In-Depth: The Digital Icons – Lange Zeitwerk, F.P. Journe Vagabondage, and Harry Winston Opus 3

Evaluating them side by side.

Digital time displays might seem like a modern invention but they have been found in watches since the early 1800s. Digital displays are found in clocks from even farther back – Lange’s trademark oversized date was inspired by the five-minute, digital clock built by Ferdinand-Adolph Lange for Dresden’s Semper opera house that opened in 1841.

But the biggest advances in mechanical digital time displays – with jumping indications – all arrived soon after the turn of the millennium. And the most important are just three – the A. Lange & Söhne Zeitwerk, F.P. Journe Vagabondage III, and Harry Winston Opus 3 – and now we’re going to put them side by side.

The five-minute clock that sits just above the stage in the Semperoper, showing 07:30 pm. Photo – A. Lange & Söhne

An new, old idea

Watches with a single digital display, namely a jumping hours, date as far back as the early 19th century. Enough of them were made that such pocket watches appear regularly at auction. But a single digital display does not a digital watch make.

The watch with a jumping, double-digital time display – and hence a true digital watch – was invented in 1883 when Austrian engineer Josef Pallweber patented a mechanism that indicated the time with discs, read through two windows, one for the hours and other, the minutes. He licensed the patent to a handful of watch brands, though it is IWC that is most closely associated with the Pallweber display.

At the same time, it is important to point out that we are discussing watches with jumping digital indications, as opposed to those with “dragging” displays that essentially replace hands with discs.

A vintage IWC Pallweber pocket watch from the late 19th century

But it was only in the era 2000s that the truly great digital watches arrived. The first to be announced was the Harry Winston Opus 3 – that took almost a decade to finish – followed by the A. Lange & Söhne Zeitwerk in 2009, and a year later, the F.P. Journe Vagabondage II. In 2017, F.P. Journe debuted the final, and most sophisticated, instalment of its digital-watch trilogy, the Vagabondage III.

When IWC celebrated its 150th in 2018, it debuted the Pallweber wristwatch and pocket watch, both limited editions powered by the same cal. 94200. Though the modern-day Pallweber retains the same dial layout as the 1883 original, the movement is entirely modern.

The modern-day IWC Pallweber wristwatch

But in typical IWC style the movement was built in a cleverly efficient manner, allowing it to be affordable as digital-display watches go. Though the Pallweber is good value – the pink gold model retails for less than half the equivalent Zeitwerk – it is not sufficiently elaborate to be part of this comparison.

Another watch worth mentioning is the impressive De Grisogono Meccanico dG that was launched in 2009. Powered by a movement developed in-house, the Meccanico dG featured a double time display – showing the hours and minutes with hands as well as digitally. It was contained in a massive oblong case that made quite a statement, but the movement’s track record in terms of reliability was mixed. De Grisogono has long gone bust, though the Meccanico dG does pop up on the secondary market from time to time for relatively reasonable money.

The Meccanico dG. Photo – Christie’s

Overview

Despite each of the three being amongst the most complicated and expensive digital-display watches ever, none manages to show all three units of time – hours, minutes, and seconds – digitally.

The Zeitwerk has digital hours and minutes, while the Vagabondage III shows the hours and seconds digitally. The Opus 3 comes closest to realising a comprehensive digital display, but its seconds indication is actually a seconds countdown to the next minute, and not a running digital seconds.

This reflects one of the fundamental challenges in a mechanical movement – storing sufficient energy in a tiny space – that remains insurmountable in terms of a comprehensive, hour-minute-second digital display.

Opus 3

Unveiled with great fanfare in 2003, the Opus 3 was the third project in the Opus series by Harry Winston Rare Timepieces (HWRT), the watch division of the New York jeweller. Conceived by Vianney Halter and designed with the help of Frenchman Pascal Pages, whose work includes the Goldpfeil jump hour, the Opus 3 was fantastical – and a fantasy with ambitions that exceeded the possibilities of watchmaking.

The series was inspired by Opus One, the joint venture between Mouton Rothschild and Robert Mondavi that created the first California “cult wine”. Like the wine, the Opus watches were an annual harvest, each created by a notable independent watchmaker together with HWRT. The concept was the brainchild of the then-chief executive of HWRT, Maximilian Büsser, who departed HWRT in 2005 to establish MB&F, a brand built on the same collaborative idea.

While the first and second Opus watches, made by F.P. Journe and Antoine Preziuso respectively, were conventional, round timepieces powered by existing movements, the Opus 3 was radical. Inset within a squarish case were six portholes for the digital time display that showed the hours, minutes, date – and most incredibly, a jumping seconds countdown.

The hours and minutes are indicated in each of the corner windows on the front, while the date numerals are in the centre pair of apertures. But in the final four seconds of every minutes, a seconds-countdown discs swings into view in the upper right window, which otherwise shows the first digit of the hour.

Now positioned over the hour disc, the countdown disc indicates the last four seconds of the minute, showing “56” to “59”, and then the twin minutes discs in both bottom-corner windows jump to show the next minute. While all this is happening the date indication in the central windows remains stationary since it only changes once a day at midnight.

The hours are indicated in the two windows in the upper corners, while the minutes are shown in the lower-corner windows, and in between them are the digits of the date arranged vertically; shown above is 02:42 on the 22nd of the month

Never before had a mechanical watch possessed an entirely digital time display, let alone one that also indicated the date and seconds countdown. But the Opus 3 as originally conceived didn’t work, which was unsurprisingly given the laws of physics and the consequent limitations of a mechanical movement. One of the primary problems was power reserve – even when the display was functioning correctly, it would run for just a handful of hours, and that on a good day.

In the years after its launch, Harry Winston recruited a variety of noted watchmakers and constructors to perfect the movement, including in 2005 Laurent Besse (who constructed the MB&F HM4 movement). Eventually Mr Halter departed the project entirely and it was handed to Renaud & Papi (APRP), the respected complications workshop that’s part of Audemars Piguet.

The Opus 3 movement as realised by Renaud & Papi

A team led by Frederic Garinaud, who later became an independent watchmaker and developed his own Opus 8 that never made it to market, achieved a reasonably functional prototype by 2009. The movement had been entirely revamped and looked nothing like the original, but the first examples were delivered in 2010. The planned 55 pieces trickled out over four years, and delivery was complete by 2014.

The last examples of the Opus 3 took a decade to go from launch to delivery, but even now anecdotal evidence suggests the movement is finicky. Of the six examples that I know of, three had to return to the factory for repairs under warranty. And the example I borrowed for this article did not work reliably. But it remains a unique and truly exotic watch.

The Opus 3 as it was launched in 2003. Photo – Harry Winston

Zeitwerk

In contrast to the drama of the Opus 3, the Zeitwerk made it to market in a typically German, well-engineered manner. Unveiled in May 2009 in Berlin, the Zeitwerk’s roots originated in a sketch from a decade before according to Lange’s head of development, Anthony “Tony” de Haas.

As Tony explained in 2018, the original idea came from the late Günter Blümlein, who in early 2001 envisioned a digital watch with Pallweber-like display as well as a moon phase. Regarded as the key figure behind the modern-day success of the trio of brands he oversaw – IWC, Jaeger-LeCoultre and Lange – Blümlein never lived to see his idea realised, having passed away in October 2001.

Development of a digital watch began in 2004, but the starting point was the dial layout: it was to have a horizontal and linear digital display in order to show the time as it is read intuitively. And after various design experiments, the dial was also endowed with its distinctive wing-shaped bridge.

After the Lange 1 and Datograph, the Zeitwerk is doubtlessly the third iconic A. Lange & Söhne wristwatch in both aesthetics and mechanics. At the same time, it is significant in a broader sense, being the first wristwatch to display the time digitally in a horizontal line.

That might not seem like much, all electronic digital watches do that after all, but in a mechanical watch it’s a substantial achievement, especially with the size of the Zeitwerk display. The straight-line display also explains why its crown is relocated from at the conventional three o’clock position.

The Zeitwerk did run into some teething problems in the year after its launch, but the issues were resolved swiftly. Since then the Zeitwerk has remained exceptionally reliable and robust, an outstanding achievement for such a complex movement – one that is far more complex than its design or price implies.

After the original was introduced in 2009, Lange has added on to the original movement to create more complex variants. They include the recent Zeitwerk Date, as well as the Decimal Strike and the flagship Minute Repeater. But while it is the simplest, the original Zeitwerk still boasts the greatest purity of concept and design.

The most advanced version of the Zeitwerk to date, the Zeitwerk Date (no pun intended)

Vagabondage III

The tale of the Vagabondage series spans some two decades, but one that was characterised by slow and steady progress towards the summit.

The beginning was in 1997, when Mr Journe completed the Carpe Diem, a one-off watch built for a Parisian collector. It was a round wristwatch with a wandering hours as well as an exposed balance wheel, powered by a custom-made automatic movement.

As the story goes, Cartier became interested in have Mr Journe further the concept, presumably for the launch of the high-end Collection Privee Cartier Paris (CPCP) that debuted in 1998. But the project fell through, leaving Mr Journe with plans for what might have been a Cartier.

Then in 2004, he was asked to do something for the 30th anniversary auction of Antiquorum – then led by Osvaldo Patrizzi and the world’s most important watch auctioneer by a large margin – so Mr Journe completed the unfinished project and created three unique examples of the first Vagabondage, one in each colour of gold. Two years later, Mr Journe debuted the serially-produced Vagabondage I, a limited edition of 69 watches that became the first of a planned trilogy.

A diamond-set version of the Vagabondage I

Not exactly a digital-display watch, the Vagabondage I was like the Carpe Diem, a wandering hours with an exposed balance wheel. But as unusual as the display was the case shape.

While F.P. Journe watches almost all share the same round case design, the Vagabondage watches are all tortue, or “tortoise”. Legend has it that the abandoned Cartier project was to have been a Tortue, explaining the unusual shape (which has since also become the Elegante).

Then in 2010, a bona fide digital watch was created in the form of the Vagabondage II, a limited edition of 69 in platinum and 68 in gold. The watch indicated the hours and minutes digitally, with the time display arranged vertically, culminating in a sweep seconds at six.

While its case retained the same tortue shape, but the Vagabondage was larger than its predecessor due to the significantly more complex movement, which required a remontoir d’egalite constant force mechanism for the digital display. Fortunately, Mr Journe had already invented a remontoir in 1999 for his original tourbillon, and repurposed the original for the jumping display.

The Vagabondage II

Finally in 2017 the trilogy was completed with its most complicated chapter, the Vagabondage III, the first and only watch with a constantly-jumping digital seconds. Driven by its own going train, the digital seconds also required a remontoir d’egalite. That was paired with a conventionally-driven digital hours and an ordinary minute hand.

Like the Zeitwerk, the Vagabondage III suffered from problems with the time display mechanism early on – anecdotal evidence suggests the problems were widespread – but they were rectified and the movement is now (mostly) problem free.

Case form and on-the-wrist

Flat and compact, the Vagabondage III is the most easily wearable. At the same time, it is surprisingly weighty for a small watch – a welcome characteristic in an costly, complicated watch – but the weight is well distributed and the watch clings well to the wrist.

On the other hand, both the Zeitwerk and Opus 3 are top heavy, so they don’t sit as well. That said, the Zeitwerk does wear better than the Opus 3, mainly because of its conventional shape and widely-spaced lugs, which give it a decent balance.

Inspired by the arch above the doorway of Harry Winston’s flagship New York store, the hinged lugs on the Opus 3 don’t help much with ergonomics especially since they are close together, which throws off the equilibrium of the watch. And the lugs also sometimes clink against the case, which can be a minor annoying.

Despite the so-so ergonomics, the Zeitwerk and Opus 3 do live up to their nature as luxury watches in tactile feel. They feel expensive; the sensation when handling either of them is one of dense solidity.

Zeitwerk

All three watches are vastly different in shape, but the Zeitwerk is clearly the biggest by volume. The size is very much in the character of Lange, which tends to build large watches that get even larger when they are complicated.

The Zeitwerk looks and feels exactly like a large, complicated watch. At 12.6 mm, it’s thick but not overly so, although it looks appear taller than it is due to the bulbous bezel that emphasises the case height. Everything is conventional and identical in style to other Lange watch cases, except for the crown. Its unorthodox one o’clock position gives the watch some novelty, but the Zeitwerk remains a stately watch.

Despite being simple in form, the case is of excellent quality, as is typical of Lange. It certainly exceeds the average round watch case put out by its peers. Most notably, the lugs are fabricated as individual pieces and then soldered into the case.

That’s a necessity of the case design and finish, which incorporates a pronounced notch between the lugs and case sides, as well as contrasting surfaces finishes on the two parts. (On other Lange models, like the Odysseus for instance, the lugs are secured by screws from inside the case middle, but the principle remains the same.)

Lange cases are made by a variety of specialist suppliers, but are all of a uniformly high grade, so the particular maker is of no consequence. I’ve seen a variety of maker’s marks on Zeitwerk cases, including “CO” for Centror (which is owned by Audemars Piguet), “FT” for Efteor, and “SUG” for Sächsische Uhrentechnologie Glashütte, which is owned by Sinn and sits just down the street from Lange.

Vagabondage III

The Vagabondage III case is the opposite of the Zeitwerk’s, a dichotomy that continues with the mechanical philosophy.

Refined and slim, the case was christened plate tortue, or “flat turtle”, by F.P. Journe. It’s very much in keeping with the brand’s house style, though that’s changed in recent years with increasingly complex and large watches like the Astronomic Souveraine.

The simplicity of the case is also very much in keeping with F.P. Journe’s house style. It’s essentially a two-part case, made up of a case middle and back, both forged (or stamped) and then finished. Though not elaborate, the case is sufficient, especially give the retail price of the Vagabondage III. And like all F.P. Journe cases, it is produced in-house at Les Boîtiers de Genève, the case maker that’s wholly owned by F.P. Journe.

Given the complexity of the movement, the slimness of the Vagabondage is an achievement in itself. The case is a bit under 8 mm high, making it a hair thinner than the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak Extra-Thin “Jumbo” for instance. As a result, the Vagabondage is elegant enough that it doesn’t doesn’t feel like a highly-complicated watch, a rare feat that only F.P. Journe has managed to consistently accomplish.

Though the Vagabondage III case isn’t large, it does have presence, both physical and visually. It is weightier than it looks, partially due to the red gold movement bridges and base plate.

And it has a largish footprint on the wrist. The diameter is only 37.6 mm, but the tortue shape gives the case a larger outline than a round watch of the same dimensions. Combined with the flat, stubby lugs, and even flatter, wide bezel, the watch looks bigger than it is, in a good way.

Notably, the Vagabondage II and III are almost identical in size, and ideally proportioned. In contrast, the Vagabondage I has the same shape but is too small.

Opus 3

The Opus 3, on the other hand, is heftier and wider than it appears. Though it’s not much wider than the Vagabondage in terms of diameter – in fact, the face looks narrower due to its proportions – the Opus 3 feels more voluminous as a result of the squarish front that is dominated by brushed metal, especially when combined with the large, articulated lugs.

At the same time, the Opus 3 is unusually thick. At 13.7 mm high, the Opus 3 is the thickest of the trio, and its case design accentuates the height. That’s a consequence of the lugs, which sit high on the case, closer to the bezel than the back. Both the lug style and positioning are the key reasons for its slightly awkward fit on the wrist.

Though a side-by-side comparison of the production Opus 3 against the original prototype was not possible, I am certain the serially-produced watch is slightly wider and thicker than the original. Going by the positions of the portholes for the time display, it is quite clear the proportions were changed, almost certainly due to the revised movement.

Despite the revisions to the design, the style of the Opus 3 case is a perfect match for the style and complication of the watch, giving it the appearance of a quirky and sometimes unreliable robot.

Amongst the trio, the Opus 3 case is by far the most complex, and likely the most expensive to manufacture. Made by Favre & Perret, the case maker that’s been owned by the Swatch Group since 1999, the case has excellent finish and construction, save for one detail. The inner section of the underside of the lugs, which has been oddly left unfinished, leaving the machining marks still visible. Unlike certain mechanical parts in a movement that are necessarily unfinished due to tolerances or thinness, I can’t think of any reason not to finish this surface.

Usability and telling the time

All three watches fall short, literally, with power reserve. The Vagabondage is rated for 30 hours, give or take two hours, and the Zeitwerk, 36 hours (though the Zeitwerk Date doubles that to 72 hours). Though the Opus 3 is supposed to run 40 hours in theory, anecdotal reports peg the power reserve at 30-something hours at best. But given the intense energy consumption of the jumping digital displays, the short power reserves are expected and forgivable.

Each of the three has to be wound daily, but even if they run down and stop, setting the time on both the Zeitwerk and Vagabondage III is easy.

The Zeitwerk does require more time to set than the Vagabondage if the current hour is far from the time on display, as it requires scrolling through each hour one by one (a task eliminated in the Zeitwerk Date that has a button to advance the hours). Setting the time on the Opus 3, however, is a feat of endurance.

Zeitwerk

For the sole purpose of indicating the time – admittedly these aren’t really timekeepers – the Zeitwerk comes in first, doing its job in the most sensible and legible manner. The watch is interesting in design and function, but doesn’t compromise on its basic purpose.

Besides the horizontal time display, legibility is helped by the exceptionally wide discs that occupy practically all of the dial-side movement. The size isn’t obvious on the watch itself, but when put side by side with the other two, it is clear the discs of the Zeitwerk are of a far larger scale.

The only shortcoming in the Zeitwerk’s functionality is a minor one: the chamfered top edge of the crown, combined with its position close to the lugs, means it is not as easy to wind as an ordinary crown, though the disparity is minimal. According to Lange, the chamfered edge was to prevent the crown from rubbing against the wrist, so the crown design is perhaps a necessary compromise.

Still, the crown remains functional, and winding it daily is a fairly easy and enjoyable experience. The Zeitwerk’s power reserve is actually longer than 36 hours – the mainspring is massive – but a stop-work mechanism visible on top of the barrel halts everything at the 36 hour mark, after which the mainspring torque might not be able to power the remontoir. And like several other Lange watches, once the movement comes to a dead stop, the seconds hand halts at the 60-second mark, a surprisingly nifty feature though it has no real utility.

Vagabondage III

Though its discs are substantially smaller than those in the Zeitwerk, the Vagabondage is reasonably legible for an exotic-display watch. But perhaps more importantly, the Vagabondage III is dynamic, ever changing, and compelling – you want to watch the seconds jump – but it also has a finicky, mercurial character.

The highlight of the watch is the seconds display, but it is also confusing. Being the element that first catches the eye, the seconds are often mistaken for the minutes, even after several days of wear.

And because the seconds are driven by an separate going train, they are independent from the minute hand. Synchronising the two when setting the time is difficult and takes some finesse, though not impossible.

The Vagabondage III seconds in action. Animation – F.P. Journe

As the seconds are so prominent, it is noticeable when the seconds digits and minute hand are far out of sync, for instance if one is at the top of the minute and the other is halfway there. The disconnect between the two can be forgiven as a charming idiosyncrasy of an unusual watch.

Another peculiar feature is the motion of the seconds disc on the left that shows the tens of seconds. It is driven forward every 10 seconds by the single-units disc on the right, via a single-toothed wheel that turns a Maltese-cross gear, which is the common setup for a periodically rotating display. The particularities of the display means adjustment during assembly is crucial. If too much play is present between the gears, the tens-of-seconds disc will jump, and then continue to move a hair’s breadth upwards again at one second past the top of the minute.

The finicky nature of the Vagabondage III continues even when it stops. While the Zeitwerk comes to a precise end when the mainspring is halted, the Vagabondage III to gradually meanders towards a wavering conclusion. In the last five or six hours of running time, the jumping seconds on the Vagabondage begins to falter, with the disc sliding rather than jumping.

Though Vagabondage III has an power reserve indicator, it is discreetly tuck away, so the lethargic disc serves as an explicit reminder that the watch needs to be wound. Its behaviour is actually an intrinsic characteristic of the constant force mechanism, which requires a minimum amount of torque to operate correctly. The deadbeat seconds hand in the F.P. Journe tourbillon that’s equipped with the same remontoir acts in a similar manner and starts to glide smoothly as the mainspring nears empty.

Opus 3

Despite its goggle-eyed appearance, the Opus 3 is unexpected legible. The layout of the display takes a while to get used to, because the date separates the digits for the time, but it quickly becomes easy to understand.

However, the discs are set so deep into the case that there’s a tunnel-like effect when viewing the time. The depth of the discs also means there’s only a narrow angle of view to read the time. Going beyond the angle of view means the discs disappear.

In terms of operation, the Opus 3 demands a lot. It’s challenging to wind and set, even more so than a perpetual calendar.

Firstly, the flat crown has to be slid upwards in order to engage the winding mechanism. But the small size of the crown makes winding tedious. At the same time, the tactile feel of the winding click is mushy and imprecise.

Setting the time and date, on the other hand, is done with three recessed pushers on the sides of the case. Though inconvenient because they require a stylus, the pushers are an improvement over the initial Opus 3 concept, which would probably have a been a disaster in terms of user interface.

The ambitious original plan was to have a crown with four vertical positions, one for winding, and the others for setting the hours, minutes, and date respectively. Even if it had been feasible, the size of the crown and its tiny range of vertical movement would have made selecting the right position a lottery rather than a choice.

Mechanics

Zeitwerk (first and second generation)

Lange movements are usually impressively engineered, which describes L043.1 in the Zeitwerk well. Beyond its digital display, the Zeitwerk also incorporates an elaborate remontoir, or constant force mechanism, which is the most complex aspect of the movement. The part count makes clear Lange’s approach to movement construction: the L043.1 is made up of 388 parts, compared to 249 for the cal. 1514 in the Vagabondage III.

The L043.1 is logical in its layout and function. A large mainspring drives a going train that powers the remontoir, which discharges once a minute and moves the single-minutes disc forward. Because the single-minutes disc shares the same axis as the tens-of-minutes disc, both driven forward simultaneously every ten minutes, or every ten releases of the remontoir. And every 60 minutes, a finger attached to the tens-of-minute wheel advances the hour disc by one step.

Even though the L043.1 was mechanically perfect, Lange still made significant refinements to the movement in 2016, demonstrating its commitment to technical quality. Prior to that, the L043.1 had a distinctive quirk in the time display. The single-minutes disc “arms” before it jumps, so at around the 55-second mark, the disc makes a tiny move downwards, accompanied by a soft, but audible click.

This arming motion just reflects how the L043.1 was designed – I see it as a native characteristic of the movement – but some criticised it as unsightly. But now that is no longer a feature after the 2016 redesign that saw 70-80% of the minutes display mechanism changed, according to Robert Hoffmann, the Zeitwerk department head.

As a result, the second-generation L043.1 arms between 25 and 30 seconds, but the arming has no effect on the minutes disc, which remains stationary and only moves when it jumps to the next minute. Practically the entire mechanism was revised to achieve that, but the key element was replacing the solo minute gear on the first generation movement with a double-layer gear.

When the single gear of the first generation is primed, the disc inevitably moves as much as the wheel does, since both are connected, explaining the slightly motion of the disc during arming.

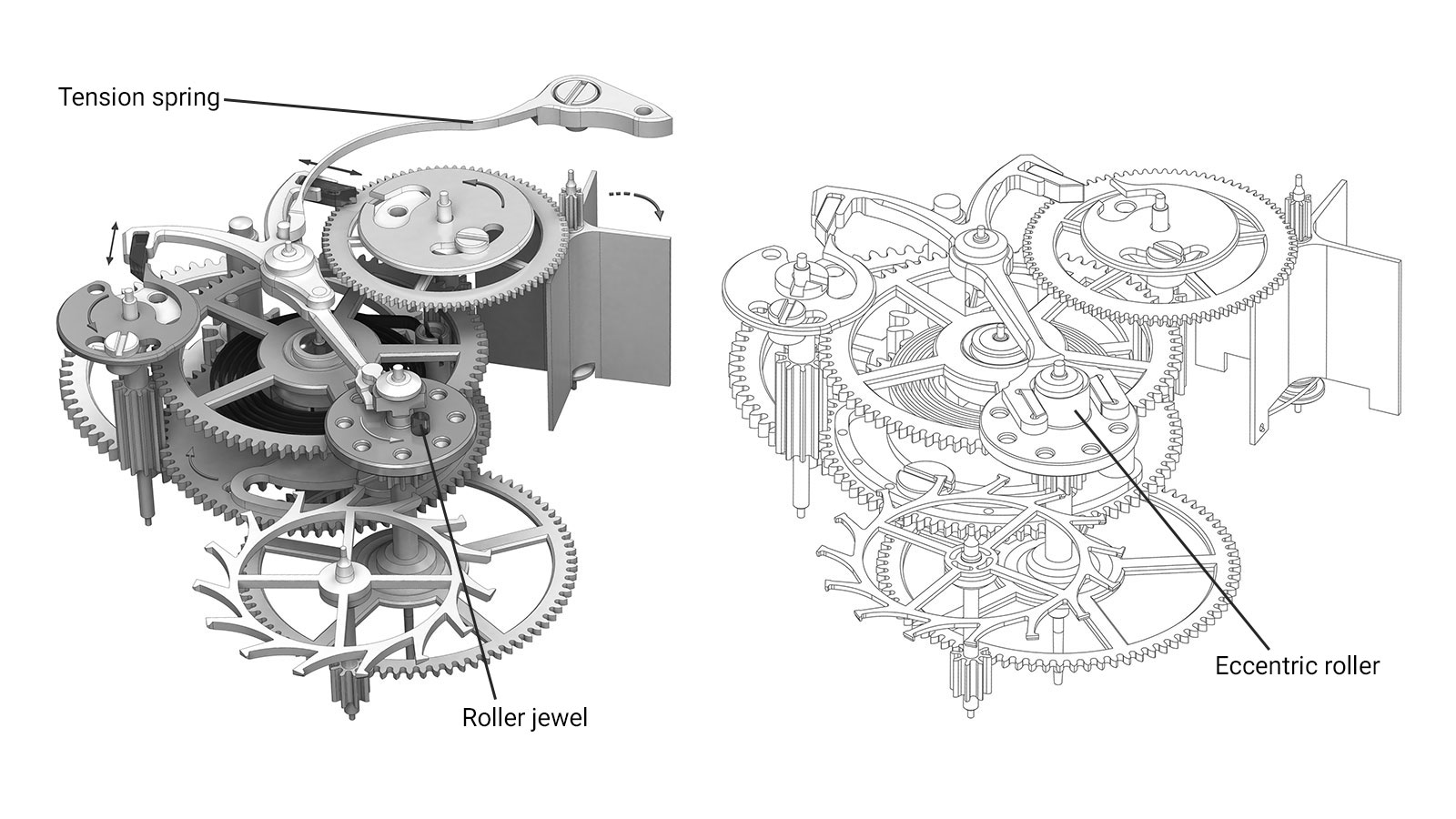

The original generation (left), and revised. Diagrams – A. Lange & Söhne

In the new generation, the minute wheel is actually two gears on the same axis, stacked one on the other. The upper gear is fixed to the minutes disc, while the lower gear has play of about five degrees on the axis, allowing it to arm and rotate five degrees, while having no effect on the upper gear.

The five-degree freedom of motion is because the lower gear is connected to the upper gear via a pin in an elongated slot, allowing the lower gear to move during the arming process as the pin travels along the slot without engaging, leaving the upper gear stationary. But as the lower gear is about to rotate for the jump, the pin reaches the end of the slot and pushes the upper gear along, simultaneously turning the minutes disc.

At the same time, the constant-force mechanism was also tweaked. Amongst other things, the constant-force mechanism has lost the tension spring for the remontoir anchor and ellipse-shaped ruby pin to release the anchor. Instead, an eccentric cylinder is mounted over the seconds wheel to effect the release.

The redesigned elements of the second-generation movement, however, cannot be retrofitted on older Zeitwerk movements as the changes as too substantial. Even the three-quarter plate on the second generation is different due to the removal of the tension spring for the remontoir, which required a smaller aperture in the plate for the remontoir.

Vagabondage III

An elegant and concise construction, the cal. 1514 inside the Vagabondage III has a primary gear train for the hour and minutes, with a secondary going train for the jumping seconds.

The primary going train is conventional and drives the the minute hand. Attached to the minute wheel is a finger that triggers the hour-jump mechanism after a full revolution of the minute wheel, or every 60 minutes.

The secondary train, on the other hand, leads off to the remontoir d’egalite. Though devised for the Vagabondage III, the remontoir operates on the same principles as the one found in F.P. Journe’s signature tourbillon wristwatch.

The constant force mechanism starts with a pivoted, rocking arm tipped with a pallet jewel at one end and tensioned by a narrow, flexible lever known as the remontoir spring.

Although the back-and-forth motion of rocking arm is slight, it transfers enough energy to the escapement to keep it going. When the rocking arm pivots far enough after a second (which is six beats of the escapement), the pallet jewel at its tip clears the star wheel. That unlocks the the star wheel, which is driven by the going train, by one tooth.

Immediately after, the going train “recharges” the rocking arm by nudging it in the opposite direction, causing its tip-jewel to lock the star wheel once again. The recharge is accomplished with a small quantity of energy that is consistent in repeat of the cycle, hence the constant force.

In the cal. 1514, the process happens once a second, with the star wheel triggering the single-seconds disc to jump as the rocking arm releases and reengages the star wheel every second.

The F.P. Journe remontoir in its tourbillon movement, which operates on a similar principle

Opus 3

Given the long and winding road taken by many individuals in completing the Opus 3 movement, most of its development history is in disparate strands. From what I understand, there’s no one at Harry Winston today who witnessed the entire saga.

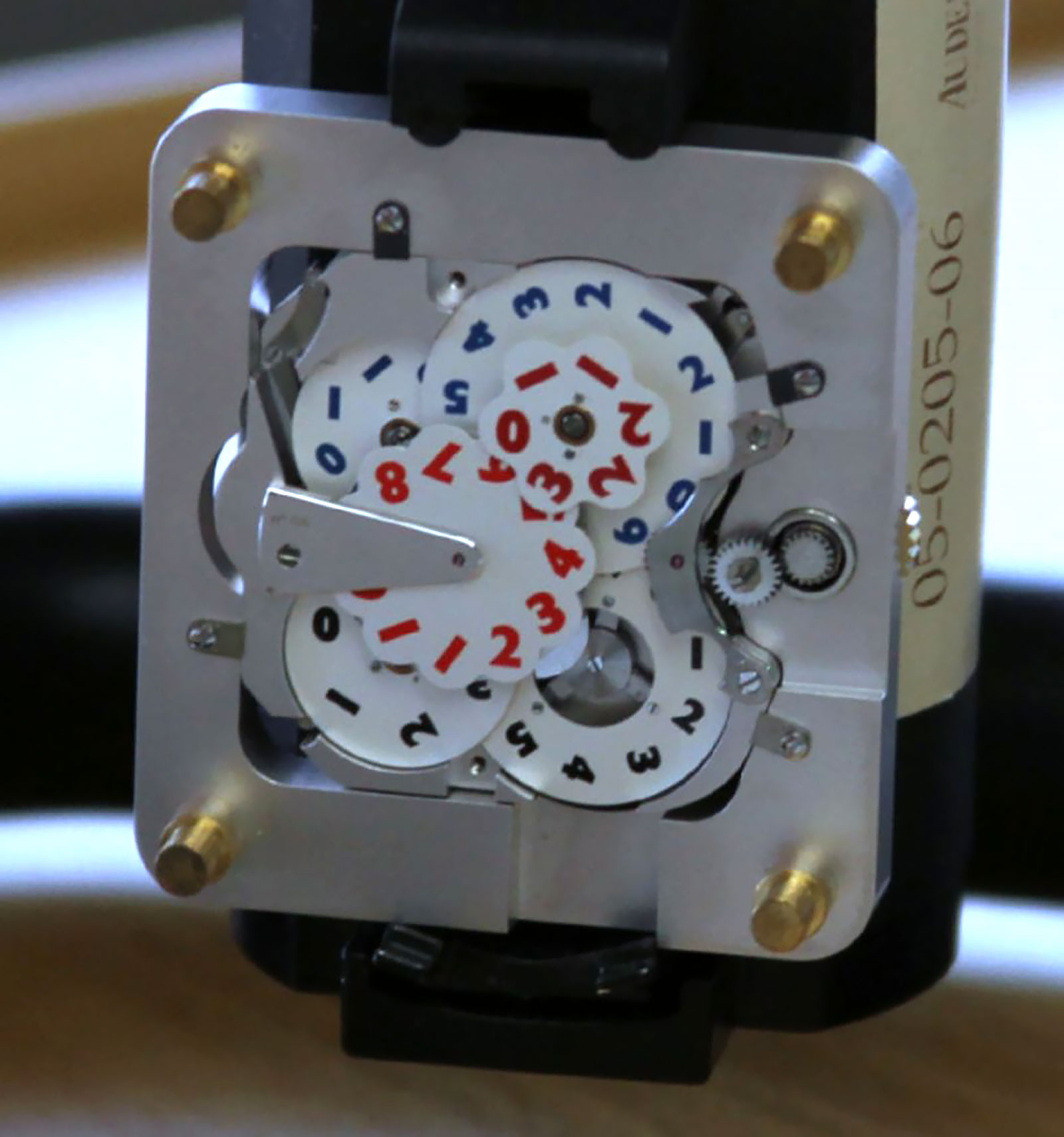

I will touch on the obvious changes to the movement. Amongst the most obvious is the reduction in the number of discs for the display from ten on the prototype to six on the final production version.

The prototype relied on double-layer discs for several of the indications, which allows for larger numerals, but brings along complexity and weight, which were presumably proved fatal to the proper operation of the movement.

The Opus 3 movement prototype when launched in 2003. Photo – Harry Winston

The Opus 3 movement completed by Renaud & Papi in 2010. Photo – aBlogtoWatch

More intriguing is the reconfiguration of the barrels, which was likely one of the primary solutions to the too-short power reserve. While the original featured two similarly-sized barrels, one for timekeeping and other to drive the display, the production movement has an extra-large barrel for the display and a smaller one for the time.

It is telling that despite the many years and changes to the movement, the Opus 3 calibre is still not quite functionally perfect. The original concept was so outlandish that it was impossible to realise with the technology and materials of the time.

Finishing

Zeitwerk

In terms of finishing, it really is no contest – the Zeitwerk wins.

As far as large, establishment brands go, Lange has no peer in terms of movement finishing. Not only is the finishing of the L043.1 well done, the movement has an intricate design that creates a lot of decorative detail to admire. There are two hand-engraved cocks, for example, one for the balance and the other for the escape wheel. And then there is the constant-force mechanism under the black-polished, anchor-shaped bridge.

While the finishing is beautiful and the architecture complex, it isn’t exactly pretty. The look is definitely more technical than poetic, with some elements that don’t necessarily sit well together.

The key visual feature of the L043.1 is the anchor-shaped bridge for the constant force that is finished to a remarkably high degree, but oddly shaped with kinks at both ends that leave it looking slightly messy. Fortunately, the latest iteration of the Zeitwerk movement, the L043.8 in the Zeitwerk date, has a tidily symmetrical bridge.

Vagabondage III

Between the Vagabondage III and Opus 3 the winner is less clear. The Vagabondage III is decorated more extensively, but the finishing is obviously uneven across the movement. In contrast, the Opus 3 has a minimal, workmanlike finish that is clearly executed throughout.

First, the cal. 1514 in the Vagabondage III has straightforward and balanced layout, with all the important bits – like the barrel and remontoir – being highly visible. As with all F.P. Journe movements, the bridges and base plate are made of 18k red gold, creating a pleasing, rich landscape that contrasts with the steel parts of the movement.

At a moderate distance the movement is attractive in both styling and finish, but up close it reveals inconsistencies as well as strengths. Historically F.P. Journe movements have never been a bastion of haute de gamme finishing, so that’s not expected, but the movement is still attractive.

The steel parts, both on the front and back, are all well finished. That is also true for the screw heads, which have chamfered slots and edges. And less obvious but worth pointing out is the perlage. It is made up of circles that are tightly but evenly spaced, and the grain (or the size of the circles) varies according to the space it covers.

A characteristic of Journe movements is a lack of sharp definition on the finishing of the bridges, be it on the bevelled edges, countersinks, or the striped surfaces, probably due to the nature of 18k gold.

And the bridges also reveal several stray marks, probably from careless handling. Such inconsistencies are mostly acceptable from a small, independent brands making exotic watches. That said, F.P. Journe is coming close to being mainstream enough that they will no longer be acceptable.

Opus 3

The aesthetics of the Opus 3 movement stand in stark contrast to its front. While the dial is quirky and colourful, the movement is plain and monochrome, with the only colour provided by the balance wheel. The finishing is essentially a drastically simplified version of the finishing Renaud & Papi does for highly-complicated Audemars Piguet movements, which means clean and sharp, but not fancy.

In contrast, the very first prototype movement showed a degree of decorative finishing. It feels as if so much effort and money was spent on getting the Opus 3 to work properly that there was nothing left to dress it up.

The base plate has an even, blasted finish, while the bridges are uniformly straight grained. Most of the bevelling is done by machine, going by the neat edges and telltale tool marks, though some of the bevels are given a final polish by hand.

And the finishing is also thorough, with the less obvious bits also taken care of. The wheels, for instance, have circular graining on their faces and mechanically-bevelled spokes. Even the escape wheel bridge, which is under the balance wheel and mostly hidden by the case back, has straight graining on its top and flanks, along with a polished, bevelled edge.

Values

Price comparisons between the three are not entirely fair, given the different numbers made and the time elapsed since their respective launches.

At the time of its launch in 2003, the Opus 3 was priced at about 80,000 Swiss francs, about double the retail price of the Lange Datograph at the time. By the time the first examples reached clients in 2010, the price had not changed by much – Harry Winston admirably stuck to the original deal and no doubt lost money on every watch sold – which made the Opus 3 a bargain when it was delivered.

The last time the Opus 3 sold publicly at auction was in June 2020, when a platinum example sold for 168,750 francs including fees, or about US$188,000, a value that reflects both the rarity of the watch, as well as the broader interest in independent watchmaking.

That interest in independent watchmaking has been turbocharged for F.P. Journe specifically. The Vagabondage III retailed for 56,000 francs in platinum and only a bit less in gold, and now sell for about four times the retail price.

The regular-production Zeitwerk in either white or pink gold now retails for US$89,200, and pre-owned specimens go for about two-thirds of that. On the other hand, the most sought-after Zeitwerk limited editions, the Luminous “Phantom” and Handwerkskunst, still sell for substantially more than their original retail prices.

Concluding thoughts

The values of the Opus 3 and Vagabondage III indicate both are desirable, for a variety of reasons. Conceived by prominent watchmakers, they are also rare, which together is enough to make them exceptionally collectable, regardless of their intrinsic shortcomings.

And both do have shortcomings. Unquestionably the coolest watch of the trio, just because it’s so offbeat, the Opus 3 lacks purity in terms of its birth. Though conceived by Vianney Halter, it was realised by a varied cast of watchmakers – each clearly talented – but so many were involved that some of the original clarity was lost along the way. And then there’s the fact that it remains an erratic performer in terms of function.

The Vagabondage III is more reliable mechanically, and manages to be wonderfully elegant in form. It’s not as quirky as the Opus 3, but unconventional enough to be strikingly interesting, even by the norms of independent watchmaking. At the same time, its concise movement construction exemplifies Francois-Paul Journe’s inventive and clever approach to watchmaking.

Of the three, it is the Zeitwerk that is technically perfect. It is more complicated than it seems, perhaps even overcomplicated, which adds to the appeal. Surprisingly, the Zeitwerk is also the most affordable in its standard versions.

But the Zeitwerk is diminished by the fact that it’s a widely-available watch, which means it doesn’t have the desirability of something that’s not available. That does it an injustice, because the Zeitwerk is an impressive watch.

Key facts and price

A. Lange & Söhne Zeitwerk

Diameter: 41.9 mm

Height: 12.6 mm

Material: Platinum, as well as 18k rose or white gold

Water resistance: 30 m

Movement: L043.1

Components: 388

Functions: Digital hours and minutes, analogue seconds, and power reserve indicator

Frequency: 18,000 beats per hour (2.5 Hz)

Winding: Hand-wound

Power reserve: 36 hours

Strap: Alligator

Availability: Versions in 18k white or rose gold are current production

Price: US$89,200

F.P. Journe Vagabondage III

Diameter: 45.2 mm by 37.6 mm

Height: 7.84 mm

Material: Platinum or 18k red gold

Water resistance: 30 m

Movement: Cal. 1514

Components: 249

Functions: Digital hours and seconds, analogue minutes, and power reserve indicator

Frequency: 21,600 beats per hour (3 Hz)

Winding: Hand-wound

Power reserve: 30 hours

Strap: Alligator

Availability: Sold-out limited edition of 69 in platinum and 68 in red gold

Harry Winston Opus 3

Diameter: 36 mm by 52.5 mm

Height: 13.7 mm

Material: 18k pink gold or platinum

Water resistance: 30 m

Movement: Opus 3 movement

Components: More than 250

Functions: Digital hours, minutes, date, and digital countdown seconds

Frequency: 21,600 beats per hour (3 Hz)

Winding: Hand-wound

Power reserve: 40 hours

Strap: Alligator

Availability: Sold-out limited edition of 25 in platinum, 25 in pink gold, and five in platinum set with diamonds

Correction June 9, 2021: The seconds countdown on the Opus 3 is a four-second countdown, and not three second as stated in an earlier version of the article.

Back to top.