The Pursuit of the Perfect Watch Movement at Omega

We chronicle Omega's manufacturing of the Master Co-Axial, and the rigorous testing by the Swiss government's weights and measures agency.

Omega has been working on the perfect mechanical watch movement, working towards a calibre that runs reliably and efficiently for long periods before requiring servicing. This benefits the consumer, who enjoys a superior product, but also boosts Omega’s bottom line by reducing warranty returns. It sounds simple in theory, but the endeavour has taken decades, even with Omega being one of Switzerland’s most accomplished watch manufacturers.

In fact, Omega is one of the handful of watchmakers able to plausibly construct a near perfect mechanical movement. That’s because Omega enjoys enormous scale – production of some 800,000 watches a year – and the fact that its sister company in the Swatch Group is ETA, the biggest maker of mechanical movements in Switzerland. All things being equal, making more movements makes each one better due to increased automaton and economies of scale, which gives Omega tremendous advantages.

It started with an Englishman

The first step in Omega’s pursuit of the ideal movement was the purchase of English watchmaker George Daniels’ Co-Axial escapement, which made it into commercial production in 1999. Conceived as a lubrication-free escapement – no oils to dry up means longer service intervals – the Co-Axial escapement required years of tweaks, plus a tiny drop of lubricant, to get right.

Then came the silicon hairspring, something fellow watchmakers like Patek Philippe and Rolex have also adopted. Resistant to magnetism and temperature changes, as well as easy to manufacture in a perfect form, the silicon hairspring is sometimes regarded as the greatest thing in mechanical watchmaking since, well, ever. Omega christened its silicon hairspring Si14, but it is similar in material to the hairsprings used by its peers.

The Swatch Group, Patek Philippe and Rolex were the key watch industry backers of Centre Suisse d’Electronique et Microtechnique (CSEM), a Swiss research institute that developed the technology to put silicon into watch movements. All three companies have access to the same technology, but each has developed its own design and shape for the silicon hairspring.

Alloys that are completely non-magnetic were the last piece of the puzzle, making their debut in the Aqua Terra >15,000 Gauss three years ago. Patented and still secret, these special metals are used for key escapement components, giving the movement unparalleled resistance to magnetism equivalent to the field generated by a small magnetic resonance imaging machine (MRI) or a neodymium magnet. Though there have been experimental or top-secret military issue watches (like the Ocean 2000 Amag watches IWC made for the German navy’s minesweeping frogmen in the 1980s) that may have had similar magnetism resistance, Omega’s magnetism-proof watches are the first to be produced on such a scale, and more importantly, be robust enough for everyday use.

Mastery of movement production

All these pieces are the crucial elements of the Master Co-Axial, the latest generation of Omega movements produced at a brand new production facility in Villeret, a small town best known for being home to Blancpain and Minerva. Operated by ETA exclusively for Omega, the Master Co-Axial factory is the cutting edge of movement production. Neither art nor artisanal, the Master Co-Axial facility embodies the ruthless pursuit of an exceptional mechanical movement.

Though the Master Co-Axial facility is so hush-hush that no photos are allowed, Omega can’t resist showing off its impressive production line. Just after Baselworld 2016, your correspondent was invited for a look.

White-coated technicians work in an immaculate room, clustered around workstations dedicated to particular steps in the assembly process. The facility does not merely seem spick and span, it actually is. The assembly workshop is a ISO 2 class cleanroom, with less than 100 particles measuring 100-micrometers or more in every cubic metre.

An automated system transports movements-in-progress down the assembly line on a miniature conveyor belt, with each movement ensconced in a plastic case with an RFID tag. The radio frequency identification device (RFID) tag stores all the necessary information about the movement, like what components have been put in, and the watchmaker that did it, with each workstation automatically updating the RFID tag as the movement passes through.

High-tech equipment is used during movement assembly, which is done with a combination of watchmakers and automated equipment. For instance, every screw in a Master Co-Axial movement is tightened by an automated screwdriver, wielded by a watchmaker, that is capable to measuring torque, ensuring that all screws are just right.

Once the movements are almost complete – before the winding rotor is put in – they are shuttled over to Contrôle Officiel Suisse des Chronometers, the Swiss chronometer testing institute better known as COSC, which tests the movements (without cases) and certifies those that pass. With a pass rate in excess of 90 percent, COSC’s tests are sometimes criticised for being lax. That is where METAS comes in.

The science of impartial measurement

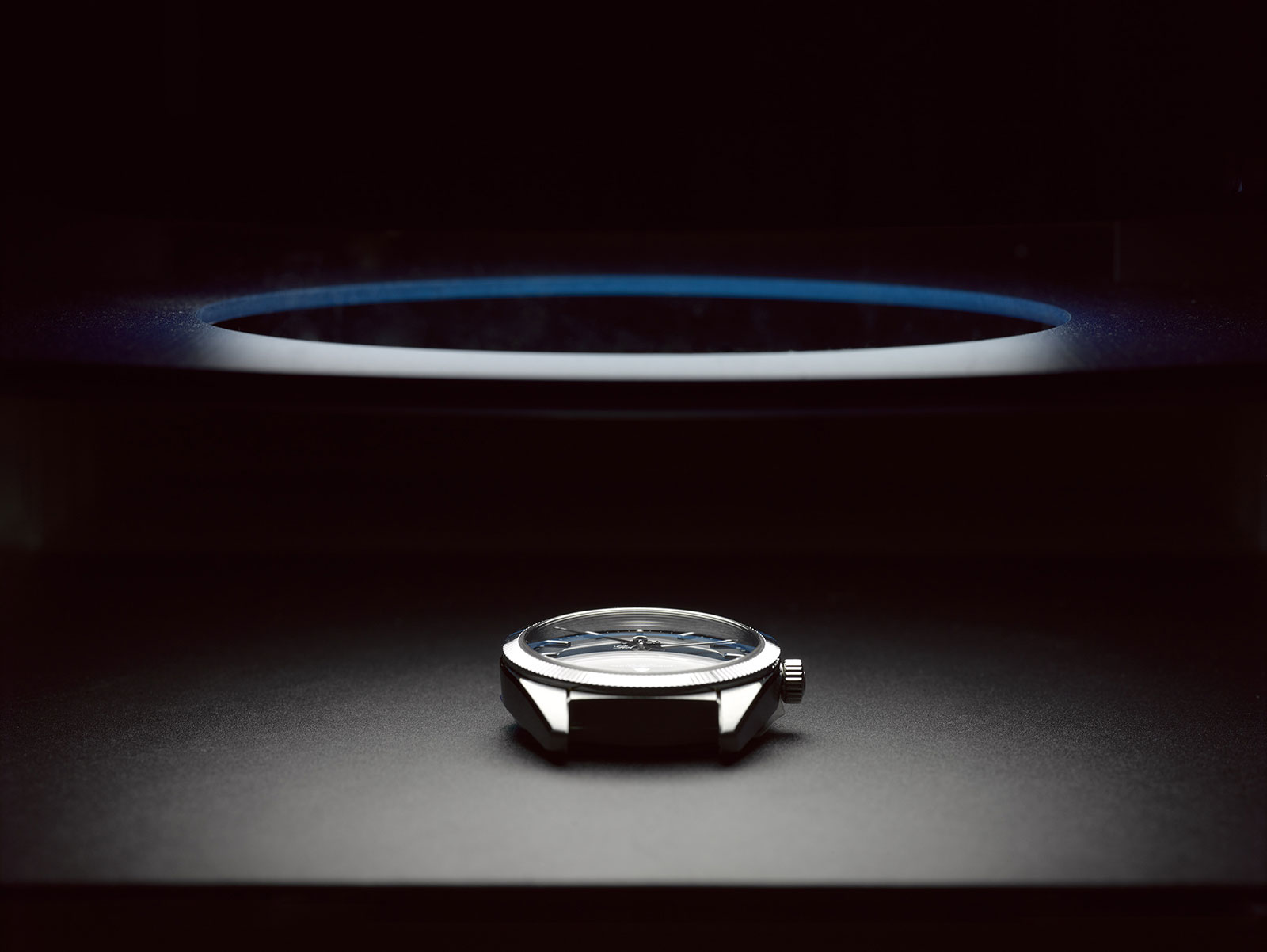

After passing COSC certification, the movements are sent to Omega’s headquarters in Bienne and assembled into complete watches. They are then sent down the corridor to the METAS lab inside Omega’s headquarters in Bienne. METAS is the Swiss Federal Institute of Metrology, a government institution that is in charge of everything related to weights and measures in the Alpine nation. Amongst the jobs METAS takes on is the calibration of the radar guns used by the Swiss traffic police, ensuring that a breach of the speed limit is actually a breach.

METAS inked an agreement with Omega in 2014 that outlined a new testing and certification process for wristwatches, one will gradually be applied to all Master Co-Axial watches, though the Globemaster is so far the only model to received METAS certification. Omega promises that by 2020, all its mechanical movements equipped with the Co-Axial escapement will be METAS certified.

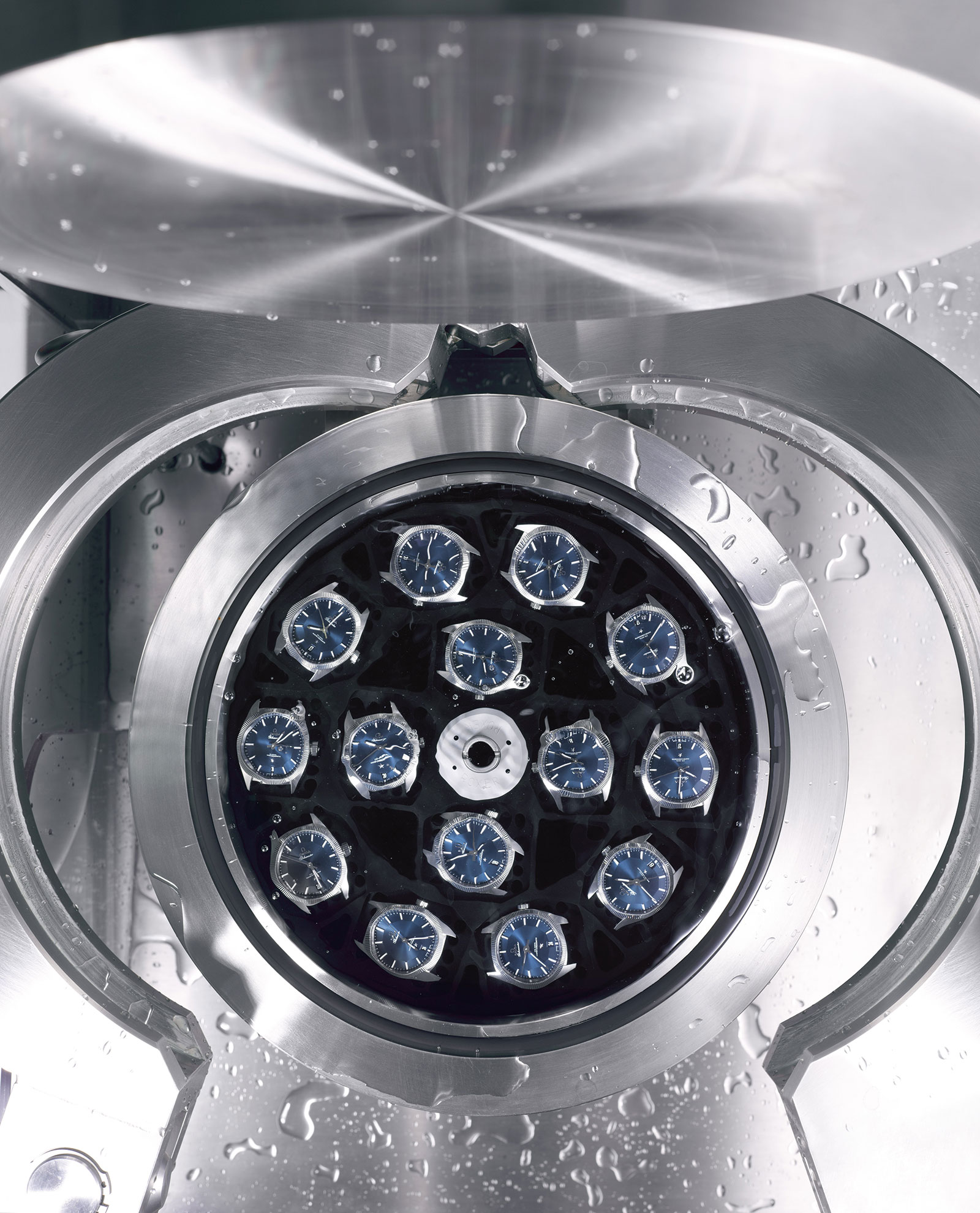

The METAS test is all encompassing, testing everything from water-resistance to power reserve, and of course timekeeping – in a simulated 33 degree Celsius environment, which is the temperature of a watch on a clothed wrist anywhere in the world. Testing extends to timekeeping with the mainspring wound down, with each watch tested in six positions twice, first with the movement fully wound, and then when the mainspring is only wound by a third.

But because Master Co-Axial movements boast exceptional magnetism resistance, METAS also ensure the movements live up to that claim. Watches are subject to a magnetic field of 15,000 Gauss, generated by a 1.5 tonne magnetic supported by steel beams screwed into a structural wall. Because the METAS testing is so stringent and specific, much of the testing equipment had to be built from scratch (including the gargantuan magnet).

Probably the largest magnet in watchmaking

The criteria laid out by METAS dictate that watches must keep time to within 0 to +5 seconds a day during testing, regardless of what they are being subjected to. Omega and METAS developed this strict limit that only allows for a gain in time to ensure that the wearer of a METAS certified watch is never late, since the watch can only run fast.

Measuring timekeeping on individual watches is done with high-speed cameras that photograph the hands at fixed intervals and checked against the reference UTC time signal received from METAS headquarters via a dedicated antenna on the roof.

All the tests are conducted by Omega employees, but watchful eyes are behind the next wall, literally. Inside the testing lab is a room staffed by a permanent staff from METAS whose job it is to audit the testing. With METAS being a Swiss government agency, the impartiality is rigorous – everything inside the METAS room, right down to the chairs and stationery, is supplied by METAS. Each week the METAS watchmen do a random check on 20 to 30 watches, seizing them for tests inside the METAS room, which is only accessible by METAS staff.

The robotic arm that retrieves trays of movements for testing

The way of the future

Building the factory to construct high-tech movements on such a large scale, and putting together the testing facilities, is an investment that cost Omega millions. Though the manufacturing and testing arguably lacks soul, the scale and industry of it is reassuring, particularly since a wristwatch, strictly speaking, is a mechanical object intended to perform a well-defined task: keep good time for a long time.

Because Omega’s size is almost without peer in Swiss watchmaking, its smaller competitors will be left behind in terms of technology when it comes to watches in the entry-level to mid-range. Producing movements comparable to the Master Co-Axial is impossible, without sufficient scale.

Naturally, old school haute horlogerie watchmakers will still dominate the higher plane of hand-made – but often unreliable – complicated watches. But such watches are not timekeepers in the most exacting sense of the word, rather they are, or hope to be, mechanical art. Omega meanwhile is pulling ahead, making tremendous numbers of watches with high tech mechanical movements that do the job better for longer, and at relatively affordable prices.

Back to top.