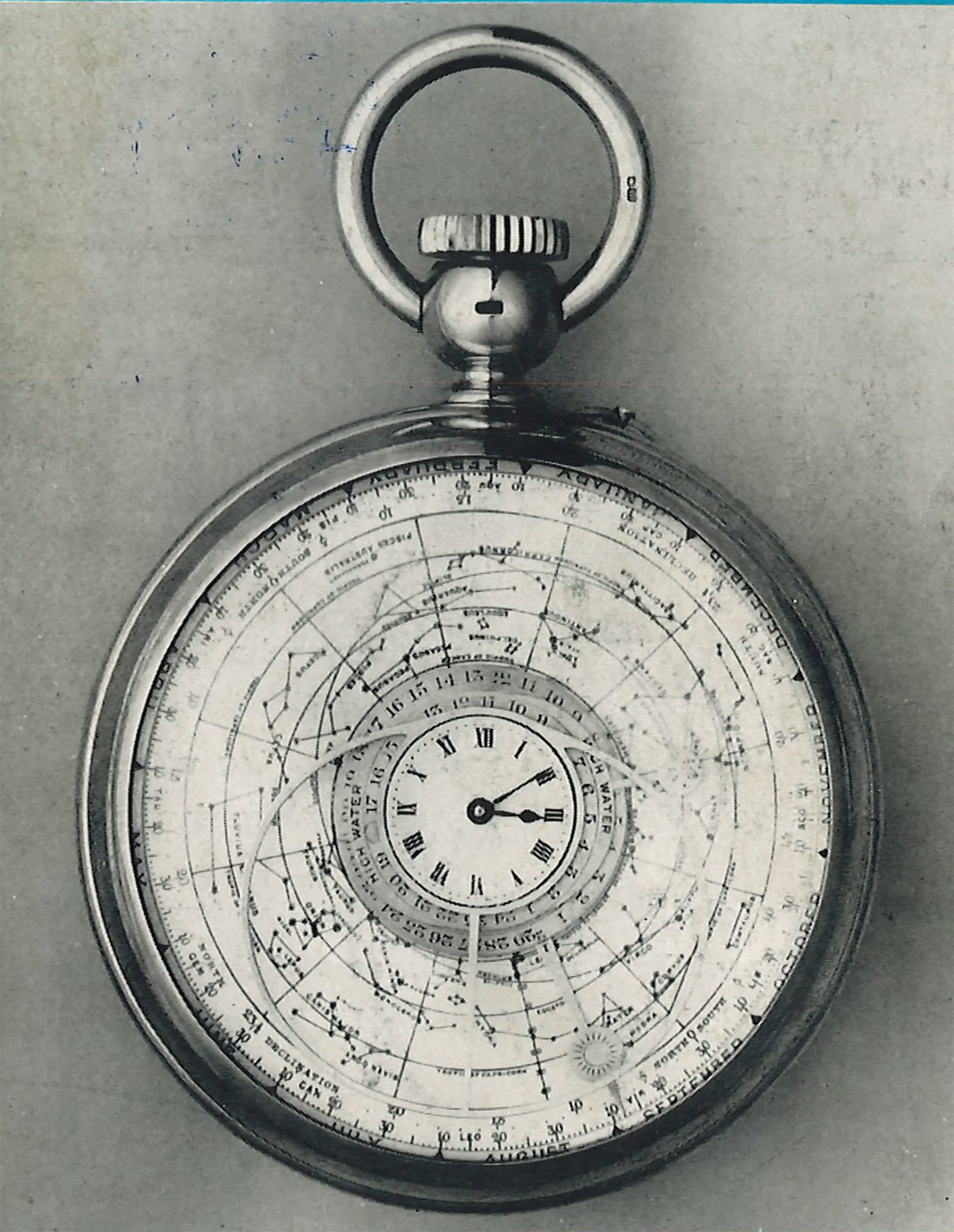

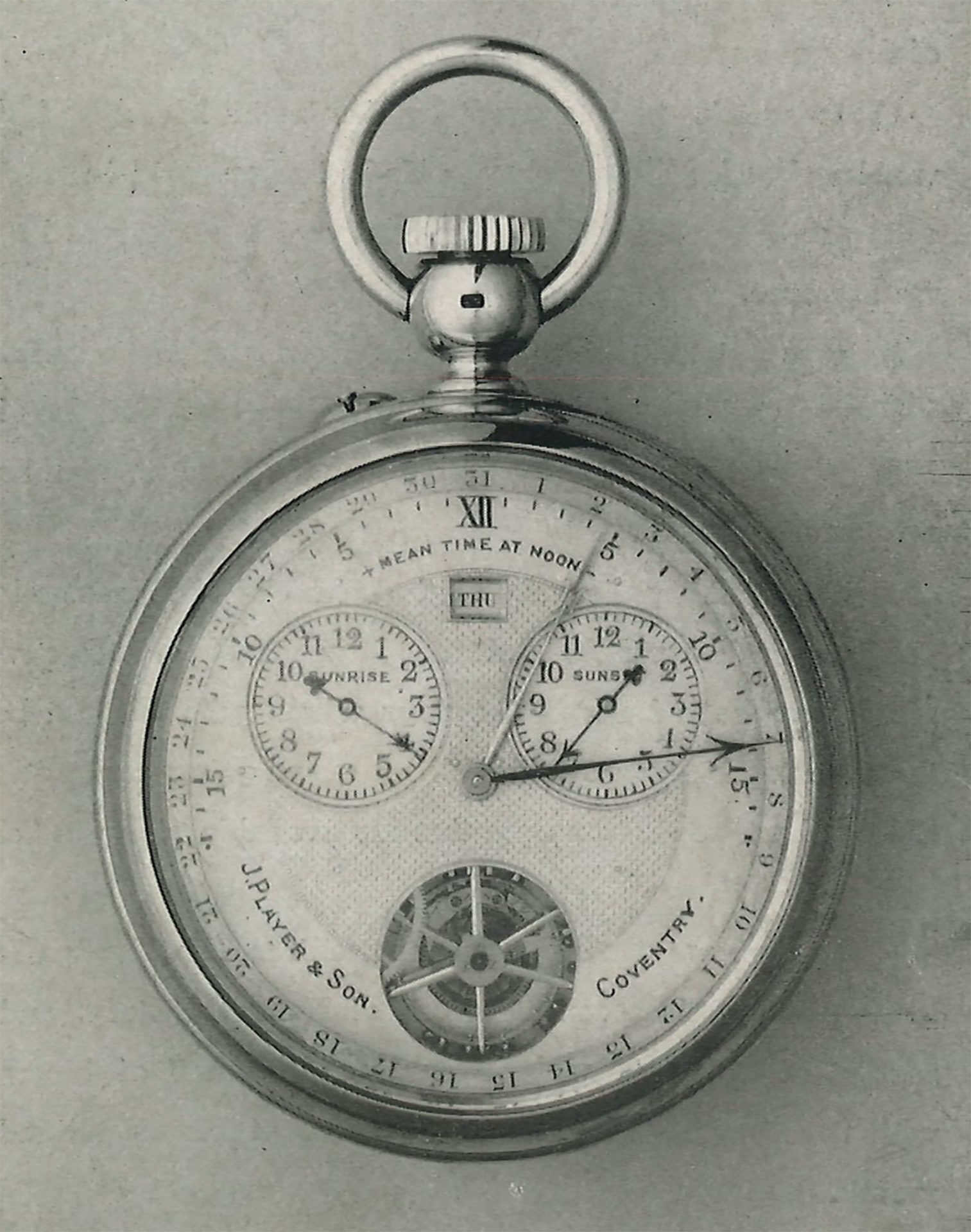

The 1909 article details the complications of the double-faced watch, which include a grande and petite sonnerie; minute repeater; annual calendar; running equation of time; times for sunrise, sunset, moonrise and moonset; moon phase; tidal level; star chart with constellations; solar declination; and a one-minute tourbillon visible through an aperture on the reverse dial.

As was usually the case with highly complicated English watches of the early 20th century, the movement was probably made by Nicole Nielsen, a London-based workshop that constructed top of the line movements, often using components and ebauches, or movement blanks, imported from Switzerland.

The reverse of the Morgan watch. Image – Antiquarian Horological Society

All of that required an 18k case that was about 77mm in diameter, creating a watch that weighed about 1 3/4lbs, or about 0.8kg.

Morgan paid about £1000 for the watch apparently, which was about double the cost of the average house in the United Kingdom at the time. But adjusted for inflation using the convenient calculator offered by the Bank of England, the cost is a surprisingly modest £110,000.

A photo of the front of the Morgan watch. Image – HIA Journal/American Watchmakers-Clockmakers Institute (AWCI)

And the reverse, with the tourbillon at six. Image – HIA Journal/American Watchmakers-Clockmakers Institute (AWCI)

Changing hands

After Morgan’s death in 1913, the watch was presumably sold. By the late 1940s, it was owned by Benjamin Mellenhoff, the then head of the watch repair department at Tiffany & Co. in New York, according to contemporary accounts in the HIA Journal, the magazine of the Horological Institute of America.

The August 1947 issue of HIA Journal. Image – American Watchmakers-Clockmakers Institute (AWCI)

The articles in the HIA Journal – the watch was featured on the cover of several issues – incorrectly describe the watch as being from the 1850s, and leave the Morgan provenance unmentioned.

The last known whereabouts of Morgan grand complication date to 1974, according to Richard Stenning, the co-owner of Charles Frodsham. It was in the possession of Jan Skala, an antique watch and jewellery dealer who had a shop on West 47th Street in New York City. Where the watch sits today is a mystery.

Many thanks to Richard Stenning of Charles Frodsham for his valuable input and research on the watch, and Davide Munari for his insight on the first edition catalogue.

Correction July 8, 2019: The deluxe first edition catalogue was printed in two versions, followed by an ordinary first edition of 50 copies.

Back to top.