Insight: Patents in Watchmaking

Protecting ideas great and small.

Patents in watchmaking are often brushed over by the brand themselves, except when tallying them in marketing material. But they are important, and can be foundational to a brand, as George Daniels’ famed co-axial escapement is synonymous with Omega.

But there is a great deal more in watchmaking that can be protected with a patent than a lubrication-free escapement. A large proportion of the parts that make up a watch – from case materials to time-display mechanisms – can be patented, and often are. That begs the question: what exactly can be patented?

The common obstacle encountered by a would-be inventor is that patents are notoriously difficult to secure, especially if applied for without specialist help. Going from application to approval of a patent often requires several years, and approval is not a certainty. Gaining a patent hinges on three criteria: the invention in question must be new, non-obvious, and useful.

Beyond the necessary knowledge of prior inventions – in order to prove the patent-pending idea is new – the incredibly specific wording required for patents can be daunting to an independent applicant, so it usually falls to a patent attorney to lead the application process. But patents can be lucrative for an inventor, especially for an innovation targeted at the consumer, which is why new patents are registered every day. The United States Patent and Trademark Office, for instance, received just under 670,000 patent applications in 2019, and granted a little over 391,000.

The waterproof Oyster

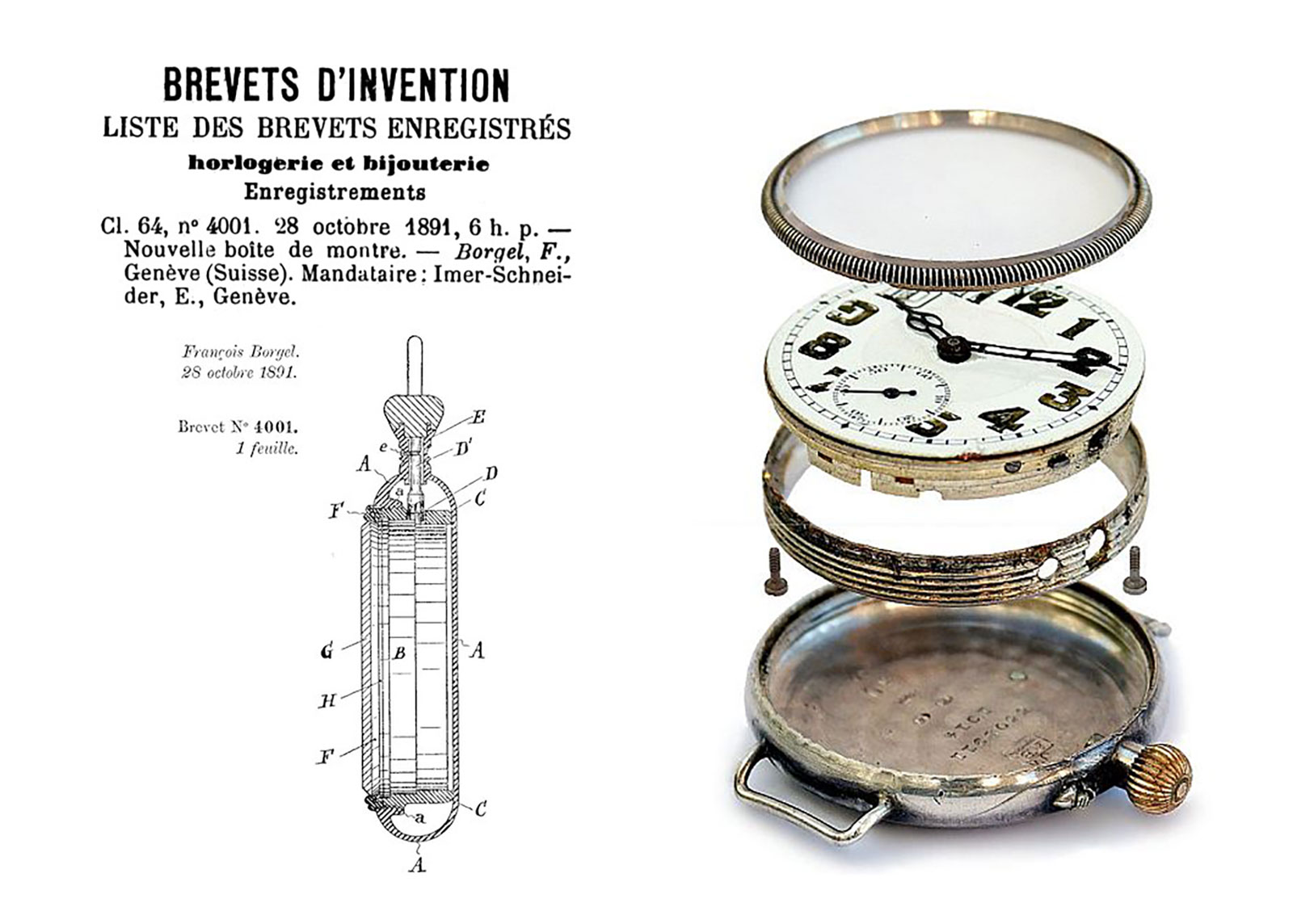

Consider the Rolex Oyster case, one of the watchmaking’s finest examples of an innovative patent that benefits the consumer. Though well known today as a Rolex invention, its history can be traced back to 1891, when the threaded-screw case system was patented by Francois Borgel as Swiss patent CH4001. His water-resistant watch case was fairly complex in comparison to the modern-day norm: the Borgel case called for the dial, movement, bezel, and crystal to be inserted into a carrier ring that was then screwed into the case.

Borgel’s idea was certainly a big step forward in terms of protecting a watch movement against water but it wasn’t perfect. It still suffered from vulnerabilities where water could enter the case, most notably the crown. Borgel attempted to render these ingress points more resistant, but the significant breakthrough came in 1925, when watchmakers Paul Perregaux and Georges Perret developed a screw-down crown and stem, registered as Swiss patent CH114948.

The Borgel patent CH4001 (left), and an exploded view of a Borgel watch case. Images – VintageWatchstraps.com © David Boettcher

A year later, Rolex founder Hans Wilsdorf bought the Perregaux-Perret patent and registered it in the United Kingdom as British patent GB260554, creating the Rolex Oyster watch case. And in 1927 the patent made history when Mercedes Gleitze became the first woman to swim the English Channel – while wearing a water-resistant Rolex Oyster that naturally kept good time throughout her crossing.

[Horological scholar David Boettcher delves into the history of the Borgel case in great detail on his website, which is worth a read.]

A variant of the first Rolex Oyster, circa 1926 (left), similar to what Mercedes Gleitze would have worn on her record-setting swim, which was covered in British newspaper Daily Mail (right). Images – Rolex

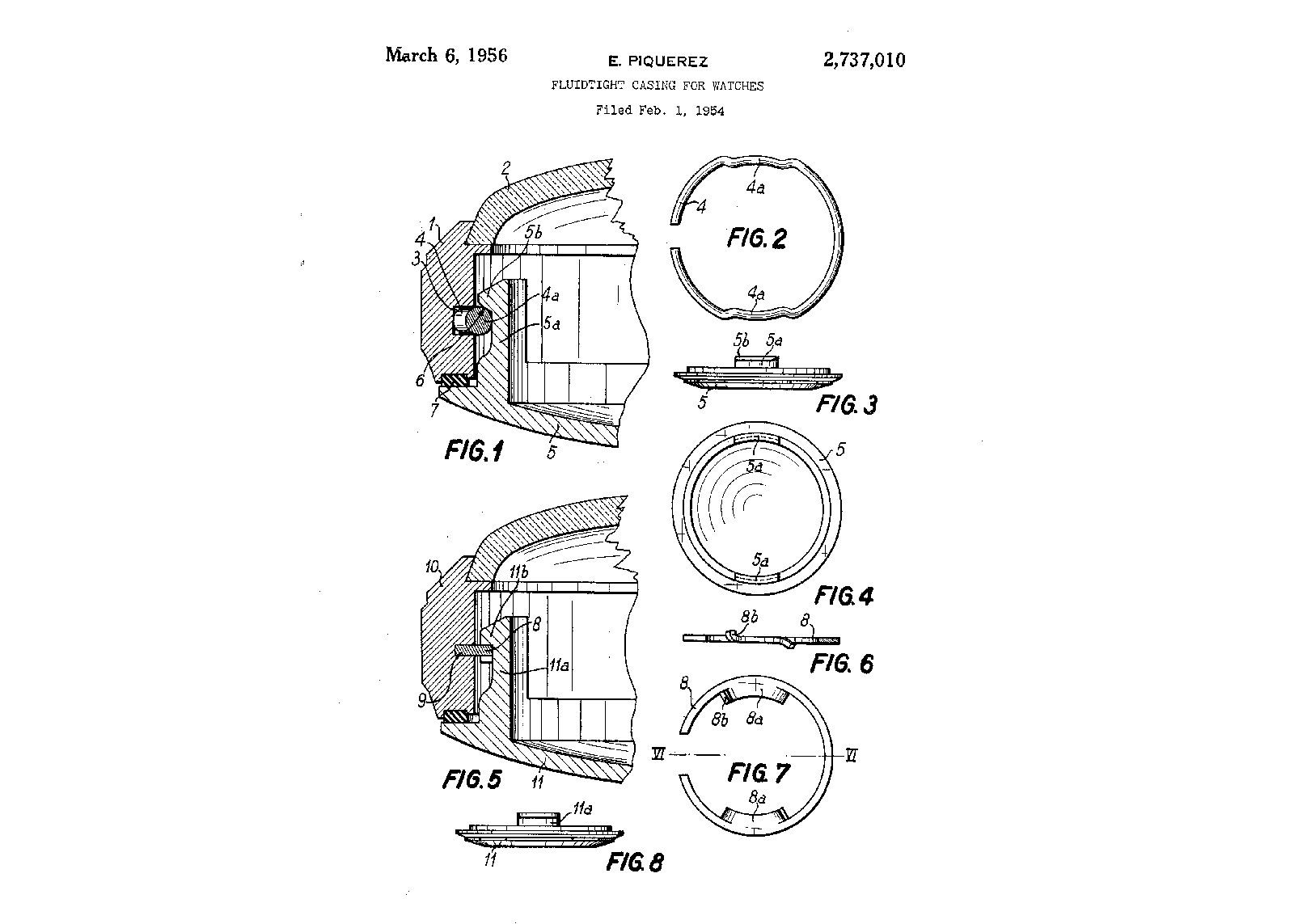

The simplicity and effectiveness of the Oyster construction has made it the de facto standard today. There were attempts to challenge the Oyster construction over the decades, with varying degrees of success. Many case makers attempted to invent their own systems for water resistance, amongst them the well-known Super-Compressor invented by case maker Ervin Piquerez (Swiss patent CH2737010X), made famous by the double-crown dive watches of the 1960s and 1970s.

Since patents have terms of 20 years from the date of filing, these water-resistant case patents have long expired. Most watch manufacturers today no longer use Borgel’s method of sealing the movement into the case, or any other for that matter. Instead they employ the same system as the Oyster, where the rim of case back is threaded, allowing it to screw into the case.

In the two decades that Borgel’s patent was in force, other manufacturers devised and patented their own water-resistance solutions, making it more difficult to create an alternative that was truly novel and innovative, especially one superior to Borgel’s. The legacy of Borgel’s patent shows the potential of a truly innovative patent, and makes the case for setting a high bar in granting a patent.

The patent diagram of the Ervin Piquerez water-resistant watch case. Image – Google Patents

Patent or trademark?

While the constituent parts of a watch – case, balance, winding mechanism and so on – can be patented, can the sum of the parts, the entire watch in other words, be protected by a patent as well? The answer is no.

A watch as a whole cannot be patented, but its constituent parts or mechanisms can be protected. Case shapes – which are ornamental designs for a functional object – can be protected by a design patent. This has a shorter term than a regular patent, of only 15 years from the date granted (the term was 14 years prior to 2015). Other intangible aspects of the watch, such as names and logos, are typically protected with a trademark.

So while the Rolex Oyster case construction was once protected by patent, the Rolex crown logo is protected as a trademark. Though trademarks have terms of only 10 years, they can be renewed for additional 10-year terms indefinitely, which is why the crown emblem remains protected till today.

Hamilton, which is owned by Swatch Group, took legal action against American brand Vortic in 2018, alleging trademark infringement of the Hamilton brand. Vortic sells wristwatches equipped with antique Hamilton movements and dials, leading Hamilton to argue a “likelihood of confusion” between the two brands. In short, Hamilton alleged that Vortic’s use of Hamilton-branded dials and movements would mislead buyers into thinking they were purchasing a Hamilton, rather than a Vortic, wristwatch.

An example of a Vortic wristwatch powered by a vintage movement, this being a Lancaster 076 equipped with a 1925 Hamilton pocket watch movement. Image – Vortic

Was Vortic’s use of the Hamilton name misleading? The decision by the New York court was clear – and in favour of Vortic. Advertising its watches under the Vortic brand, the court found that Vortic was clearly disclosing its watches relied on parts taken from vintage pocket watches, and were not Hamilton watches. Hamilton’s basis for its case was based on a single, unverified email that referred a photo of a Vortic wristwatch as a “vintage Hamilton” – which that court ruled to be insufficient.

Trademarks are equally as important as patents, especially since the watch industry is part of the broader luxury-goods business, where brand names reign supreme. Subsequently, watch companies value branding as much as, perhaps even more than, the technology inside their products.

The co-axial escapement

Perhaps the most famous example of an invention protected by a patent was the co-axial escapement invented by George Daniels in the mid 1970s. It took Daniels years to convince a big Swiss watch brand of his invention’s potential, but he finally did sell the patent (EP1045297) to Omega, which debuted its first serially-produced watch equipped with the co-axial escapement in 1999.

Even though the patent expired in 2019, Omega has developed the escapement a long way in the 22 years since its launch, and also produced a great deal of them – well over a million Omega watches with the co-axial escapement have rolled off the production line. The sheer volume, combined with Omega’s persistent marketing of the invention, has made the co-axial escapement an integral part of the brand. Although the co-axial began as a brilliant idea, it has now converged into the Omega brand, which is perhaps why despite the patent expiring in 2019, Omega remains the exclusive manufacture of the co-axial escapement on a large scale, and no rival has attempted to invent a direct replacement.

A co-axial escapement in the Daniels Anniversary wristwatch

R&D

Aside from significant movement patents, there are many patents covering other aspects of the watch filed every year by major companies like Rolex, Swatch Group, and Richemont. From 2008 to 2018, Rolex filed over 70 patents in the United States. Just like any large manufacturer that does its own research and development, Rolex files for more patents than it uses. Apple is another company that does this, but on a far larger scale. Amongst its patents is a camera integrated into the band of a watch.

While some patents are used immediately, others take years to come to market. In 2013 Rolex filed patents for methods of producing one-piece ceramic bezels in two colours (US9458064 and US9434654). In the same year, the GMT-Master II “Batman” was launched, followed by a “Pepsi” bezel on the white gold GMT-Master II.

The “Pepsi” and “Batman” ceramic bezels of the Rolex GMT-Master II. Image – Rolex

And sometimes inventions are installed in existing movements or watches, improving their function in subtle ways. Rolex often updates its movements during their production lifetime – which is typically decades – and occasionally retrofits the improved components into watches that are returned for servicing.

Richard Lee detailed the clutch mechanism in the cal. 4130 found in the Rolex Daytona, illustrating how new technology is progressively integrated into existing movements. One of the key upgrades to the cal. 4130 is the wheel that drives the chronograph seconds hand.

The LIGA wheel in the cal. 4130. Image – Rolex

Using the patented technique of additive manufacturing known as UV-LIGA (US9284654), the wheel is fabricated with integrated, skeletonised teeth that function as tiny springs, allowing it to mesh more closely with the connecting wheel. The result is eliminating the seconds hand “stutter” that occasionally arises when the chronograph is started. Crucially, this isn’t just relevant to the enthusiasts who cares about such esoteric details, but also to the average watch buyer who isn’t aware of its existence, but benefits from the smoother motion of the seconds hand nonetheless.

The use of patents in the watch industry spurs research and typically results in better watches, albeit in subtle ways. It is often the case that patent law applies to an invention is an incremental innovation hardly discernible to the consumer. Consequently, it can sometimes feel like watch brands are doing more marketing than inventing when they tout new technology as the greatest thing ever. But because of the rigorous and consistent nature of patent law, new inventions are generally, well, new. And even if they are invisible to the average buyer – the cal. 4130 is a good example – such innovations do result in tangible, if discreet, improvements in a watch that deserve praise.

Owen Lawton is a student at St Catherine’s College, Oxford, reading materials science. He became interested in watches and the use of materials in watchmaking in his late teens and enjoys applying his studies to the hobby. He shares his photography on Instagram.

Correction March 7, 2021: Patents have 20 year terms from their filing dates, but can only be enforced from the date that they are granted; they are not valid for 20 years from the date of grant. Also, patents cannot be renewed at the end of their 20 year term. And case designs can be protected with a design patent of 15 years, and not a trademark.

Back to top.