Insight: Fine Watchmaking Market Map in 2022

Examining how many people it takes to build a watch.

For almost as long as I’ve been interested in watches, I’ve tried to find an objective way to visualise the stratification of the various luxury watch brands. I’m as fascinated by the process of watchmaking as much as the products themselves, and I wanted to find a way to differentiate brands based on the production techniques they employ, yet do so objectively.

I believe you can tell a lot about a brand’s values and capabilities by looking at their methods, but it can be difficult to penetrate the smoke and mirrors of luxury watch marketing to see what’s really going on behind the curtain.

An objective measure: watchmaker-hours per watch

In my review of the Saxonia Thin last year, I used the metric “watches per watchmaker” to illustrate the economics of A. Lange & Söhne. While this is not a perfect metric, it is simple and quantitative, and crucially, it can often be derived from publicly available information.

Taking this analysis one step further, I added Swiss, German, and Japanese national statistics for working hours to calculate the maximum possible number of watchmaker-hours per watch for more than 50 luxury watch brands.

The start of the map, the Saxonia Thin

How to interpret this metric

The watchmaker-hours metric is not the number of hours that a watchmaker spends on every watch. Rather, it’s the theoretical maximum number of hours that a brand’s watchmakers could possibly spend with each watch. This workrate can be viewed as a simple proxy for the amount of human involvement that each individual watch can get during the production process.

For example, Ferdinand Berthoud is able to invest up to 643 watchmaker-hours in each watch. This is the ceiling; the actual number of hours that a watchmaker spends with each watch will be somewhat less, though it will still be a substantial number, which makes sense given that each of the brand’s watches receives more than 100 hours of hand finishing alone.

The peak: 300+

At the highest level of watchmaking, brands produce fewer than five watches per employee per year, resulting in an average of 834 watchmaker-hours per watch across these 15 brands. Collectors often refer to brands in this category as “independents” but this term lacks precision; not all of these brands are truly independent, while some industrial brands further down the list are.

With production organised around a high degree of hand craftsmanship, output is naturally constrained by the time it takes to produce each watch, ensuring limited production. To put this in perspective, the 15 brands shown above make less than 500 watches per year, combined. In contrast, Rolex makes more than 2,000 watches every day.

The Sylvain Pinaud Origine shows what is possible with artisanal methods

In this category, watches are sometimes referred to as “handmade”, but this term is a bit of a misnomer. With a few exceptions, these watches begin life like any other, conceived using CAD software, with the larger components like main plates and bridges produced using CNC lathes, electro wire erosion, and other modern methods.

It’s what happens next that elevates these watches above the rest of the industry. Wheels and pinions are often produced using vintage manually operated lathes, and dials often benefit from hand-turned guilloche. In terms of finishing and complications, black-polished steel and inner angles are the norm, as are exotic complications (like a remontoir) and unusual escapements.

With such small annual production, most of these brands produce just one or two different movements and models. The outlier is Greubel Forsey, which has achieved the scale (around 115 people) needed to maintain production of several different models and complications including a perpetual calendar, a grande sonnerie, and a world timer.

The Greubel Forsey Hand Made 1

Artisanal-industrial: 100-299

Next we have brands that make, on average, 6-20 watches per employee per year and can invest a maximum of 100-299 watchmaker-hours per watch. This category is dominated, commercially and culturally, by A. Lange & Söhne and F.P. Journe.

At this level, lush hand finishing is expected; black polished steel is common and inner angles can still be found, albeit to a lesser degree. Among brands that maintain a complete collection of different complications (chronographs, tourbillons, minute repeaters, perpetual calendars, and world timers), Lange and Journe are the most artisanal, with capacity for up to 212 and 264 watchmaker-hours for each watch, respectively.

The fine craftsmanship of the latest-generation Lange Zeitwerk

The presence of Montblanc in this category may shock some readers, but this is only the ratio for the brand’s high-end production at its Minerva facility in Villeret which is set up to provide up to 196 watchmaker-hours per watch. In contrast, Montblanc’s core collection likely receives no more than three watchmaker-hours per watch. Part of the value of a market map like this is illustrating where exceptional collections from mainstream brands fit into the bigger picture.

A Montblanc Villeret split-seconds chronograph, something you won’t find at the brand’s ubiquitous airport boutiques

Another outlier in this segment is Urwerk. While most of the brands in this category are limited in output by the time invested in finishing, Urwerk’s finishing is more industrial than that of its peers. Instead, output is constrained by the extra time spent engineering novel displays and case structures.

The curious case of the Urwerk UR-111C

Industrial haute horlogerie: 30-99

The next category contains most of the well-known haute horlogerie brands, including the so-called “holy trinity” of Patek Philippe, Audemars Piguet, and Vacheron Constantin. These brands are regarded with special esteem for having kept the traditions of haute horlogerie alive throughout much of the 20th century. But as the map suggests, the ceiling for what is possible in fine watchmaking has risen significantly along with the growth of the luxury category over the past 30 years.

Many of the brands in this category have mastered the art of producing well-finished watches at industrial scale. This involves the use of machines for most of the finishing, embellished with hand finishing in key areas that are likely to have the greatest visual impact. A few of these brands flirt with inner angles, but this is uncommon; black-polished steel is rarely seen.

Worth noting is Patek Philippe, which employs 1,600 staff and produces about 68,000 watches per year, suggesting a maximum of 38.6 watchmaker-hours per watch. Looking at Patek’s mechanical watch production only, this number gets closer to 50 but still lags behind most rivals. This is important because it helps explain some of the choices the brand makes in its finishing.

For example, many collectors lamented the absence of any sharp inner angles on the new 5236 perpetual calendar. But the fact is that an average of less than 50 watchmaker-hours per watch is just not enough to add these kinds of sought-after flourishes to every watch, forcing the brand to ration these embellishments to their more elite pieces. While the absence is notable, good finishing is about much more than just inner angles and Patek’s movements remain at or near the top of this category in terms of overall quality.

The business side of the ref. 5236P

In contrast, Audemars Piguet currently produces about 48,000 watches per year with about 2,000 staff (up to 72.9 watchmaker-hours per watch). Even this impressive number requires rationing of inner angles, though they can be found abundantly relative to Patek.

Audemars Piguet recently announced plans to increase production to about 65,000 watches per year by 2027. It will be interesting to see how the brand meets these growth targets; were they to achieve this increase in volume with their current headcount, it would dilute their workrate closer to where Patek Philippe is today.

The gold winding mass of the Audemars Piguet cal. 4409 is finished by hand, with sharp inner angles, while the majority of the movement bears a machine finish (a very well done machine finish)

An outlier in this category is Richard Mille, a brand that stands out not only for its high average retail price of US$226,000, but also for outsourcing the production of most of its movements to external suppliers. Though Richard Mille recently introduced its first in-house movement, the CRMC1 chronograph, most of the brand’s watches rely on movements from Vaucher and Audemars Piguet Renaud & Papi (APRP).

These movements are manufactured and finished by their respective suppliers, before being assembled, tested, and cased at Richard Mille’s own facility. It means that the watchmaker-hours metric is undercounting the effort that goes into a Richard Mille watch. But the central question for this map is whether enough extra watchmaker-hours are spent by third parties to cause the brand to change categories.

For that to be the case, APRP and Vaucher would need to employ more than 100 staff solely dedicated to Richard Mille’s movements. I think it’s unlikely that these suppliers require this many staff just for Richard Mille, so I’m confident the brand is categorised appropriately alongside peers like Audemars Piguet and Parmigiani.

An old-school Richard Mille RM002 with an APRP movement

Industrial fine watchmaking: 10-29

This was the most surprising slice of the market. From Bulgari’s ultra-thin record-breakers to Ulysse Nardin’s constant force Ulysse Anchor escapement and Nomos’ playful Bauhaus designs, these brands do things their own way.

Though this segment accounts for only about 200,000 watches annually, the brands that comprise it provide more than their fair share of innovation and creativity. And despite their nineteenth-century roots, many of these brands reject the staid codes of haute horlogerie, focusing instead on pushing the boundaries of industrial watchmaking.

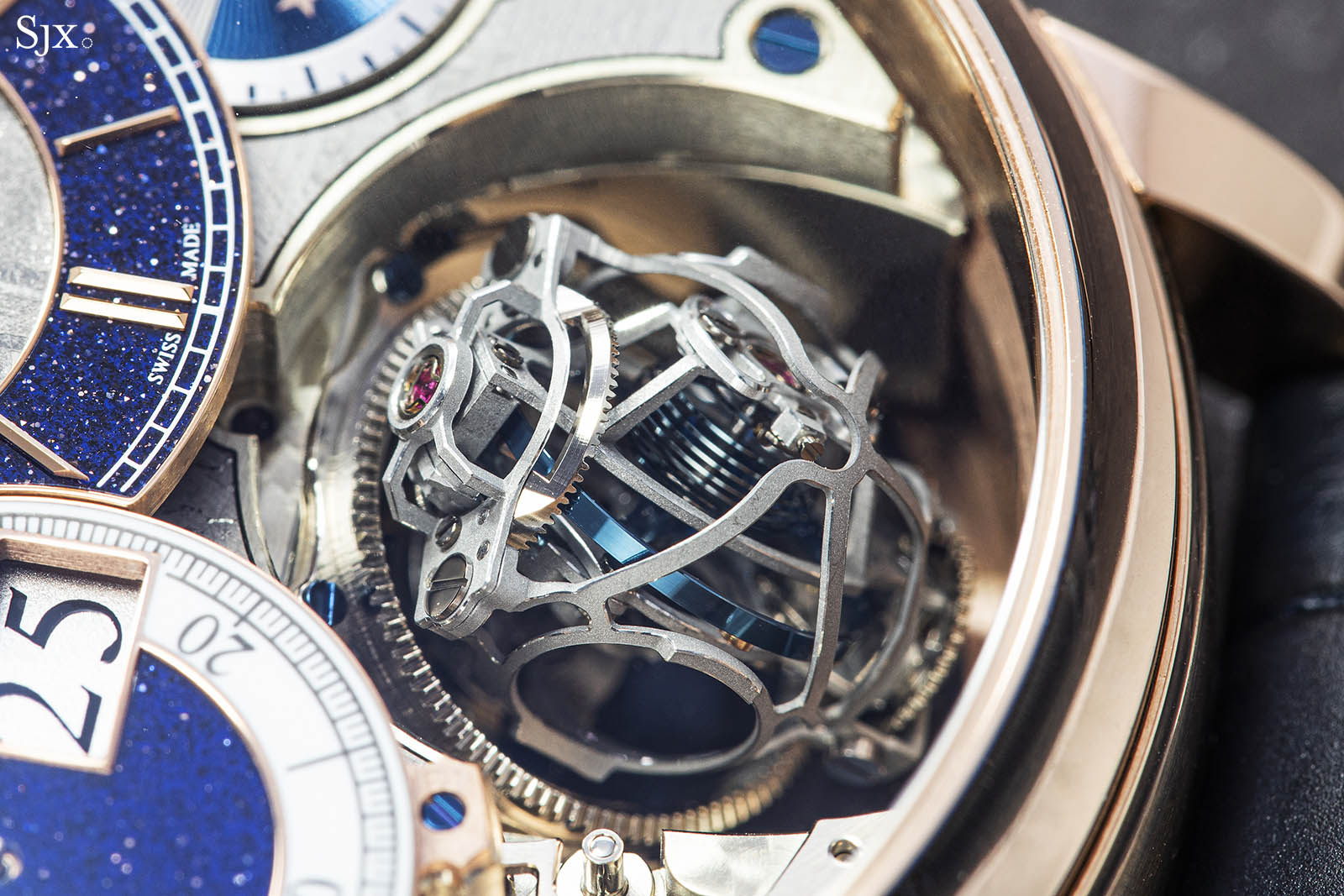

I expected to see Jaeger-LeCoultre in the 30-99 range, but the brand’s production of 95,000 watches per year and headcount around 1,200 suggest a maximum of 20 watchmaker-hours per watch. The brand’s technical know-how is evident in the fact that it is able to produce so many watches with finishing (in its core range) on par with rivals like Glashütte Original, while also producing a wide variety of unusual complications like the Reverso Tribute Gyrotourbillon that clearly benefit from many hours of hand finishing.

When it comes to elaborate and unusual complications, Jaeger-LeCoultre is in a category by itself

Another surprise was Zenith, with a maximum of 29 watchmaker-hours per watch. Zenith tends to compete on price with Rolex and IWC, but the data indicates that about six times as many labour hours are available for the production of each watch compared to these rivals. While Zenith makes excellent watches, it’s hard to see where this extra labor effort is going, leading me to speculate that there is excess capacity in the production process.

Nomos is a standout brand in this category due to its low average price point. Nomos benefits from the same “Glashüttenomics” as Lange and Glashütte Original, with lower labor costs than in neighboring Switzerland. This means the brand can afford to invest more watchmaker-hours in each piece, raising the level of craftsmanship (and also value) compared to similarly priced Swiss rivals.

Industrial prowess: 1-9

Most large luxury watch brands have organised their production processes to spend no more than nine watchmaker-hours per watch. Big names like Rolex, Omega, IWC, Cartier, and Grand Seiko can spend a maximum of 3-6 watchmaker-hours per watch.

In seeking to appeal to a mainstream audience, these brands tend to stick to clearly defined aesthetic codes that have evolved over decades. Whether it’s the Rolex Submariner, Cartier Tank, Omega Speedmaster, or Breitling Navitimer, historical fidelity and unambiguous positioning are key. Prominent brand partnerships and A-list ambassadors maximize mimetic desire.

These brands are able to produce enormous numbers of high-quality watches thanks to investments in state-of-the-art manufacturing facilities, which are at the forefront of automation in the context of watchmaking. While final assembly is largely manual, production, finishing, and testing are done in large batches by primarily automated methods.

But that’s not to say their products are inferior. One of the great contradictions in watchmaking is the fact that industrial brands that make watches with the least amount of human involvement tend to have the most exacting internal requirements for precision, and also the longest warranties.

Testing a batch of 100 watches at Tudor. For context, this tray could hold the total annual production of Kari Voutilainen, Roger Smith, Akrivia, Bexei, and Raul Pages combined. Image – Tudor

In a category filled with brands that make hundreds of thousands of watches per year, Grand Seiko is an outlier, with an annual production around 45,000 watches. Though this volume seems almost artisanal next to a brand like Rolex, Grand Seiko is nonetheless at the forefront of mass production among the brands studied. Assuming a typical statutory work week, Grand Seiko can likely invest no more than 3.8 watchmaker-hours in each watch.

For a true apples-to-apples comparison, I excluded quartz and Spring Drive and focused only on Grand Seiko’s mechanical watch production, referencing Plus9Time’s detailed manufacture visit from 2016 which documented 60 watchmakers producing 30,000 watches annually. While Grand Seiko has recently transitioned its mechanical watch production to a new facility and introduced the new cal. 9SA5, the bulk of the brand’s mechanical watch output by volume consists of the same core movements that were in production in 2016.

Artisan studios

I mentioned that the watchmaker-hours metric is not perfect. One of its inherent problems is the fact that it conflates a brand’s entire production into a single number, obfuscating the differences between a brand’s primary collections and its elite pieces.

This is a problem because many brands effectively operate artisan studios within their manufactures that operate semi-independently and produce watches with very different economics than those of the broader organisation.

The Patek Philippe ref. 5959P exhibits a level of craftsmanship that suggests at least 200 watchmaker-hours per watch, but the brand’s more industrial products make up the bulk of its annual production of over 60,000 watches

Examples include Seiko’s Micro Artist Studio and Montblanc’s Minerva manufacture. For these workshops, I was able to find enough data to segment them as standalone brands in the market map. Unfortunately, the team structures at other brands like Vacheron Constantain and Patek Philippe are not as well-defined and so I was not able to plot these specialist workshops individually. That said, I estimate that over 200 watchmaker-hours are allocated to these brands’ halo pieces, like the Patek Philippe ref. 5959 split-seconds chronograph.

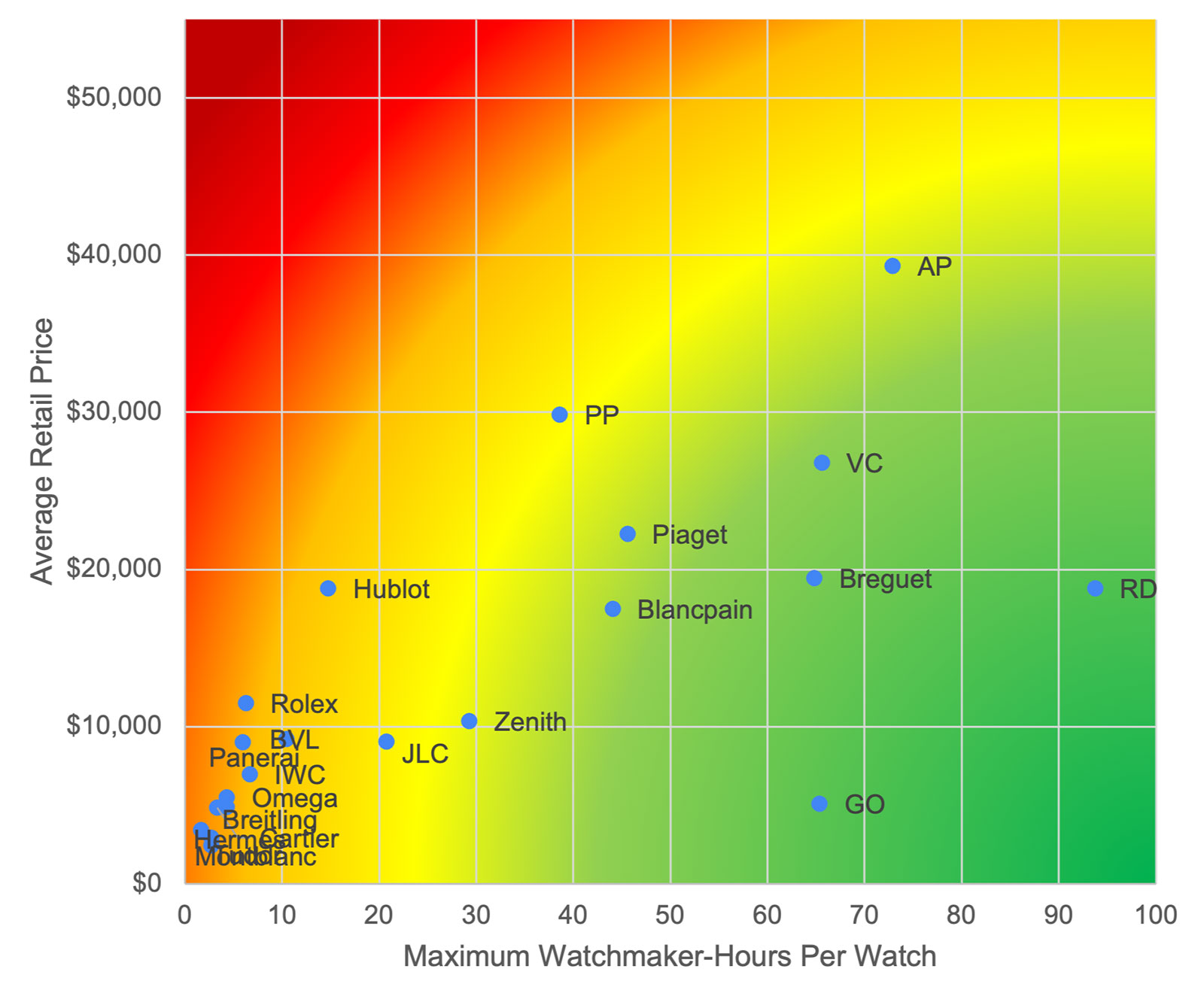

Watchmaker-hours per dollar

The watchmaker-hours metric can also be combined with price data to visualise clusters of brands that offer similar levels of craftsmanship value. This graph helps illustrate which brands have more pricing power in the market and can charge the highest prices on a watchmaker-hour basis.

Glashütte Original is the standout value king, charging a mere US$78 per watchmaker-hour. Comparing the “big three” brands, Patek Philippe’s watches are priced at US$773 per watchmaker-hour, compared to about US$540 for Audemars Piguet and US$408 for Vacheron Constantin. Lange and Journe clock in at US$198 and US$225, respectively.

The closer a brand is to the red zone, the more costly it is on a watchmaker-hour basis

Because of their extreme top-right positions, excluding A. Lange & Söhne and F.P. Journe provides a better look at the lower-left sector.

The same data excluding F.P. Journe and Lange

The price of fame

Though it may seem counter-intuitive, mainstream brands like Rolex, Omega, IWC, Cartier, Breitling, Hermes, and Montblanc all charge more than the haute horlogerie brands on a watchmaker-hours basis. Their average prices are much lower, but their extreme production efficiency results in watches that cost more than US$1,000 per watchmaker-hour.

Watchmaker-hours throughout history

These numbers take on additional meaning when put into historical context.

According to data compiled by Professor Pierre-Yves Donzé, Louis Brandt & Frère produced 100,000 pocket watches with 600 staff in 1890. Assuming 12-hour workdays (working hours were much longer back then), this works out to a maximum of around 17 watchmaker-hours per watch. This is similar to rival Longines, which could invest a maximum of 20 watchmaker-hours per watch in 1901, and 19 watchmaker-hours in 1905.

By 1914, Louis Brandt & Frère had been renamed Omega (in honour of its flagship pocket watch movement) and reduced its maximum watchmaker-hours per watch to about 12, with 935 staff producing an estimated 235,000 watches annually.

However, neither Omega nor Longines could match the production efficiency of Tavannes, which imported American watchmaking equipment and, by 1913, was able to produce 2.6 watches per watchmaker per day, suggesting a maximum of around five watchmaker-hours per watch.

Today, thanks to modern advances in computer-aided design and manufacture, makers of mainstream luxury watches are able to produce millions of watches annually with just a few watchmaker-hours per watch, while offering significantly improved precision and durability.

The movement assembly workshop at IWC that is representative of large-scale watchmaking in the modern day. Image – IWC

Observations

Viewed through the lens of watchmaker-hours, the industry comes into focus. Previously ill-defined categories like “independents” and haute horlogerie can now be defined more objectively, with lines drawn according to quantifiable dimensions.

While I believe there’s a limit to the utility of thinking about solely about brands – in fact I encourage collectors to judge each watch on its own merits – I do think a market map can be helpful for visualising clusters of brands to calibrate expectations about their products. This is especially the case for new enthusiasts, but it can also be a helpful sanity check for even the most seasoned collectors.

This map highlights the massive differences in unit economics between the large and small brands, and illustrates the thresholds at which different levels of craftsmanship are possible. It also reveals the differing nature of exclusivity across the industry. Some of the brands most coveted for exclusivity, like Patek Philippe and Rolex, have been able to maintain this image despite their large production due to the fact that select models remain in short supply.

In contrast, watches from brands towards the top of the table are inherently more exclusive by nature of their production methods, which limit the number of watches that can be produced to just a few pieces each year.

Rexhep Rexhepi of Akrivia, which produces less than 30 watches a year

The map also highlights another important point. If a brand’s watchmaker-hours count is surprisingly low, it means that either less time is spent on hand craftsmanship, or more work is done by third-parties than is disclosed.

While it’s tempting to view each segment as homogeneous, there is still room for substantial differentiation within each tier. Not all brands have access to the same capital, intellectual property, or expertise. The industrial know-how of some brands means they’re able to accomplish a lot more with each watchmaker-hour.

This is especially true towards the bottom of the pyramid where watches receive less human involvement; when a watch is made substantially by machines, the differentiated capabilities of those machines really matter.

For example, Tudor has benefited tremendously from the industrial expertise of its parent company, Rolex. Once a sub-brand that relied on third-party movements, Tudor now punches well above its weight and offers higher quality than brands like Breitling and Panerai, despite a lower average price point.

A final observation is simply the overwhelming size of the larger brands. Cumulatively, the 50-plus brands analysed produce about 3.75 million watches per year with a maximum of about 34 million watchmaker-hours (averaging about nine watchmaker-hours per watch). But at the highest level, brands like Greubel Forsey, Roger Smith, and Bexei are able to spend more that 1,500 watchmaker-hours per watch, raising the median for this sample to around 75 watchmaker-hours.

Data Methodology

- For production and average retail price figures, I relied on the 2022 watch industry report by Morgan Stanley and LuxeConsult, data provided by brands, and published interviews with brand executives.

- For headcount data, I relied on data provided by brands, published interviews, and firsthand reports from manufacture visits. Where no data could be found, I used my own estimates.

- Brands are arranged by estimated annual production volume from high to low within each segment.

- Since not all employees are watchmakers, the model assumes that 85% of total employees are production watchmakers (a generous assumption). In cases where the true number of watchmakers is known, this adjustment was not made.