In-Depth: Montblanc Manufactures Le Locle and Villeret

Production big and small, volume and artisanal.

Over the past two decades, Montblanc has evolved from a pure-play luxury pen maker into a serious contender in watchmaking. The company’s venture into watches began quite modestly in 1997, when it rolled out a line of watches powered by outsourced movements.

But it was the 2007 integration of Minerva, a fabled maker of chronographs and stopwatches, that gave Montblanc bona fide watchmaking prowess. And by virtue of its own heritage, Minerva also bestowed a degree of legitimacy on Montblanc, along with an extensive archive of historical designs ready to be mined.

Watchmaking prowess

Le Locle, and then Villeret

Earlier in the year I got to explore all facets of Montblanc’s watchmaking with a visit to Montblanc’s twin watchmaking facilities in Le Locle and Villeret. Both sit in the Vallee de Joux, the historical heart of Swiss watchmaking, and are about a 45-minute drive from each other.

Each factory is dedicated to a distinct class of watchmaking – simpler and entry-level watches at Le Locle, and haute horlogerie at Villeret. Together, the two factories give Montblanc a unique diversity that has translated into three price categories of watches.

Le Locle is responsible for both the first category, entry-level watches powered by Sellita-based movements, and the second, those equipped with mass-produced, in-house movements. Unsurprisingly, the facility produces tens of thousands of watches annually, all manufactured and assembled on an industrial scale.

Approaching the Le Locle factory in late January

The top of the line watches – mostly old school chronographs – are produced at the Villeret workshop. Just 200 to 300 watches – all hand-finished and assembled – leave the traditional manufacture each year.

Under Montblanc’s ownership, the former Minerva factory remains a niche operation that relies on an expertise in movement development and production honed over one and a half centuries.

Vision and production

Montblanc’s Le Locle manufacture is a two-building complex, each an easy five-minute walk from the other, even in the depth of winter.

The first building is largely for administration and management, housing the design and prototyping facilities as well as the office of Davide Cerrato, chief of the Montblanc watch division.

Looking more appropriately poetic, the second building is a 1906 Art Nouveau villa where the actual watchmaking happens. But both are surprisingly intimate in scale, considering the size of production.

The 1906 building in Le Locle

The final stages of production, namely assembly and testing, are done at Le Locle, which relies on movements and parts from suppliers. That includes complete movements from Sellita as well as the proprietary movements produced by ValFleurier, a secretive factory that produces movements for various watch brands of Richemont, Montblanc’s parent company.

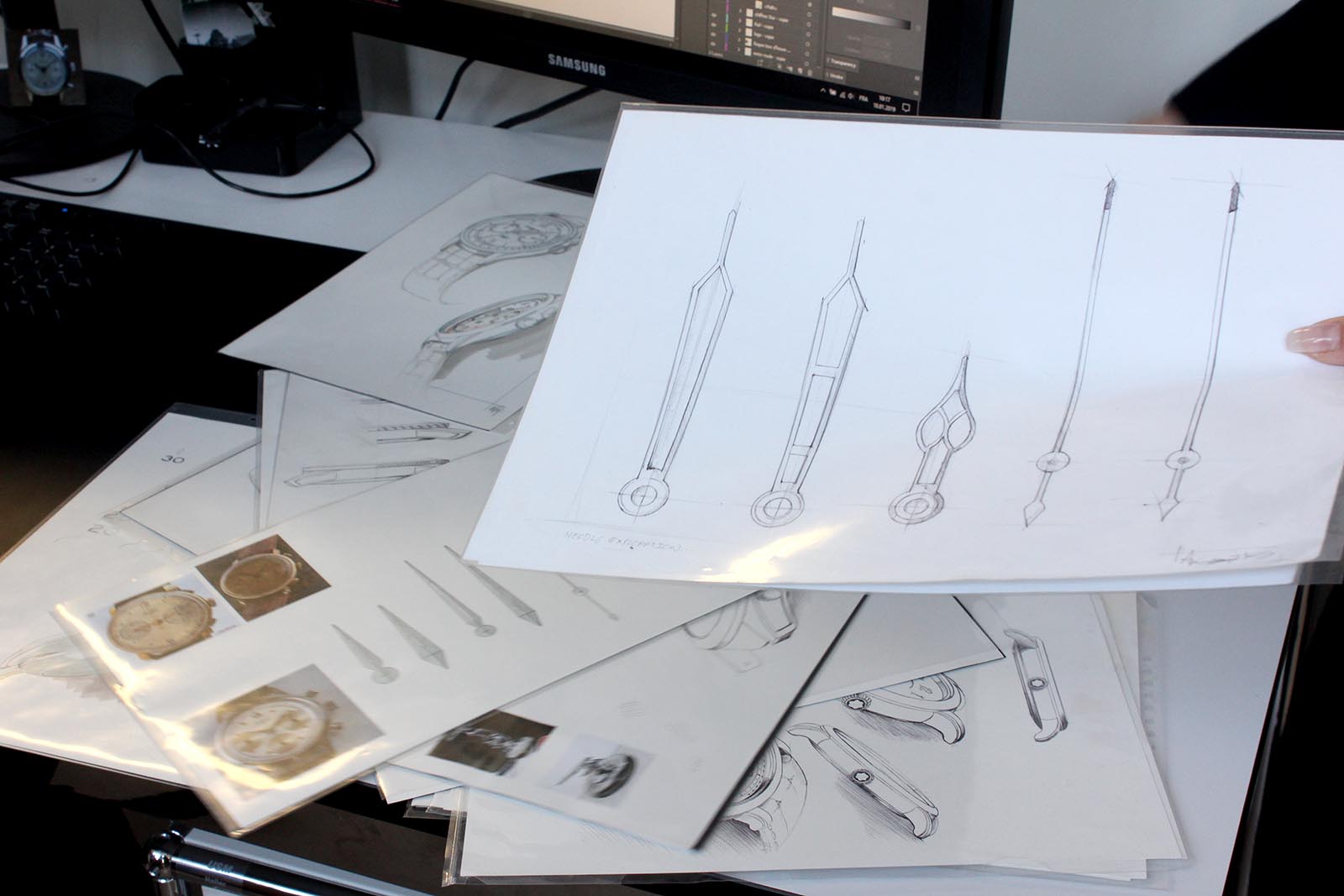

Design, on the other hand, is entirely in-house; hands, indices, dials and cases are styled in the first building by a team made up of designers and engineers who work closely with Davide Cerrato, a sharply dressed Italian whose aesthetic vision has come to define Montblanc watches.

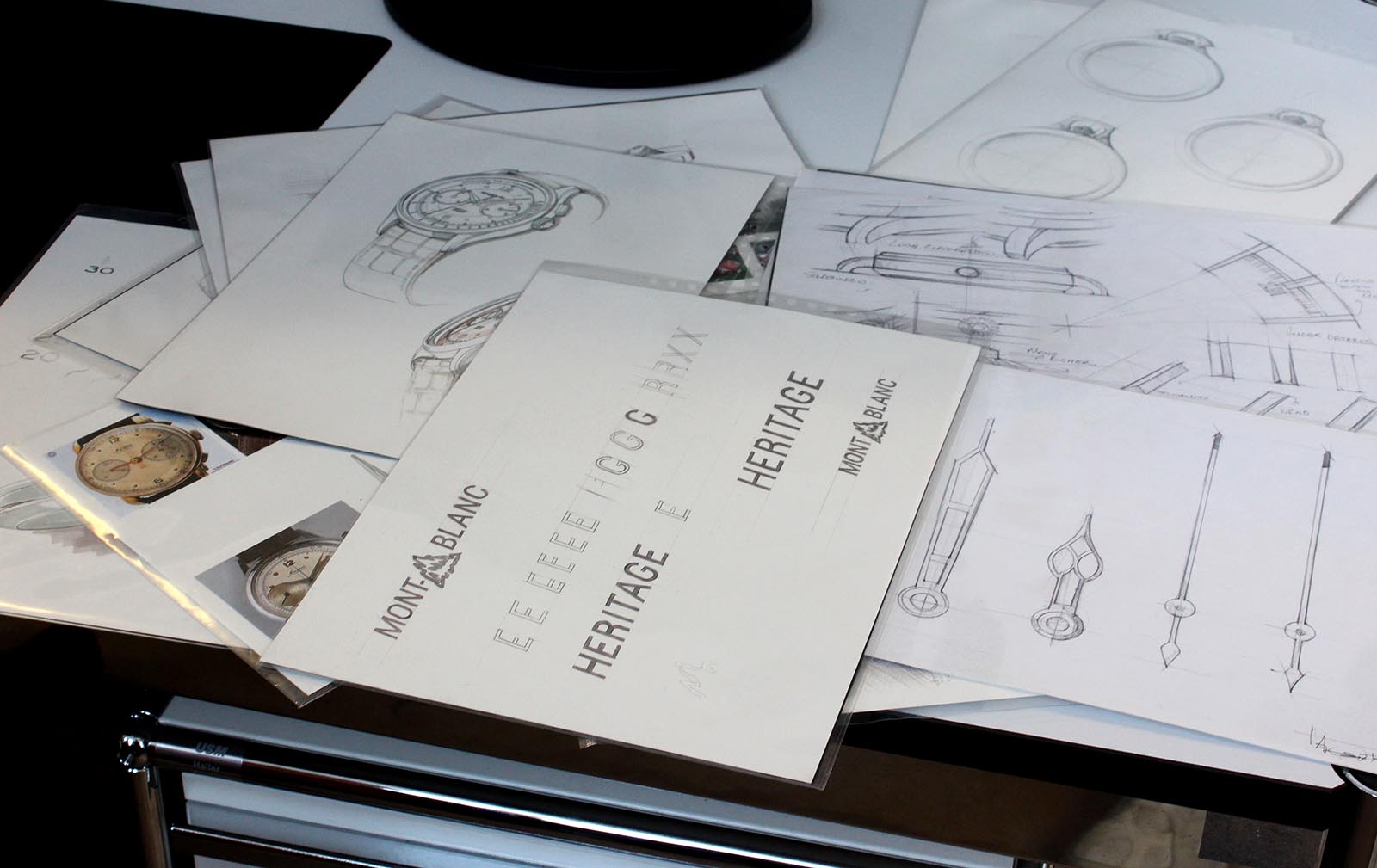

Because Mr Cerrato’s remit when he signed on was to strengthen the brand’s identity, the design work goes beyond just watches, but into small but crucial details like fonts and logos. The retro-style logo for the 1858 line of watches, for instance, was modelled on a historical emblem found on Montblanc pens.

Sketches for the 1858 collection, including the retro logo and typeface

The process of creating a new watch is pretty conventional. Watches start as drawings done by designers, which are then realised by engineers and constructors. Then prototypes are 3D printed in wax – even certain watch straps are prototyped – to create a tangible execution of the concept.

Prototype dials of the Heritage collection launched at SIHH 2019

The second building in Le Locle is where the assembly and quality control take place, including a room dedicated to the “500 hours test” of complete watches – a finishing touch to the production process that Montblanc is particularly proud of.

Here the work starts with installing the dials and hands onto movements that have been delivered complete from suppliers. A manual press is used to fix the hands in place, with varying pressure for each type of hand. After each sub-assembly is checked by the same watchmaking for functionality and alignment of hands, it’s installed into a watch case by another watchmaker along the assembly line. The process continues down the line, until the complete watch is ready for the 500 hours of testing.

Installing the hands on the “panda” dial of a Timewalker Manufacture Chronograph using a manual press

Inspecting the course of hands

The 500 hour test

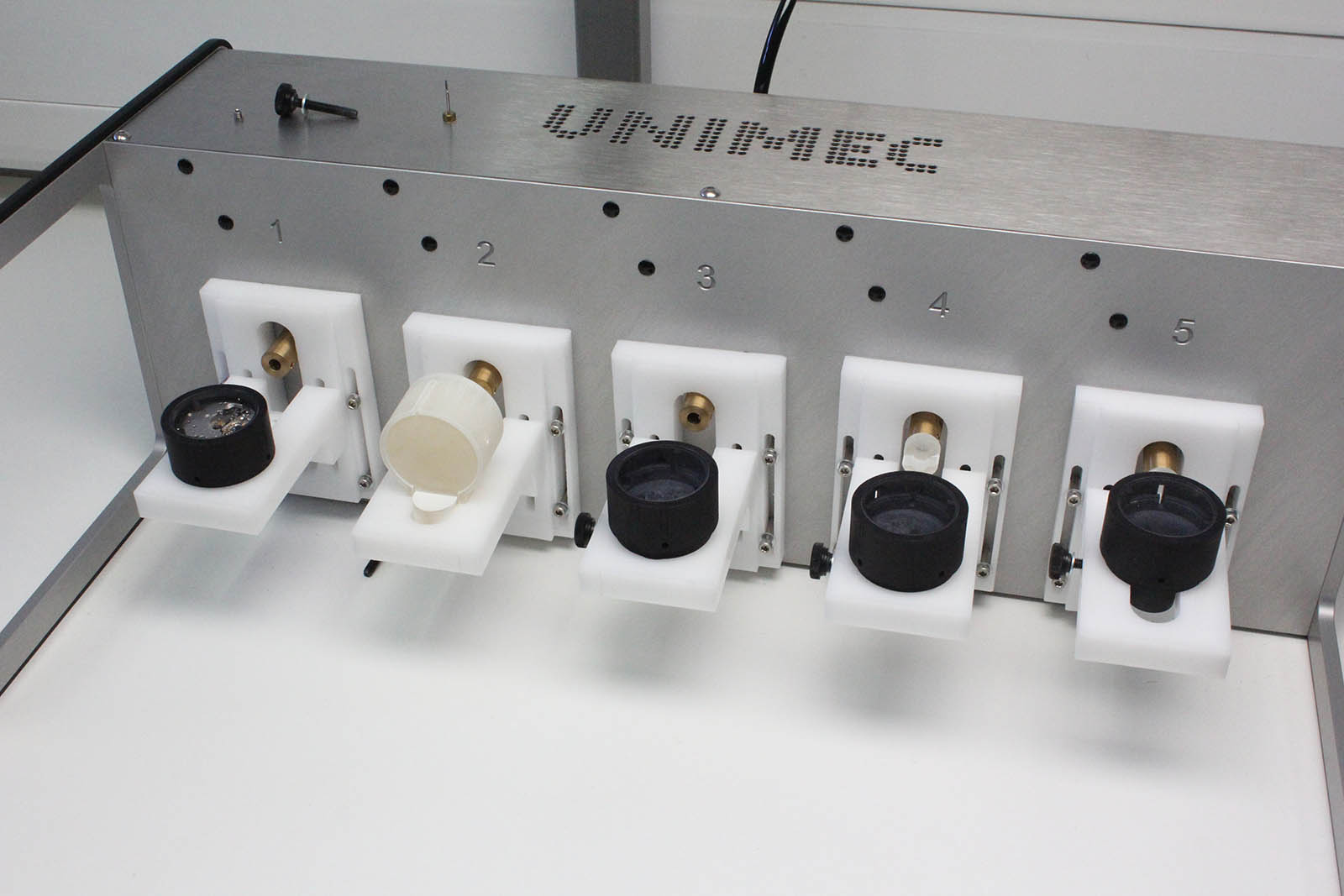

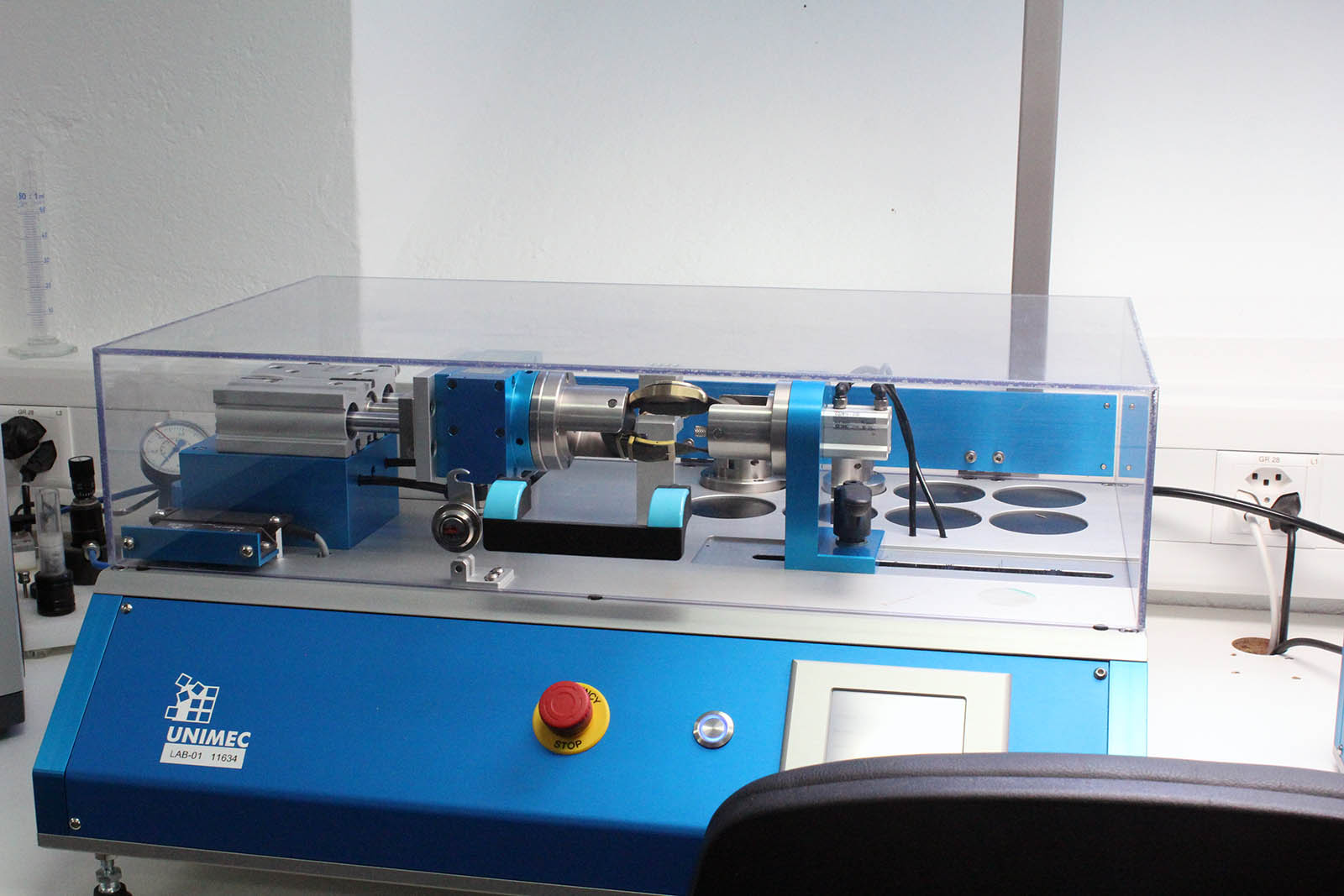

Unlike COSC certification that only tests movements, the Montblanc 500-hour test subjects each complete watch to five sets of tests over three weeks.

According to Montblanc, all watches equipped with “manufacture” movements are subjected to the 500 hour test that covers performance, accuracy, overall function, general performance and water-resistance.

The production building in Le Locle

Given that it was introduced when former Jaeger-LeCoultre chief executive Jerome Lambert took over Montblanc, the test was perhaps inspired by the 1000 hour test that was once a distinguishing feature of the Jaeger-LeCoultre Master Control line of watches.

The battery of tests include:

Winding performance – four hours: Assesses the self-winding performance of the watch.

Accuracy – 80 hours: Monitors the rate in all positions.

Cyclotest – 336 hours: Tests the overall functioning of the watch by subjecting it to strong rotational motions that simulate real-life conditions.

General Performance – 80 hours: Tests the functions and complications, such as winding efficiency, chronograph’s timing accuracy, push-piece handling and calendar operations, in all positions.

Watertightness – two hours: Tests the water-resistance in terms of air tightness, humidity and submersion.

Manufacture movements are tested in five positions

The one-metre drop test

The four-hour Cyclotest that tests the overall functioning of the watch in a variety of simulated wrist rotational conditions; this machine tests 48 watches at a go

A tensiometer stretches the straps to extremes

Keeping the flame alive at Minerva

A short drive away from Le Locle is the town of Villeret, the home of Minerva. Another brand that was established in the town was Blancpain, albeit a century earlier, in 1735.

Minerva was set up by brothers Charles and Hyppolite Robert in 1858, starting out as an établisseur, a workshop that finished movement blanks, or ebauches, and assembled them into complete watches before sending them to watch merchants.

The company subsequently changed hands on a few occasions but its most prominent owners were the Frey family, who took over the company in the 1930s. They ran the company for most of the 20th century, turning it into a darling of watch aficionados in the 1990s thanks to old school movements and designs. In 2000, the Freys sold the company to controversial Italian tycoon Emilio Gnutti, once a substantial shareholder in Telecom Italia, who in turn sold it to Richemont not long after.

From 1910s through to the 1920s, the company produced watches under a host of brand names, such as Mercure, Ariana, Rhenus and Tropic, as was common at the time.

Most of these labels were named after gods and goddesses in Greco-Roman mythology, including Minerva, the Roman version of Athena, the Greek deity of wisdom and strategy in war.

Minerva is often depicted wearing a helmet and a spear; within every Minerva chronograph movement is a miniature representation of Minerva’s spear: the trademark arrowhead on the tip of the chronograph hammer.

Though it is widely referred to as the “devil’s tail”, a Montblanc representative was swift to clarify that it has absolutely nothing to do with the devil, and the feature is indeed a tribute to Minerva.

Examples of Minerva’s spear

A chronograph story

Minerva played a crucial role in the development of the chronograph, having developed notable innovation for early stopwatches. The brand was one of the pioneering chronograph makers in the modern day, producing its first chronograph movement, the cal. 19-9, in 1908, and then in 1911, unveiled stopwatches that could measure a fifth of a second.

Minerva was also amongst the first to introduce a high-frequency chronograph movement when it introduced a stopwatch that could measure down to a hundredth of a second in 1916. Then in 1923, it introduced the legendary cal. 13-20, a beautifully designed monopusher, column wheel chronograph with a distinctive V-shaped bridge.

A 1/5 of a second chronograph from 1930 with a white enamel dial.

A 46mm, monopusher chronograph with the cal. 19-09CH

A midcentury wristwatch that inspired the design of the new Heritage collection launched at SIHH 2019

The Great Depression wrought changes in ownership and in 1935, Minerva was taken over by employees Jacques Pelot and Charles Haussener; Andre Frey was Pelot’s nephew. Under their leadership, the brand became the official timekeeper of the 1936 Winter Olympics in Garmisch, which set an important precedent by establishing stopwatches and other measuring instruments as a key pillar of its business.

The company also became a maker of precision instruments and wristwatches for the military, with its early aviator’s chronographs being particularly desirable today. And in the later decades of the 20th century, it continued supplying measuring devices to clients outside the watch industry, which kept the company afloat during the Quartz Crisis.

Where the magic happens

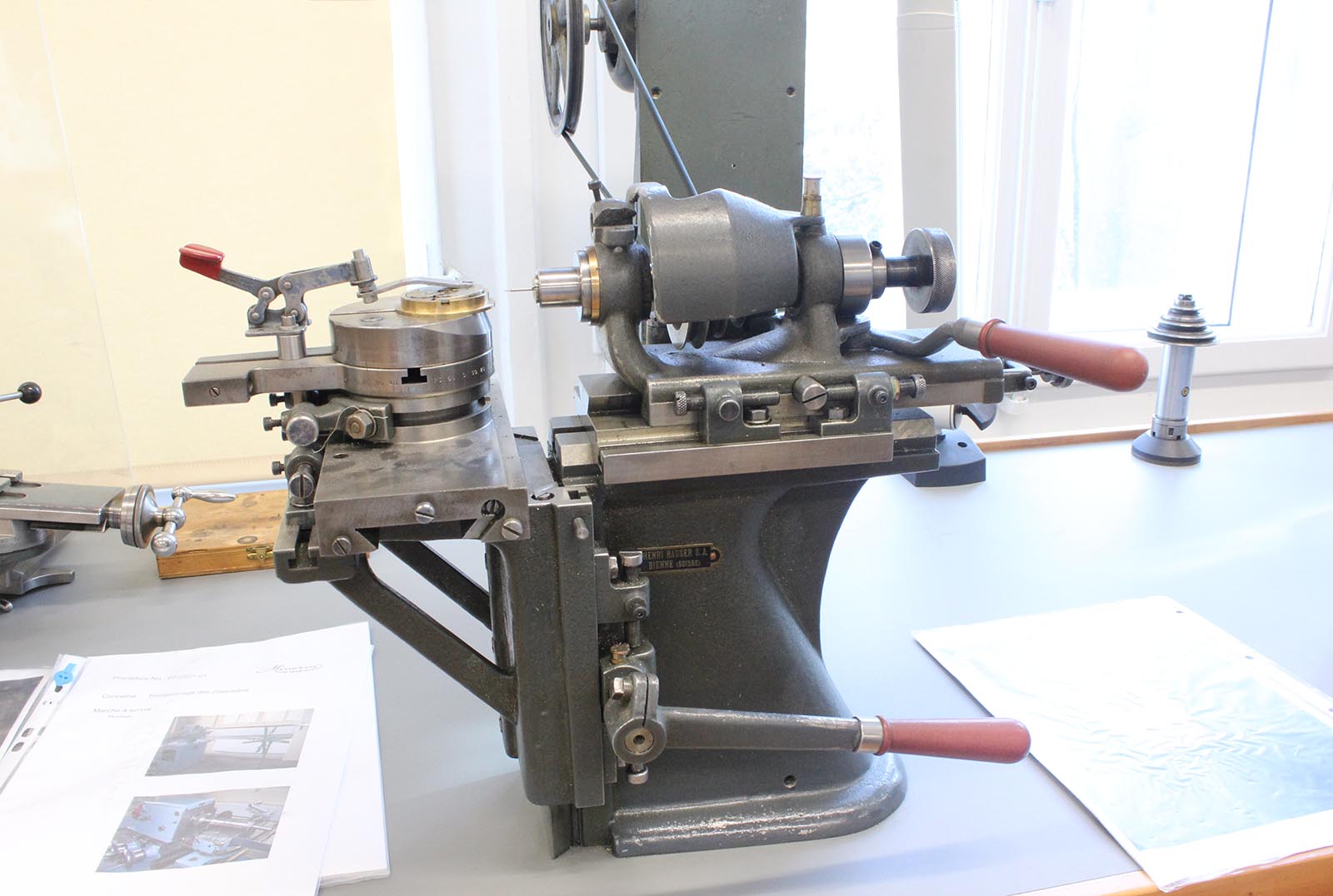

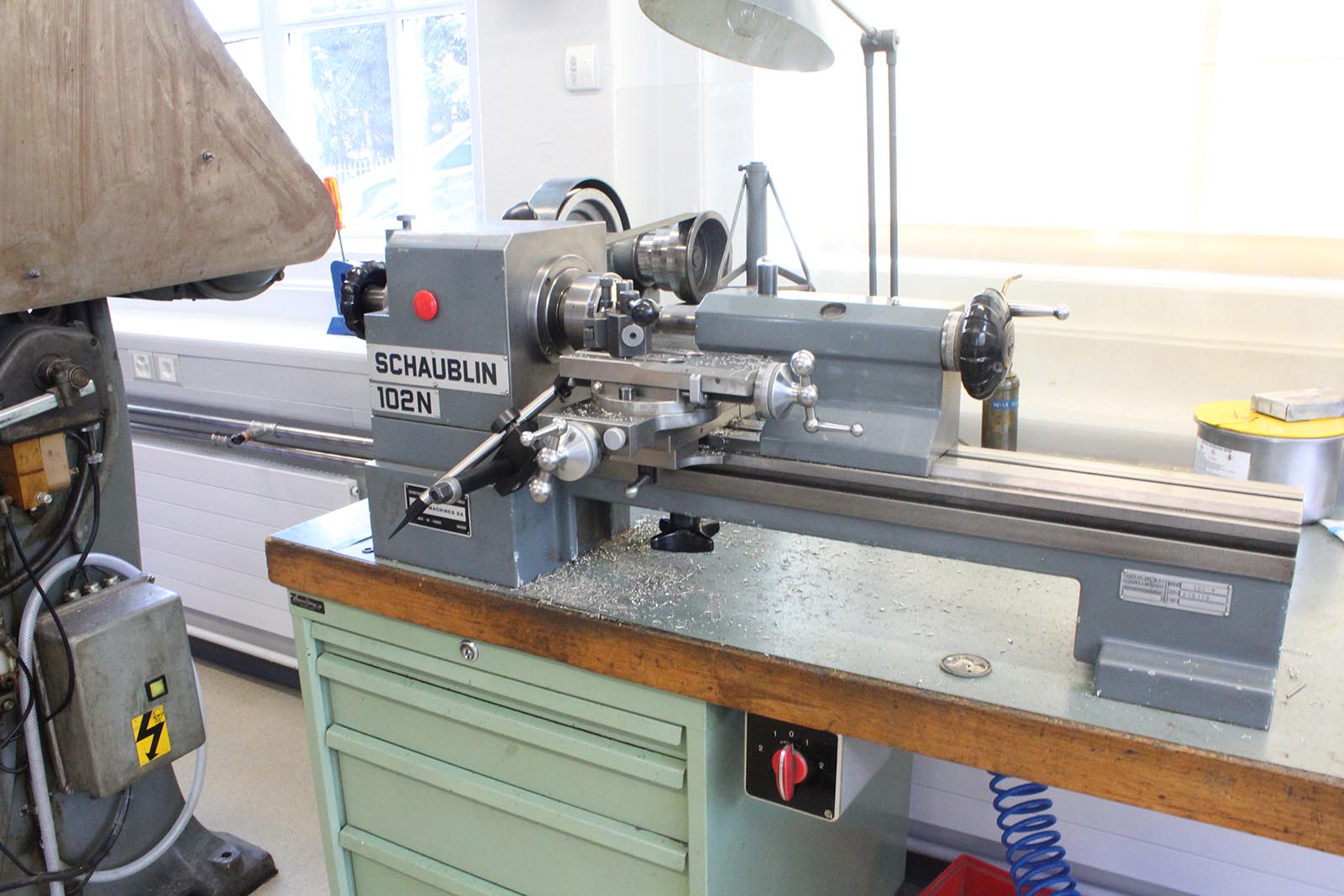

The Villeret facility, which employs 30 watchmakers including seven complications specialists, handles the development of all top-tier watches. Machines from the early 20th century share the floor with modern CNC and CAD machines.

Despite its small output, Villeret is pretty much vertically integrated. The workshop produces most components of the movement, including hairsprings, an unusual feat. Subsequent steps in production are also done in-house, including hand-finishing, assembly and casing.

And like many other small scale, high-end watch workshops, instead of an assembly line style production, one watchmaker is responsible for both assembly and casing.

The control panel displaying the coordinates for milling operations

The old machines are notably well-preserved and complete – and entirely functional. Base plates for all Minerva chronographs are still created using an antique stamping machine.

The press for base plates

The precious, decades-old stamping dies are arranged by calibre

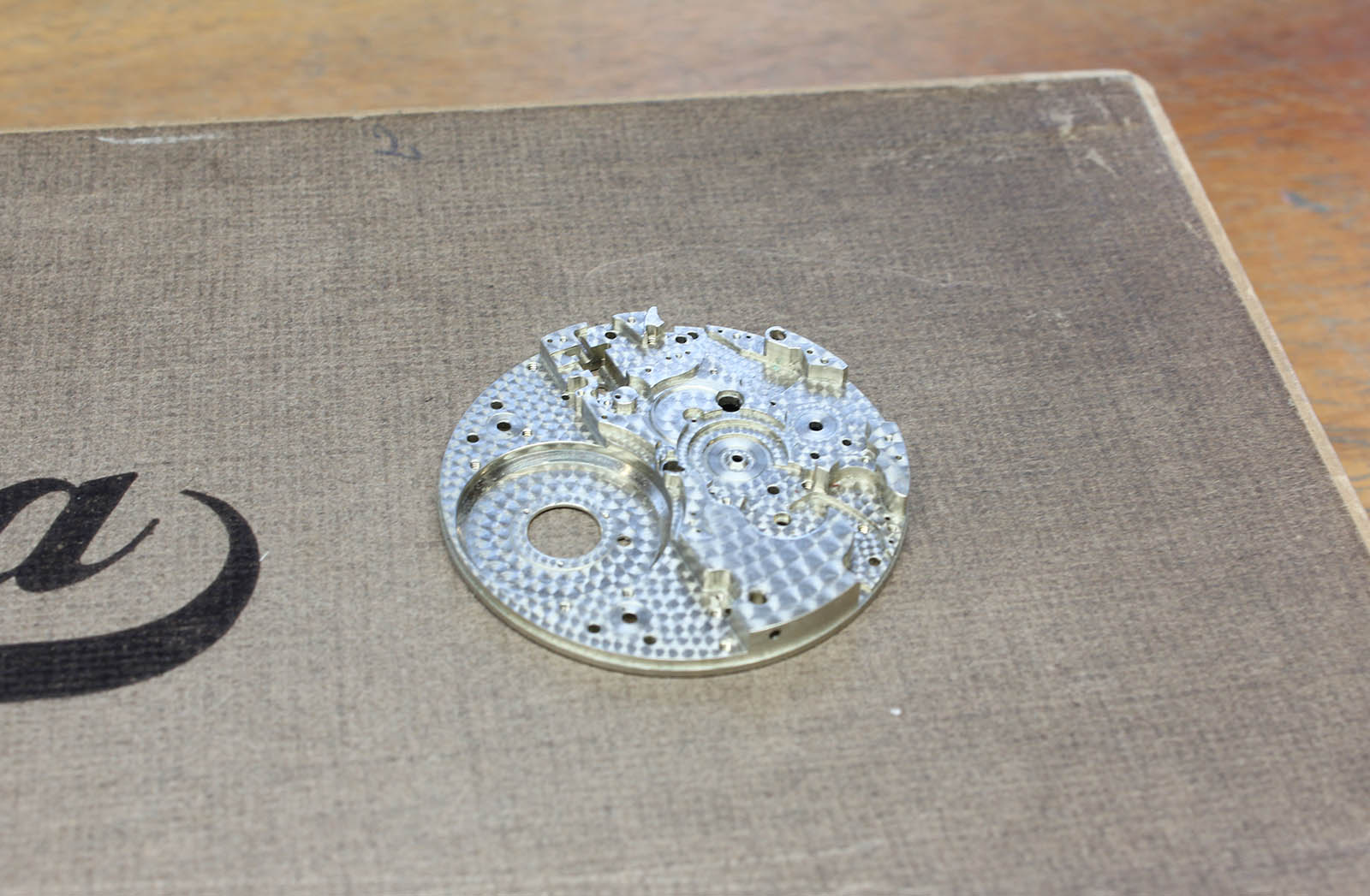

The manufacture only uses German silver for their base plates as it is more rigid and durable than brass, and oxidation creates a pleasing patina on the metal. A standard Minerva chronograph requires two days of assembly while the some of the most complicated movements can take up to eight weeks.

A German silver base plate finished with perlage

Manually applying perlage to a base plate

A polished pallet fork

A watchmaker polishing a component using a piece of wood from the Gentian tree, the traditional material for polishing bevelled edges, or anglage

Perhaps one of the most revelatory aspects of the manufacture is that it has been producing its own hairsprings for the past seven years, albeit on an artisanal scale. Within Richemont, only two other brands boast this capability, A. Lange and Söhne and Jaeger-LeCoultre, both of which produce hairsprings in larger numbers.

Vibrating an in-house hairspring

Set up by a retiree from Nivarox, the hairspring department gave Montblanc the ability to construct unusual oscillators, such as the double cylindrical hairspring found in the Villeret Tourbillon Bi-Cylindrique. Naturally, in-house hairsprings are reserved solely for the watches produced at Villeret.

Fitting a stem and crown into an 1858 pocket watch

Freshly completed Star Legacy Suspended Exo Tourbillons

The view from the Villeret penthouse; partially visible at bottom left is the original Minerva building that’s painted pale green with red windows

Treasures in the attic

Apart from the Quartz Crisis, another catastrophe that the Villeret manufacture weathered was a 1973 fire that wiped out a good deal of the facility.

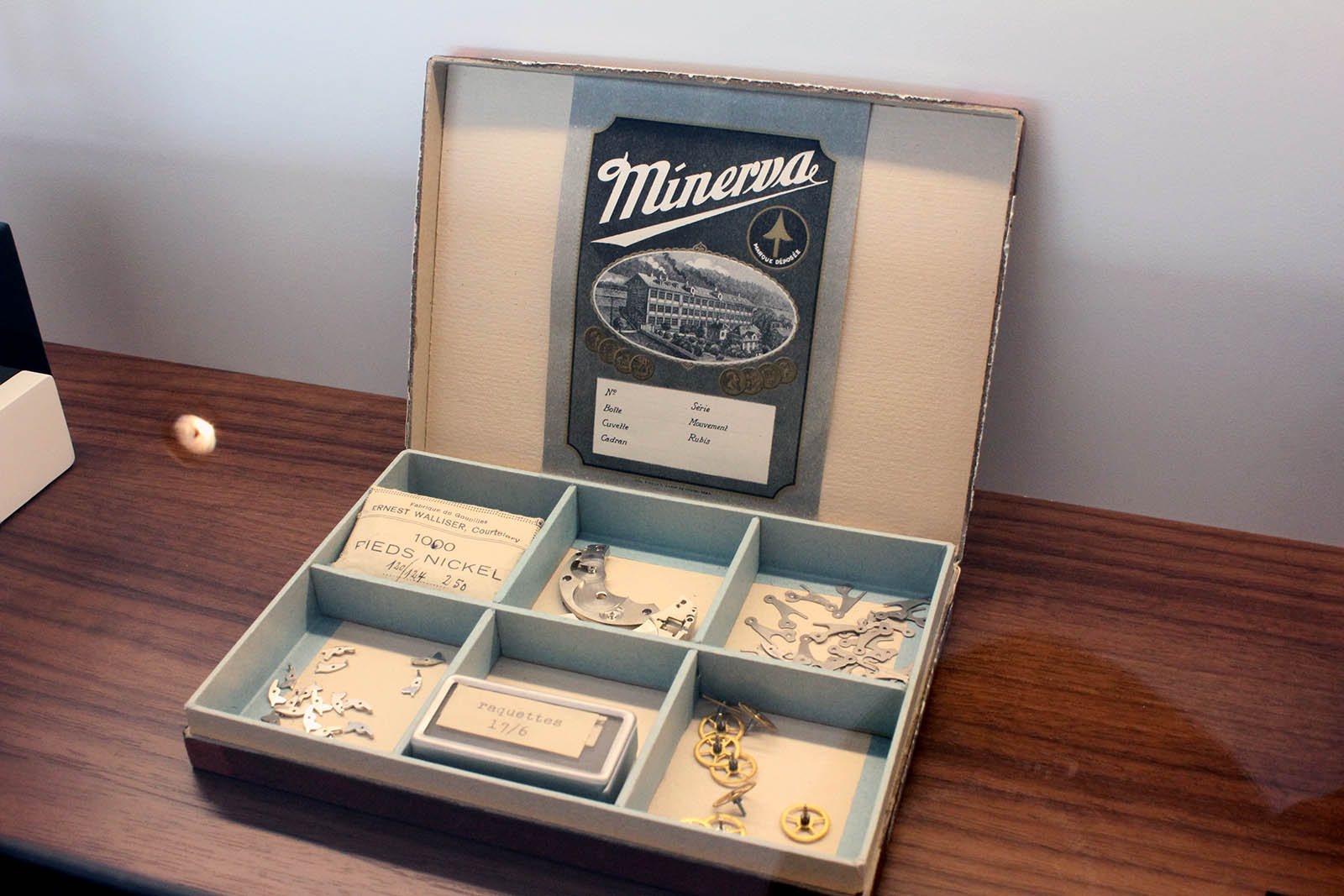

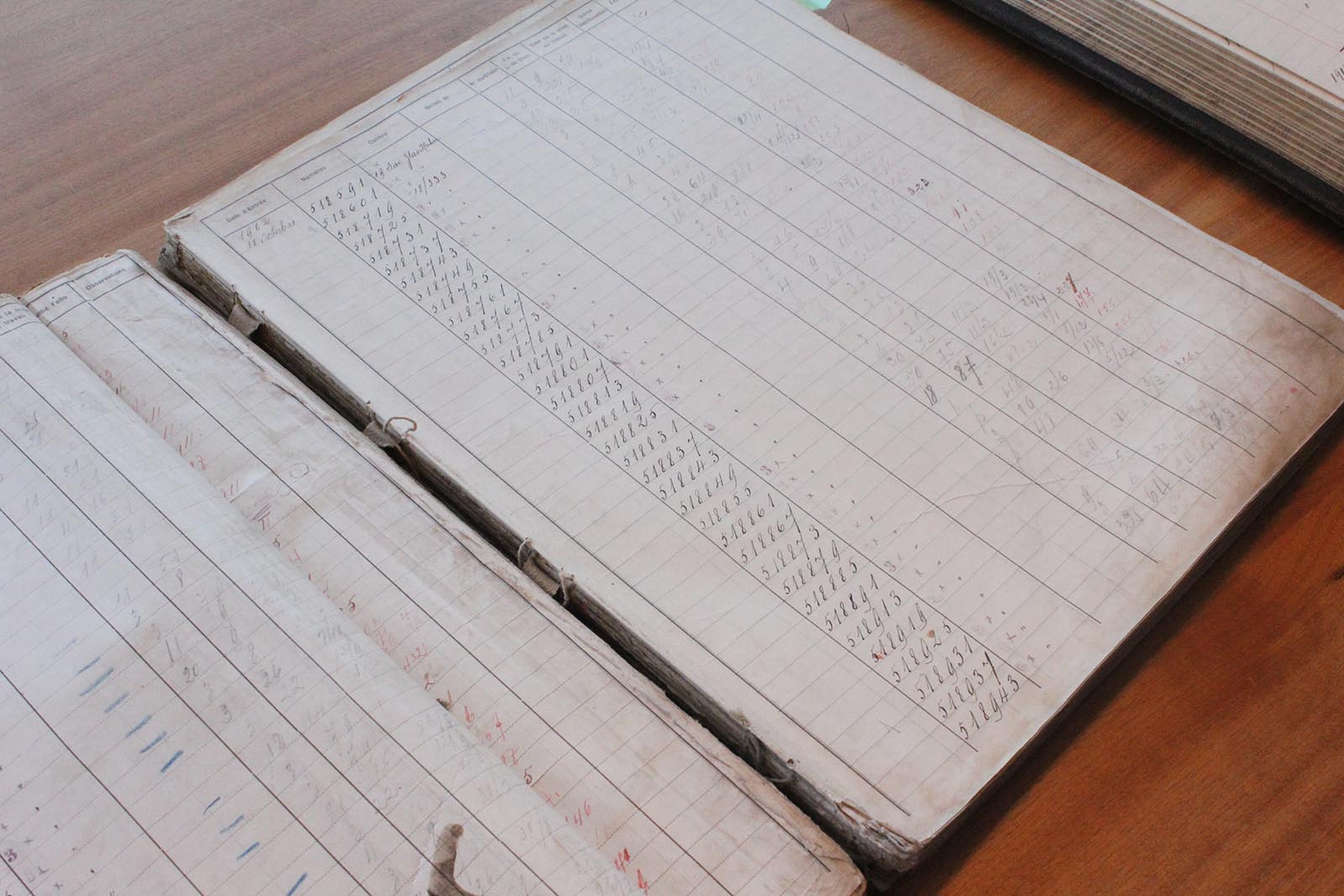

But after the Richemont acquisition in 2008, a search of the factory turned up shards of Minerva’s past, some of which are surprisingly well preserved. A few of this discoveries are currently on display at the top floor of the manufacture, including cabinets filled with unused movement components and dials – mostly pristine and “new old stock” – as well as sales ledgers from the company’s early days.

Ledgers from long ago

A trove of components

Enamel dials in their original wax paper wrapping

Making sense of it all

Montblanc is now a brand on the rise, especially with its watch division. Among the varied watch brands within Richemont, it suffices to say that Monblanc has created one of the clearest solutions to the dilemma between artistic integrity and commercial viability.

While credit largely goes to hard-charging former chief executive Jérôme Lambert and design chief Davide Cerrato for catapulting it to the next level, that progress would be impossible without the halo of Minerva, with all its historical nous. At the same time, the industrial production of Le Locle and ValFleurier have given Montblanc the economies of scale necessary to produce enough accessibly priced watches to make the artisanal output of Minerva viable.

It’ll take more time for the Montblanc name, still mostly known as a pen maker, to catch up with the quality of production at Minerva, but the ingredients are all there in Villeret.

Back to top.